A Synthesizing Mind is my intellectual memoir. It’s a ‘memoir’ in the sense that I reflect on my life; it’s ‘intellectual’ in that it focuses chiefly on my life as a student, researcher, writer, mentor, and teacher. But there’s plenty on my own personal development as well. Starting with the intellectual: Ever since I can remember, I have been fascinated by the human mind. Indeed, over half of my many books contain the word ‘mind’ in the title. But until recently, I have focused on ‘minds’ in general or on the minds of other persons—young children, students, political leaders, creative geniuses in the arts and sciences, etc. In this book, in contrast, I focus on my own mind—which I conclude is a synthesizing mind. More on that later.

Back to my life. I begin with an account of growing up in Scranton, Pennsylvania at the same time as Joe Biden—in fact we are the same age. I describe the many influences on my early life—my Jewish parents escaping from Nazi Germany in the nick of time, arriving in New York City with only $5 in their pockets; the death of my (highly gifted) only sibling, when my mother was pregnant with me, and the resultant feeling that I was a ‘replacement child’—indeed, for a while, according to them, the only entity that kept my parents alive.

In those early days, I acquired my love of music, my fascination with the written word, and various compensations for a potpourri of visual problems. I speculate about the sources of my most enduring intellectual interests, as well as my critical attitude toward psychological tests. I describe valued mentors, as well as tormentors and anti-mentors. Most important, I detail how I became fascinated by the human mind—to whose study I’ve devoted my scholarly life.

Why, nearing my 9th decade, did I feel the need to understand my own mind? Because I realized that my theory of ‘multiple intelligences’—for which I am best known—does not explain well my own ways of thinking and performing. I am, and since early childhood have been, a synthesizer. I read (and observe and converse) widely; I reflect on this information and try to ‘connect’ the dots; I discover new questions and ideas, and try to integrate them with one another and with what I had earlier thought. I arrive at a major question or project and bring all of that accumulated information to bear on it. I organize and re-organize that information multiple times. I try out the tentative syntheses on friends and friendly critics. And at last, I go public, typically in a book form—though I have also written hundreds of blogs and well over 1000 scholarly and more popular articles.

So that’s my synthesizing mind. But I agree with the Nobel Laureate in Physics Murray Gell-Mann, who once said: “In the 21st century, the most important kind of mind will be the synthesizing mind.” In the memoir, I describe how that mind works. But I also claim that psychology has largely dropped the ball on how synthesizing operates; and that’s because it’s too unwieldly a capacity to simulate in a laboratory experiment or to probe via a short answer test. Accordingly, in the concluding chapters, I offer my own primer on how to develop and educate a synthesizing mind.

In recent years, especially in the United States, our schools have focused largely on the mastery of information, which can be probed in a short answer assessment. This is exactly the kind of information which is readily available on search engines or can be instantly computed on an inexpensive handheld device.

Except in select educational institutions—typically ones available only to privileged families—there is little effort to train synthesizing, or even to put it on the map as an important educational goal. From my perspective, genuine synthesis begins with an important issue or puzzle that one wants to elucidate. Of course, one should first ascertain what already exists on the topic—and if the available synthesis seems adequate, move on to another puzzle.

When one discovers—or is assigned—a topic where an adequate synthesis does not exist, the real work begins (and, optimally, that work will be stimulating and enjoyable). One has to search widely for relevant information and insights. Search engines are invaluable allies, but they have no boundaries. Accordingly, one needs personal discipline as well as knowledge of relevant scholarly disciplines. More importantly—and this is central to my argument—one needs ways of organizing the accumulating information.

Organizing and reorganizing information, numbers, data, visualizations, etc.—that constitutes the heart of synthesis. Here is where we draw on our multiple intelligences—no two people will synthesize in exactly the same way. (In my case, I discovered, to my surprise, that the musical and naturalist intelligences play an important role in my own synthesizing efforts.) One uses pictures, tables, charts, graphs, equations, mental models, mind maps, metaphors, stories, melodies, riddles, epigrams—whatever works!

Evidently the synthesis needs to work for you—that’s why you have undertaken it. (Unless it’s simply a homework assignment!) But you alone are not enough. You need to try out the synthesis on others—those friendly to your project, and those more critical or skeptical. And a cycle of revision and perhaps even reformulation may be necessary.

But life is short. Eventually the synthesis needs to become public (hence, my thirty books, including the one I’m discussing here) and you discover where it succeeds and where it falls short. (In my case, that discovery has come from book reviews as well as critiques from my four children.

I have come to know and understand synthesis chiefly from a life of scholarly research and writing. But the synthesizing mind is essential as well for political leaders, for managers and executives, for organizers of any complex activity—to paraphrase a character from the French playwright Moliere—“I have been synthesizing all my life without being aware of it!” On my website, www.howardgardner.com/, I am beginning to analyze the synthesizing capacities of individuals who are not primarily scholars.

