Göring’s Man in Paris is about three things: first, it is a detailed portrait of a Nazi art plunderer (Dr. Bruno Lohse); second, it tells the story of what happened to Lohse and his associates after the war; and third, it’s about the relationship that developed over a nearly ten-year period between Lohse and the author.

In terms of the first, the book provides a close and personal perspective of a Nazi art plunderer. It takes the reader into Bruno Lohse’s world of Nazi thievery—from his heyday as “king of Paris”, to his capture, imprisonment, and rehabilitation. During the war, Lohse boasted that he killed Jews with his own hands, and while this is unconfirmed, it is known that Lohse regularly joined in on the commandos’ raids of the homes of French Jews. Sometimes these domiciles were still “warm”, the Jewish residents having just recently been evicted, which shows how plundering was inextricably linked to the Holocaust. It also highlights the moral complexities of history, as Lohse was able to protect some Jews (mostly those who helped him), and he also played a key role in saving Neuschwanstein Castle that contained tens of thousands of looted artworks when rogue SS units roaming the south German countryside at war’s end threatened to blow up the castle and its contents.

The second main contribution of the book is that it takes the story of Nazi art plundering into the postwar world. Once the judicial trials and denazification process were completed by 1950, the paper trail in the archives ends. For this part of the history, I was able to interview Lohse and other Nazi plunderers, as well as their friends, and I had access to many of Lohse’s own papers, which allowed me to write about the postwar period. What is most stunning is the degree to which Bruno Lohse revived his career after 1950: he formed a friendship with Theodore Rousseau, a former OSS officer who became the chief curator for European paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He consorted with the elite of the art world. Perhaps most remarkable, he became an associate of the Wildensteins—the French-American Jewish family that rose to become arguably the greatest art dealers in the second half of the twentieth century. The complicated relationship between Lohse and the Wildensteins is the subject of the last chapter of the book.

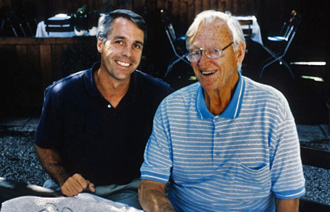

Third, in the epilogue, I detail my experiences interviewing old Nazis, and Bruno Lohse in particular. Over a nine-year period, I met with Lohse dozens of times and pressed him on questions about the fate of missing artworks such as the “Fischer Pissarro” (one of the last paintings by the French Impressionist that was once owned by members of the famous publishing dynasty, the Fischer family). Lohse and I played a cat and mouse game, but I eventually discovered some of Lohse’s secrets, including his keeping the looted Fischer Pissarro in a Zurich bank vault, along with other stolen artworks (the Fischer Pissarro was eventually restituted to the heirs). Göring’s Man in Paris shows the challenges and pitfalls of interacting with an old Nazi like Bruno Lohse.

Göring’s Man in Paris is about the art world, and how profit is such a driving force that one of the greatest art plunderers of all time could insinuate himself in the respectable art world just months after being released from a French prison. The art world is secretive, as was the world of former Nazi art plunderers. It took over thirty years of research to write this book, and it was the interviews with Lohse and other figures in his circles that allowed me to understand the complex networks that he helped sustain.

The center of the networks was in Munich, the birthplace of the Nazi movement. After 1945, many old Nazis settled there, including in the areas around Lake Starnberg to the southwest of the city. Individuals in the states contiguous to Bavaria (of which Munich is the capital) played a key role in these networks. It included some in Austria (which also had many former Nazis), Switzerland (with its secretive banking culture), and Liechtenstein (which featured foundations created to evade taxes). The networks extended to other parts of Europe and to the United States. The U.S. was the most important market in the art world, and it is axiomatic that art follows money. Over 90 percent of museums in the US today were founded after 1945. Lohse and his cohort helped build their collections.

