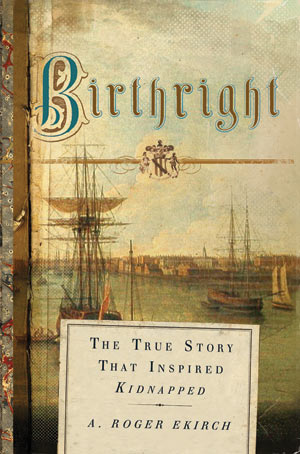

Birthright sets out to recount, for the first time, the real-life saga of James Annesley, which not only captivated eighteenth-century Britain but inspired five novels, most famously Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic adventure tale, Kidnapped.In 1728, at twelve years of age, “Jemmy” was kidnapped from Dublin and shipped by his uncle to America as an indentured servant. Uncle Richard, his blood rival, usurped the boy’s inheritance of five aristocratic titles belonging to the mighty house of Annesley, together with sprawling estates in Ireland, England, and Wales. Only after twelve more years, in the backwoods of northern Delaware, did James successfully escape to Jamaica, then to England, and, finally, to Ireland, where he set about reclaiming his birthright, all the while defying accusations of being a “pretender,” the bastard son of a maidservant, in addition to repeated attempts on his life.How, after such a long absence, in an age without DNA laboratories, fingerprint records, or photographs could an impoverished prodigal prove his identity, let alone his legitimacy? At stake during the epic trial held in Dublin in 1743—the longest in memory—was the greatest family estate ever put before a jury. Still, the trial was just the beginning of a tortuous quest on the road to redemption. Bursting with an improbable cast of characters, from a brave Dublin butcher and a wily Scot to the king of England, Birthright evokes the volatile world of Georgian Ireland—complete with its violence, debauchery, ancient rituals, and tenacious loyalties.With any luck, readers will find this family drama as engrossing as I have over the course of six years of research and writing. It is an astonishing story to which I hope that I have done justice.