As has become the practice these days, the book’s preface summarizes the book’s aims and content, as I have just done. No need to repeat those 1000 words here. But when I am asked to read aloud, I pick out passages like these:

p ix, the time in the fall of 1984, when I gave a talk about ‘the theory of multiple intelligences’ and realized that from then on, I would be a ‘public figure’ and might also come to be known thereafter as the ‘MI guy’.

pp 3-4, my early childhood and the secrets that my parents kept from me;

p 5, the parts of my ‘child mind’ that remain today;

pp 12-13, my visual problems and how I compensated for them;

pp 19-21, my ease with standard school testing along with my growing skepticism about what psychological tests can actually reveal about cognition and personality;

p 46, when I fell in love with the study of psychology, sociology, and anthropology;

p 53, why I loved college;

p 64, how, as a beginning doctoral student, I was viciously attacked by social psychologist Stanley Milgram and no one came to my defense—I still shudder when I think of this experience 55 years ago;

pp 68-69, why I hated graduate school and almost quit—the balance sheet that I drew up;

p 70, how I was ‘saved’ by my encounter with Nelson Goodman, a philosopher interested in the arts, who started a research group called Project Zero, which has been my principal intellectual home since 1967! (I was the co-director for 28 years and now chair the Steering Committee);

pp 82-83, how I retained my sanity in graduate school by shutting my office door and working on three quite different books;

p 99, my first days as a full time ‘soft money’ researcher, (I had to raise my own salary, chiefly from government sources), and how I spent my days—studying brain damaged veterans each morning and studying children with various gifts each afternoon;

p 117-118, how, as a consequence of this immersion with two distinctive and revealing populations, I came up with ‘MI theory’;

pp 133-135, my responses to the principal criticisms of MI theory;

pp 159-160, how an unfortunate experience with MI theory in Australia changed my life’s work (one Australian state was classifying racial and ethnic groups on the basis of their putative profiles of intelligences!);

pp 184-185, enter: the study of ‘good work’, to which I have now devoted more than a quarter of a century—see thegoodproject.org;

pp 197-198, why and how I have researched and written about so many different topics;

pp 216-217, the five most needed minds in the future, and where synthesizing fits in (to be specific: the disciplined, synthesizing, creating, respectful and ethical minds);

p 232, human vs computer synthesizing—what we should download to algorithms, what should continue to be undertaken by human minds (individually and collectively).

AND IN THAT HYPOTHETICAL TRIP TO THE BOOK STORE, PLEASE LEAF THROUGH THE PICTURES OF MY FAMILY—FIVE GENERATIONS; MY TEACHERS; MY LETTERS FROM GROUCHO MARX, JEAN PIAGET, CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS, EDMUND WILSON, ETC…. AND A PHOTO OF ME WITH TWO-TIME U.S. PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE ADLAI STEVENSON.

I believe that my book will initially draw three groups of readers: 1) those interested in my own history (largely family members and friends, perhaps colleagues and former students); 2) those who want to know more about the origins of MI theory, its principal claims, the diverse reactions to it, and how it has been followed up in the last three-plus decades; 3) those who are intrigued by the phrase ‘synthesizing mind’—the latter readers can learn what it is, how it is developed, how it can be educated and enhanced, and, if possible, how to strengthen one’s own synthesizing powers.

Though not intended primarily as such, the book also contains insights about what it was like to grow up in a ‘depressed area’ (northeastern Pennsylvania, once thriving because of anthracite coal) in the middle of the twentieth century—merely a mile away from my agemate young Joe Biden; to have inspiring teachers and mentors, as well as a smattering of anti-mentors and tormentors, and how one person succeeded in navigating a life in scholarship without following the usual career pathways within the usual scholarly departments.

To my surprise and pleasure, some early readers, reviewers, and interviewers have also found encouragement and even inspiration from aspects of my biography: especially my overcoming some personal and some physical handicaps; surviving a graduate training which was not pleasurable and sometimes quite punitive; being more of a book writer than an author of peer-reviewed, empirical studies; being able to go beyond—not becoming a slave to—what one is best known for, in my case ‘MI theory’.

I am not sure that I would advise anyone to do exactly what I did; but I firmly believe that if you have some talent, a strong will, and can negotiate setbacks, you can survive and perhaps even thrive in a variety of environments. I have long been inspired by the words of French economist and political visionary Jean Monnet: “I regard every defeat as an opportunity.”

Also, because I have studied and written about an unusually large number of topics, the book has given me the opportunity not only to discover links among these seemingly disparate subjects, but also to tie together this ‘network of enterprise’—this ‘through line’, as it were—in ways that make sense to me and, I hope, to others as well. And, going forward, I may be in a better position to understand what I do, how I do it, what may come next and why, and what may come after that.

Most important to me, I hope to be able to put ‘synthesizing’ on the map: why it is important, more today than ever before; why it has been relatively neglected by researchers; how it occupies an important, indeed invaluable niche, between journalism, on the one hand, and standard experimental social science on the other; how it might be nurtured by teachers, mentors, parents, on the one hand, and how we ourselves may sharpen our synthesizing capacities, to our own benefit and, if we are successful and strategic, to the benefit of those who encounter us and/or our work. Also, while some synthesizing can and should be done by computational devices and programs, the most important acts of selection and of action are and should remain distinctly human endeavors.

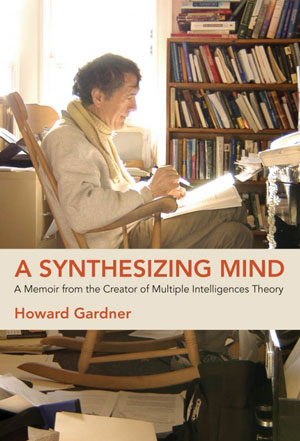

Trained as a psychologist, Howard Gardner is the Hobbs Research Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Best known for his ‘Theory of Multiple Intelligences’, Gardner has written over 30 books (translated into 32 languages), on a wide range of topics, including creativity, leadership, the arts, cognitive science, developmental psychology, ethics, and structuralism. He has been a major contributor to educational discussions world-wide and has most recently been studying the nature and provenance of ‘good work’ in the professions and in the polity. Gardner has received numerous honors, including a MacArthur Prize Fellowship, and honorary degrees from 31 countries all over the world. To follow Gardner’s work, please see howardgardner.com, thegoodproject.org, multipleintelligncesoasis.org, and asynthesizingmind.com.