For a closer look, I would direct the reader to the section on the relationship between Theodore (“Ted”) Rousseau and Bruno Lohse. Rousseau, the former OSS officer who interrogated Lohse for several months in the summer of 1945, continued to stay in touch with the Nazi plunderer, despite the fact that Rousseau became a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and later, Deputy Director under Thomas Hoving. I don’t know what is more extraordinary: their relationship, or the fact that Rousseau kept so many of Lohse’s letters in his files. Their correspondence is in the Met Archives and was made accessible to researchers in around 2015, although some of Rousseau’s papers remain closed until 2050 and beyond.

The letters between Ted Rousseau and Bruno Lohse show the two men trading information about artworks for sale. The letters also attest to many visits: Lohse coming to New York to see Rousseau, his former captor, at the Met, and Rousseau meeting Lohse not just in Munich, but also in Paris and Zurich, among other locales. Lohse offered Rousseau many fine paintings by the likes of Botticelli, Monet, and Cezanne, but there is no evidence of the Met acquiring works from him. The question remains: did the former Nazi plunderer use cut-outs (intermediaries who obscured his role), as he did in other instances, including selling two pictures attributed to Albrecht Dürer to the German Historical Museum in Berlin in the early 2000s? Years earlier, Lohse had bragged in one letter to Rousseau from 1959 that he was very successful selling to other American museums, yet he intentionally tried to cover his tracks, and there is a great deal he successfully concealed.

Ted Rousseau was a swashbuckling curator: he was sophisticated (educated at Eton, Harvard, and the Sorbonne), spoke many languages, and was a spy in the Far East before joining the OSS’s Art Looting Investigation Unit. Rousseau was competitive and took chances (his regard for European export laws was notoriously suspect), so it is not surprising that he would turn to a Nazi art plunderer as a source of information and perhaps artworks themselves. There is no doubt that Rousseau understood that a large number of Nazi looted artworks had never been restituted, and he knew exactly who Lohse was, having helped pen the OSS reports on him. But Rousseau wanted to build the Met’s collections and if Lohse could be helpful…

I think the book has many implications—about the nature of the art world, about the nexus of culture and barbarism (the Nazis devoted so much time to art and yet murdered systematically), and about the fate of Nazi looted artworks after the war; but the point I would emphasize here is that there is still so much to uncover. History is accretional, and while I have made my contribution here, I look forward to others continuing to add to the story.

To begin writing this story, it was important that I go and meet Bruno Lohse in 1998, and that I continued to interview him right up until his death in March 2007. Lohse agreed to meet with me for a number of reasons. I had done a Ph.D. at Harvard University and had come to know two of the other OSS officers who had interrogated Lohse at war’s end (Rousseau died in 1973 and I never met him). The two OSS officers had also attended Harvard and Lohse held them (and the university) in particularly high regard. The fact that I could speak and correspond with him in German was critical. Over the years, Lohse became more relaxed and expansive when telling his stories, and these stories served as one of the pillars of this book. I could check them against the extant documentation and talk to those in his circle in order to form a picture of his postwar career.

Lohse sold valuable paintings to museums in Germany, Switzerland, and the United States. In the last years of his life, around 48 pictures that he owned, including works by Monet, Renoir, Nolde, and Albrecht Dürer, were found. These works were worth millions of dollars. How he became such a wealthy individual and established networks that spanned Western Europe and North America is a big part of this story.

I don’t have all the answers, but I think I was able to frame the story and fill in some of the gaps. There is still more work to be done.

Jonathan Petropoulos is the John V. Croul Professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College in Southern California. He began working on the subject of Nazi art looting and restitution in 1983 and received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1990; he also had an appointment as Lecturer in History and History & Literature at Harvard. He is the author of Art as Politics in the Third Reich (University of North Carolina Press, 1996); The Faustian Bargain (Oxford University Press, 2000); Royals and the Reich (Oxford University Press, 2006); Artists Under Hitler (Yale University Press, 2014), and has helped edit a number of other volumes. From 1998 to 2000, he served as Research Director for Art and Cultural Property on the Presidential Commission on Holocaust Assets in the United States, where he helped draft the report, Restitution and Plunder (2001). He has also served as an expert witness in a number of cases where Holocaust victims have tried to recover lost artworks, including Altmann v. Austria, which involved six paintings by Gustav Klimt claimed by Maria Altmann and other family members; five paintings were returned.