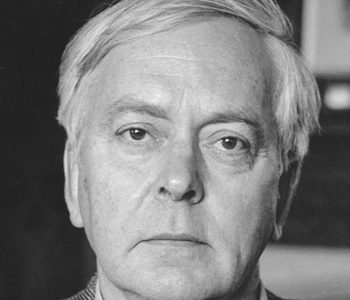

W. G. (Garry) Runciman has been a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge since 1971. He holds honorary degrees from the Universities of Edinburgh, London, Oxford, and York. He is a Fellow of the British Academy and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Besides Great Books, Bad Arguments, featured in his Rorotoko interview, his other books include A Treatise on Social Theory, The Social Animal, and The Theory of Social and Cultural Selection.

Great Books, Bad Arguments looks at three of the most famous texts in Western political thought and asks whether the proposals advanced by Plato, Hobbes, and Marx for the avoidance of disorder and injustice in human societies are sufficiently plausible, when analyzed sociologically, to carry conviction.The conclusion I draw is that they are not. And that the problem which they accordingly pose is that of accounting for their enduring reputation as ‘great books.’My suggested answer is that they should be read as masterpieces of what I call ‘optative’ sociology. By that I mean that Plato, Hobbes, and Marx want their readers to share not only their anger and dismay at what they see in the world around them but their passionate hope that a way can somehow be found to bring into being institutional arrangements whereby human beings can live together in harmony.Many other commentators have pointed out what they see as weaknesses in Plato’s, Hobbes’s, and Marx’s arguments for their respective proposals. But none has gone on to account for how it is that proposals so demonstrably unrealistic can continue to command such universal and admiring attention.

W. G. Runciman Great Books, Bad Arguments: Republic, Leviathan, & The Communist Manifesto Princeton University Press138 pages, 8 x 5 inches ISBN 978 0691144764

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!