Belmonte , Laura

Selling the American Way: U.S. Propaganda and the Cold War

University of Pennsylvania Press

272 pages, 6 x 9 inches

ISBN 978 0812240825

Selling the American Way is about the ways that the U.S. government defined and disseminated official narratives about American society, politics, and culture during the early Cold War. Using radio programs, printed materials, films, music, art, sports, and other means, the State Department and the United States Information Agency sought to persuade foreign audiences to embrace democratic capitalism and to reject communism. The book’s first two chapters detail the political context in which these peacetime propaganda activities evolved and explain why it was often quite controversial for a democracy to engage in these activities. Heated political battles arose about the possible ramifications of targeting foreign audiences. Would, for example, a mass exodus of refugees from behind the Iron Curtain, overwhelm relief agencies? Would a U.S. propaganda offensive trigger a popular uprising that necessitated a U.S. military response? What, exactly, defined “the American way of life”? Such questions bedeviled U.S. policy makers, information experts, and congressional representatives.

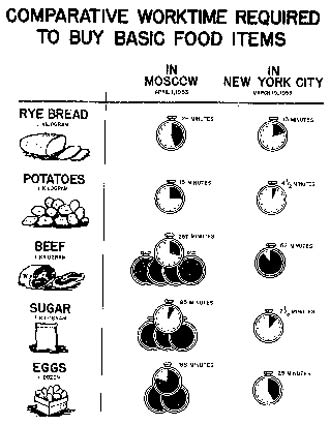

The book’s next four chapters examine how specific elements of American life (politics, consumerism, labor, gender and the family, race, and religion among others) were “packaged” for international audiences. I discuss how the hallmarks of democracy and capitalism were explained and why and how foreign audiences did not passively or completely accept the visions of the United States being propagated abroad. Foreign audiences instead adopted a selective approach to what they admired and what they found hypocritical or contradictory. While it may have been easy for international audiences to grasp the allures of the U.S. standard of living as juxtaposed to life in a Soviet labor camp, they proved much more skeptical about declarations that the United States was actively combating racism and segregation.

Selling the American Way is written to be accessible to readers of serious nonfiction. I have intentionally avoided freighting the book with jargon and have situated these Cold War-era propaganda campaigns within the context of post-9/11 America. Accordingly, I hope the book will be both relevant and enjoyable.

Propaganda campaign, no matter how well-crafted or thoughtful, will have its desired effect if the United States simultaneously contradicts its professed values, both at home and abroad.

I began researching Selling the American Way in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. I was very interested in determining how foreign audiences understood the United States and its people – and what role, if any, international perceptions of democratic capitalism had in triggering the collapse of communism. Because I am a diplomatic historian, I am also fascinated by how U.S. policy makers translate and use power. But I didn’t want to focus on traditional forms of power such as military or economic power. At the time, there were also a number of exciting new works appearing in U.S. foreign relations scholarship that were considering the role of social and cultural factors in American foreign policy. Scholars were examining issues like religion, gender, culture, rhetoric, emotion, and race.

After months of reading both primary and secondary sources, I concluded that an examination of the context, content, and reception of U.S. propaganda provided a wonderful way to address questions about the evolution and outcome of the Cold War’s ideological war – and also enabled me to deploy and expand some of this exciting new work in diplomatic history.

The project took longer than I expected. Thanks to a major declassification effort by the Clinton administration and 9/11, literally thousands of radio transcripts, internal documents, films, country plans, and other materials became accessible to scholars for the first time. I conducted research for almost four additional years. I should add that the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 had precluded American citizens from reading, seeing, or listening to the propaganda materials the U.S. government disseminated abroad. That legislation created some interesting challenges at the archives of the United States Information Agency. I was allowed to take notes on, but not photocopy, propaganda pamphlets from the 1940s and 1950s. It is hard to believe these restrictions are still in effect.

Then, the 9/11 attacks shattered the remnants of the containment doctrine and facilitated the implementation of entirely new paradigm, the Bush Doctrine. Those events forced me to reframe my arguments. Amidst the simplistic hand-wringing decrying “why they hate us,” I saw striking parallels to the ways American officials were characterizing “terrorists” and the ways that they had defined “communists.” I also saw important connections between how notions of “freedom” were being deployed in the post-9/11 era and the early Cold War years. I believe that a careful study of the uses and construction of propaganda in the earlier period illuminates why public diplomacy remains a very important, though highly underutilized, element of U.S. foreign policy. But we must remain vigilant to the reality that no propaganda campaign, no matter how well-crafted or thoughtful, will have its desired effect if the United States simultaneously contradicts its professed values, both at home and abroad.

U.S. information experts drew stark contrasts between the lives of American and Soviet workers. This chart, prepared for the USIA by the U.S. Department of Labor, explained purchasing power in terms average people could understand. (Photo courtesy of National Archives; appears in the book on page 130.)

Start with the introduction to see how and why I situate the early Cold War propaganda campaigns into a post-9/11 context. I think anyone who has noted contemporary discussions about American “soft power” and the occasionally bombastic rhetoric about people hating “our freedoms” will be intrigued by the ways that the early Cold War informs these more recent trends. I also believe people concerned about the U.S. role in the world will be interested in learning more about how scholars are now approaching the study of U.S. foreign relations.

If the reader survives the introduction, then I’d direct him or her to one of the four “topical” chapters addressing how features of American life were explained and received. Each chapter is filled with wonderful tidbits about how U.S. policy makers made things as diverse as refrigerators, Sears’ catalogues, Monopoly games, jazz, and voting booths tools in their effort to persuade foreigners to emulate “the American way of life.” We also see how, time and time again, international audiences, honed in on weaknesses in U.S. society, forcing U.S. information experts not only to revise their tactics and materials, but also to reevaluate their understandings of what it means to be “American.”

There are some fascinating vignettes that demonstrate these trends. Depictions of race relations were particularly tricky. For example, at the American National Exhibition in Moscow in July 1959 (site of the famous “kitchen debate” between Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev), U.S. information experts originally included an interracial couple in a bridal show designed to highlight American fashion and family mores. But, when foreign journalists saw a preview of the show and lambasted USIA for its unrealistic reflection of racial realities, U.S. officials replaced the couple with a white bride and groom. International audiences aware of lynchings, the furor attending the integration of public schools, and U.S. laws precluding interracial marriage were justifiably very skeptical about propagandists’ assertions that America was making great strides toward racial equality.

But, at the same time, the unpredictability of audience reactions also flummoxed communist propagandists. Over 3 million Soviets attended the Moscow exhibition. Neither years of anti-capitalist rhetoric nor limited exposure to non-communist life prevented these visitors from quickly grasping the attractions of American consumerism – literally. People stole books, toys, even frozen food samples, in their eagerness to have tangible reminders of the bounties of “decadent capitalism.”

The Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 had precluded American citizens from reading, seeing, or listening to the propaganda materials the U.S. government disseminated abroad. That legislation created some interesting challenges at the archives of the United States Information Agency. I was allowed to take notes on, but not photocopy, propaganda pamphlets from the 1940s and 1950s.

I hope that Selling the American Way will prompt readers to be more attuned to how U.S. policy makers explain and have explained our nation and its international role to the world – and that we as informed citizens then demand that they address the often yawning gap between who we say we are and how we actually act in the global realm. Propaganda, public diplomacy, information, soft power – whatever euphemism one chooses – cannot alone ensure U.S. national security. But it most definitely can – and has – contributed to a better understanding among the world’s peoples, an objective I believe is more important than ever.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!