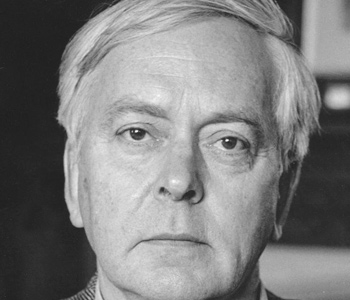

Peter Laufer

Calexico: True Lives of the Borderlands

University of Arizona Press

213 pages, 6 x 9 inches

ISBN 978 0816529513

Calexico takes the reader to a border unlike the stereotypes.

The lawlessness of some border flashpoints dominates border news. The bulk of Americans, those of us living far from the 2,000 miles of border, conjure up drugs into San Diego and illegal immigration into El Paso when considering that frontier, or murders in Juarez and slums in Tijuana.

But Tijuana-San Diego and Juarez-El Paso are not the only examples of the Mexican border.

On my last trip to the border I headquartered myself far from the urban crossroads. I chose sleepy Calexico.

I hung out with the locals, Calexicans who live a bi-lingual, bi-cultural life. Their day-to-day existences and their futures depend on their relationships across the artificial line in the sand with Mexicali.

Most Americans agree the border is broken. By studying the unique Borderlands culture through the lens of Calexico we may well find fixes that elude the policymakers in Washington and Mexico City.

After September 11, 2001, Washington decided that one of the answers to threats of terrorism was to detain travelers driving north at the Mexican border and relentlessly question them.

What the lawmakers and bureaucrats back east did not take into account was that extended communities straddle the border at places like the twin cities of Calexico and Mexicali.

The new rules slowed traffic, increased smog, burned up expensive gasoline and—according to Calexicans like Chamber of Commerce president Earl Roberts—created the absurd scenario of border guards who know travelers intimately and have known them all their lives asking questions such as “What’s you name?” and “Where do you live?”

Earl Roberts and the Chamber responded with their “Efficiency is Security” campaign. They’re trying to teach Washington that citizens who live in the borderlands know best how to manage traffic from Mexico and should be consulted before policies are changed, especially policies that can adversely affect the borderlands.

The longer waits at the border dissuade Mexican shoppers from traveling north, a disaster for Calexico retailers who rely on consumers from south of the border. And there is little evidence that the detailed questioning results in protecting the homeland from terrorist attacks.

Especially in this post-September-11 environment, fear overtakes reality. But even before the attacks of ten years ago, the tendency of too many Americans was to succumb to xenophobia and try to pull up the drawbridge.

We’ve always suffered from an immigration hierarchy in this country. My father came here from Europe during the Great Migration era when the Hungarians were the Mexicans of the times. His sister married a man from Shanghai. In the 1950s, when their son, my cousin, was growing up, teasing him was easy: if his classmates weren’t calling him a Hunky they were calling him a Chink.

The prejudice against Mexicans is exacerbated by geography. The border between Mexico and the States is the only place on the globe where the First World and Third World meet. Americans can look south—can easily travel south—see the economic disparities and say to themselves, “I don’t want my backyard to look like that.”

But I think the sad major reason why there is no serious policy consideration to open the border to Mexicans is because of the jingoistic fear-mongers, well personified by Lou Dobbs, who successfully, and for their self-aggrandizement, generate and perpetuate a climate of anxiety, paranoia, and panic regarding migration from Mexico.

I cannot pick out a single page where I would want your browsing reader to go first.

One of the joys for me of this project is that the book is packed, page after page with surprises and luring text. Whether it is my encounter with Geraldo Rivera about Lou Dobbs, or my musings with Rod McKuen about the similarities of the Vietnam Era and current times, or my reverie with the Miller Lite marketer about capitalism transcending the political border, the book is alive with the remarkable philosophizing that comprises true lives of the borderlands.

My hope is that Calexico is another step toward ending the demonization of migrants from Mexico by the xenophobic demagogues who capture so much attention in today’s over-mediated news landscapes.

We need to appreciate the new immigrants join our nation of immigrants.

The most important economic gain of opening the border is the neutralizing of illegal border crossings by otherwise law-abiding Mexicans and hence freeing up the overworked Border Patrol to stop those we do not want entering America.

Immigration fuels our economy. We are an aging society with a low birth rate. If we welcome workers from Mexico who need not fear persecution and prosecution in their daily lives, they will engage our economy on multiple levels that they fear to do while undocumented. They will buy more goods and services. They will not feel forced to hide in jobs that offer minimal employment opportunities but will feel free to improve their working conditions. This will result in more disposable income and provide the opportunity for the culture to reap greater good from their talents and efforts. More border dwellers will spend their pesos in Gringolandia and tourist traffic from south to north will increase.

And consider the political gains: Just putting the Mexicans-Go-Home nativist U.S. politicians out of business is good enough.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!