Our earliest attitudes about copyright law are probably formed by elementary school teachers admonishing us not to copy. Seeing little Johnny and Suzy sent to the principal’s office for plagiarism sends a pretty clear message about the consequences of borrowing someone else’s work!

Copy this Book! What Data Tells Us About Copyright and the Public Good hopes to nudge the reader into questioning that ingrained anti-copying instinct. In fact, numerous recent studies show that modern copyright law stifles creativity, raises prices, and diminishes the availability of works to the public.

But mere statistics are pretty dry, so the book goes far beyond graphs and charts and tells the deep story of copyright with numerous illustrative anecdotes and stories. Think Bill Bryson or Neil deGrasse Tyson!

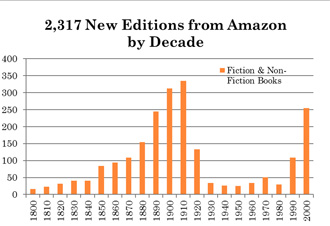

Copy this Book! starts with the alarming results of a random sample of new editions of books being sold on Amazon.com. Why are there so many more new books from the 1880s for sale than from the 1980s (and, no, it’s not because the older books are literary “classics”)?

Other chapters discuss (among many topics):

How Lunch atop a Skyscraper, the iconic photo of men perched on a steel beam high above Manhattan, reveals the disastrous law of copyright in images.

How Kurt Vonnegut’s successful battle with Random House opened the door for older authors (and their estates) to publish ebooks for the first time.

How porn parody movies teach us about fair use and the proper length of copyright.

How music ratings studies show a counter-intuitive effect of piracy on the music business.

How a study of images on Wikipedia (which required a valiant effort to reverse engineer the Google search algorithm) can teach us about the value of the public domain photos.

How publishers and firms like Getty Images convince the public to pay for free public domain works.

Sure, charts and graphs and data are presented, but the book is a narrative, a story most happily told through the experiences of authors, artists, musicians, and consumers.

Most of us don’t understand the profound impact copyright law has on our lives. Most have a sense that copyright protection should be designed to incentivize new creations, but we seldom think much about the actual content of the law. Or consider the shocking possibility that US copyright law might actually deter creativity, stifle availability, and raise prices for consumers.

Here’s a snapshot of new editions of books available on Amazon.com in 2011:

At the time the sample was taken, all books published in the US before 1923 were in the public domain. Because they are free for anyone to publish, even works from the 19th century are widely available. What about books from the 1930s to the 1980s? Why did they disappear? The best explanation is that their publishers let them go out of print. And since they are still protected by copyright, no one else can make them available. Copyright can make works disappear.

Copy This Book! also describes how copyright raises the price of books, deters the creation of derivative works like audio books, and stifles the creativity of composers, arrangers, and performers of music.

Stories of how copyright creates works with no discernable owners (“orphan works”) and how false claims of ownership of public domain works (“copyfraud”) deter the exploitation of the public domain, provide further illustrations of how badly calibrated US copyright negatively affects consumers and creators alike.

Copy This Book! is a happy wedding of my professional and public lives. Years of academic economic research have generated piles of data on the effect of copyright on public welfare, while years of novel writing (hopefully!) provide the book with a readable narrative style.

Apart from the Amazon graph depicted in the previous section, I would love a browsing reader to encounter the photograph on page 10 of the book showing workers perched on a steel beam, eating their lunch high above the Manhattan skyline. Why is it so difficult to determine the ownership (or lack thereof) of one of the most iconic photographs ever taken?

The frequent impossibility of determining the copyright status of a work is illustrated by the twisted history of the lunchtime image (which necessarily includes a consideration of Dr. Sheldon Cooper’s “Soft kitty, warm kitty” song from the “Big Bang Theory”). Copyright Office data confirms the shocking lack of public accessibility to photographic works taken in the middle of the last century.

Copy This Book! seeks to bring home the effects of endless expansion of copyright law on readers. Although each chapter illustrates this point in a different way, there is something especially compelling about the “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper” image and subsequent narrative.

Someone starting their browsing in the middle of the book, rather than the beginning, would encounter shocking examples of “copyfraud”: false claims of ownership of public domain works. What could be more enraging than a publisher claiming to own the copyright in the Declaration of Independence or the congressional 9/11 committee report? Yet, it happens all the time and constantly deters the republication of public domain works.

Hopefully, even a browsing reader will be prompted to visit Getty Images and learn the price people are charged to use public domain photographs! Of course, it might be easier to just buy the book and find out.

Finally, a quick look at the last page provides a browser with the punchline for the story, “if you simply cannot afford to pay for it and would not have bought it anyway, please copy this book!” Reading the book explains why this statement makes sense.

The consumer protection movement has energized the public to reconsider many of the products and services it encounters in the market. Clearly, we have become more discerning consumers of things like food, automobiles, and banking services. And we also have come to care about the laws that regulate our consumption.

Although consumer oversight of Congress and regulatory agencies is increasing in many areas, copyright law remains a hidden determiner of our cultural future.

Copy This Book! explains why we should care as much about the length of the copyright term as we care about the accuracy of organic labeling or the phraseology of consumer lending contracts.

Armed with dozens of studies, consumer advocates now have an arsenal with which to counter the ever-increasing demand of copyright owners for broader rights.

In other fields of law, large firms sometimes serve as surrogates for the public interest. For example, when big Pharma pushes for broader patent rights, Silicon Valley often pushes back, forcing Congress to consider what might be best for the public as a whole.

When it comes to copyright law, however, large publishers, plus the movie and music industries, have faced little or no pushback against their successful attempts to distort the law to their private benefit. Few pay attention to copyright “reform,” and the effect on the market for cultural goods is obscured.

Copy This Book! is not only a call to arms, but a provider of weaponry.

Paul Heald, the Albert J. Harno and Edward W. Cleary Chair in Law, joined the Illinois faculty in 2011 after 22 years at the University of Georgia School of Law. He is also a fellow and associated researcher at CREATe, the RCUK Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy, based at the University of Glasgow. He spent much of 2018 as an Erskine Fellow in the Economics Department of the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, and as a Research Fellow at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study in South Africa.