Jonathan Gottschall

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

272 pages, 5 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches

ISBN 978 0547391403

You might not realize it, but you are a creature of an imaginative realm called Storyland. Storyland is your home and before you die you will spend decades there. If you haven’t noticed this before, don’t feel bad: story is for a human as water is for a fish—all encompassing and not quite palpable. While your body is always stuck at a particular point in space-time, your mind is always free to ramble in lands of make-believe. And it does.

We read novels. We go to movies. We watch TV serials, and the faux non-fiction of reality shows and pro wrestling. We groove to ultra-short fictions in popular songs. We lose ourselves in video games that make us the rock-jawed heroes of action films (or fleshed-out characters in story-rich games like The World of Warcraft).

When we are not consuming stories made up by others, we are making up our own. Our children play at story by instinct—inventing scenarios and acting them out in Neverland. When our bodies sleep, our restless minds stay awake all night telling fevered stories. And we don’t stop dreaming when the sun comes up. We spend hours per day spontaneously generating daydreams in which all of our vain, dirty wishes—and all of our secret fears—come true.

Scientists and philosophers have long debated the human essence—the thing that sets us apart most fundamentally from the rest of creation. Is it intelligence (Homo sapiens)? Is it the sophistication of tool use (Homo habilis)? Is it upright posture (Homo erectus)? Is it playfulness (Homo ludens)? Or could it be language or the complexity of our social behavior? These factors are all important, but an equally important factor has been overlooked. Big brains and upright posture set us apart—so does the way we live in Storyland. I give you Homo fictus (fiction man), the great ape with the storytelling mind.

My career has focused on bridging the gap between the estranged cultures of the humanities and sciences. How can we use science to better understand fiction? And what can scientists learn from fiction and the other arts?

But the idea for this book came to me not from research but from songs.

One day, I was at the gym, gerbilling away on the treadmill and channel surfing. Suddenly Billie Ray Cyrus was staring at me with his highlighted bangs hooking down over his eyes. For some reason I didn’t turn the channel. Instead, I listened to Billie Ray sing a song about his daughter Miley, and the way she was growing up and moving on. He reached the chorus—“Baby, get ready, get set…please, don’t go”—and the tears crowded into my eyes and spilled down. I mopped my face with my towel, pretending it was sweat. Gnawing my unsteady lips, I turned the channel.

Weeks later, I was driving down the highway and happened to hear the country music artist Chuck Wicks sing a similar song about a little girl growing up to leave her father behind. For some reason I didn’t turn the channel. Before I knew it, I was blind from tears. I had to veer off on the side of the road to get control of myself and to mourn the time—still well more than a decade off—when my own little girls would fly the nest. I sat there on the side of the road feeling sheepish and wondering, “What just happened?”

Who hasn’t had a similar experience? When we submit to fiction—whether in novels, songs, or films—we allow ourselves to be invaded by storytellers who seize control of us cognitively and emotionally.

I wanted to understand how stories—the fake struggles of fake people—could have such power over us. The Storytelling Animal is about the way explorers from the sciences and humanities are using new tools, new ways of thinking, to open up the vast terra incognita of Storyland. The book is about the way that stories—from TV commercials to daydreams to religious myths—saturate our lives. It’s about deep patterns in the happy mayhem of children’s make-believe, and what they tell us about story’s prehistoric origins. It’s about how fiction subtly shapes our beliefs, behaviors, ethics—how it powerfully modifies culture and history. It’s about the ancient riddle of the psychotically creative night stories we call dreams. It’s about how a set of brain circuits—usually brilliant, sometimes buffoonish—force narrative structure on the chaos of our lives. It’s also about fiction’s uncertain present and hopeful future.

Above all, The Storytelling Animal is about the deep mysteriousness of story. Why are humans addicted to Storyland? How did we become the storytelling animal?

To see what a hard question this is, let’s conduct a fanciful, but hopefully illuminating, thought experiment. Throw your mind back into the mists of prehistory. Imagine that there are just two human tribes living side by side in some African valley. They are competing for the same finite resources: one tribe will gradually die off, and the other will inherit the earth. One tribe is called the Practical People and one is called the Story People. The tribes are equal in every way, except in the way indicated by their names.

Most of the Story People’s activities make obvious biological sense. They work. They hunt. They gather. They seek out mates, then jealously guard them. They foster their young. They make alliances and work their way up dominance hierarchies. Like most hunter-gatherers they have a surprising amount of leisure time, which they fill with rest, gossip, and stories—stories that whisk them away and fill them with delight.

Like the Story People, the Practical People work to fill their bellies, win mates, and raise children. But when the Story People go back to the village to concoct crazy lies about fake people and fake events, the Practical People just keep on working. They hunt more. They gather more. They woo more. And when they just can’t work anymore, the Practical People don’t waste their time on stories: they lie down and rest, restoring their energies for useful activity.

Of course, we know how this story ends. The Story People prevailed. The Story People are us.

If those strictly practical people ever existed, they don’t anymore. But if we hadn’t known this from the start, wouldn’t most of us have bet otherwise? Wouldn’t we have bet on the Practical People outlasting those frivolous Story People?

The fact that they didn’t is the riddle of fiction. Evolution is ruthlessly utilitarian. How has the time-gobbling luxury of fiction not been eliminated from the human repertoire?

In short, no one knows for sure.

But researchers are converging on a possible solution. Drawing on research in dreams, pretend play, and world fiction, I explore the possibility that stories are the flight simulators of human life. Fiction projects us into intense simulations of problems that parallel what we face in reality. And, like that of a flight simulator, the main virtue of fiction is that we have a rich experience and don’t die at the end. We get to simulate what it would be like to confront a dangerous man or seduce someone’s spouse, for instance, and the hero of the story dies in our stead.

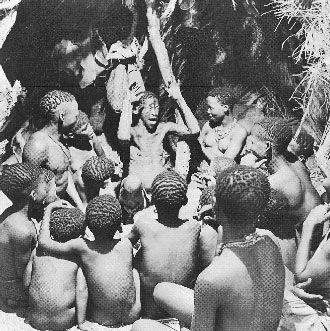

Kung San Storyteller. 1947. Photograph by Nat Farbman.

This book uses insights from biology, psychology, and neuroscience to try to understand the storytelling instinct. I am aware that the very idea of bringing science—with its sleek machines, its cold statistics, its unlovely jargon—into Storyland makes many people nervous. Fictions, fantasies, dreams—these are, to the humanistic imagination, a kind of sacred preserve. They are the last bastion of magic. They are the one place where science cannot—should not—penetrate, reducing ancient mysteries to electro-chemical storms in the brain or the timeless warfare among selfish genes. The fear is that if you explain the power of Neverland, you may end up explaining it away. As Wordsworth said, you have to murder in order to dissect.

But I disagree. Science adds to wonder, it doesn’t dissolve it. Scientists always report that the more they discover, the more lovely and mysterious things become. As the great novelist and distinguished lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov once put it, “The greater one’s science, the deeper the sense of mystery.” That’s certainly what I found in my own research. The whole experience left me in awe of Homo fictus—the beast who lives in fiction.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!