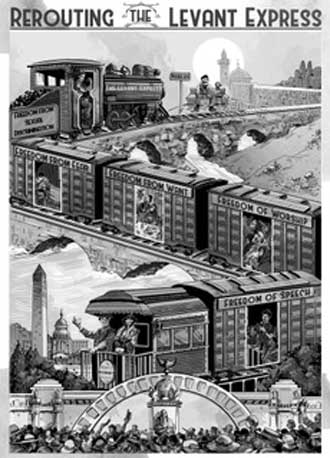

First, the book title, The Levant Express, is a metaphor representing the demands for human rights that raced across the Arab world like a high-speed train during the Arab uprisings of 2011. Within two years, the fast moving revolutionary contagion slowed to a halt. When the Arab Spring turned into the Arab Winter, some governments (Egypt and the Gulf monarchies) reestablished even more repressive authoritarian regimes, while other states (Libya, Syria, Yemen) devolved into civil wars. What led to those uprisings and their tragic consequences? My book addresses those questions by identifying how patterns of revolution and counterrevolution have played out in different societies and historical contexts. I then apply those insights toward offering hopeful and realistic proposals to reroute The Levant Express.

What makes my book unique are the arguments I offer for hope, and the paths that I offer for resuming the advance of human rights in the Middle East. Other experts view the region as trapped in an endless maelstrom, or offer incremental steps aimed at one or another immediate crisis. True, the region has been beset by a long history of political repression, economic distress, sectarian conflict, and violence against women. But that history pales in comparison to the tragedies of the West, which was also plagued by religious wars, and by two World Wars that brought Europe unprecedented devastation.

Hopefully, readers will be stimulated and informed by the lessons I draw from those European struggles and apply to the Middle East, and by my identification of current possibilities, including subterranean social forces for progress. I remind readers that before the defeat of Nazism, Franklin D. Roosevelt envisioned a post-war reconstruction effort based on foundational principles of freedom. His Four Freedoms (Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear) paved the way for the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Marshall Plan, Bretton Woods, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. History offers no better success story than these post-World War II endeavors. We need to remember that sustainable peace needs to be planned even during times of war.

In short, this book is attentive to the current plight of people in the Middle East. It also challenges the pessimistic malaise that undermines Western interest in developing substantive plans for regional progress. It prods readers to resist succumbing to populist, protectionist, and nationalist fervor, and to understand why a restored international liberal order requires a peaceful Middle East. For example, the refugee crisis in Europe cannot be addressed without human rights, political stability, and economic opportunity in the Middle East and North Africa. Our futures are intertwined.

When the Arab Spring began, I had an unusual vantage point. Living in the United Arab Emirates as a visiting professor, I was teaching one of the first human rights courses in the Arab World when protesters started flooding the streets in Tunis, Cairo, and beyond. The UAE was in the eye of this historical storm, and I was meeting regularly with diplomats, world leaders, scholars, and journalists. I had the privilege of teaching politicians and members of the Emirati ruling family, learning about their hopes and fears as upheaval shook the region. I also traveled extensively to hear from some of the people who were most affected, from human rights activists to refugees from civil wars. As a human rights scholar trained in political philosophy and history, I recognized patterns of revolutionary contagion and anticipated the turning points at which these uprisings would falter or come to fruition.

Those insights are represented in this book, in which I carry on the tradition of progressive realists—a category that includes people as diverse as Franklin Roosevelt and Antonio Gramsci—as I attempt to untie the Gordian knots that prevent a regional peace predicated on economic development and the advance of human rights. I consider how the pendulum, which has moved since 2013 from Enlightenment to counter-Enlightenment, can swing back toward a sustainable Enlightenment pole. These arguments remain relevant as protesters return today to Arab streets, and as repressive regimes face new domestic and international pressures.

The train of human rights progress, the Levant Express, is more than just a metaphor. I also propose (among other developmental projects) restoring an abandoned rail network—the Hejaz train that once connected major cities in the Middle East—as a way to reinvigorate the economy and connect people from different parts of the region. I am not the only one to see the potential of this idea, which is capturing the imagination of several non-Western countries. The vision of a Middle East connected by high-speed rail, new roads and trade routes is attracting financial, commercial, and governmental interest, spearheaded by China; and the West would do well to pay attention.

The book is filled with other details about this and other actual and planned regional projects consistent with basic human rights aspirations. It is informed by a deep understanding of political theory, history, economics, and law—fields that often are marginalized within Middle Eastern studies. But it is also highly readable and light on academic jargon, and very accessible to a nonacademic audience. Artwork, maps, poetry and rap lyrics are used to dramatize events that led to the changing political seasons since the Arab uprisings—and to stir the imagination about what could possibly happen in the future.

An accomplished artist, Brooke VanDevelder, worked with me to create customized illustrations that serve as frontispieces for each of the book’s three sections. If a potential reader is just browsing, those images will provide a fitting introduction to the spirit and content of each section. Those who have a little more time will appreciate the brief introductions to each of the book’s three parts, along with the overall introduction to the book. That’s where I tell some of my own story, even including a personal poem called, “Farewell to Abu Dhabi,” and where I outline the main themes of the book.

I suspect that some readers will jump to particular chapters to see what I have to say about issues in which they are most engaged. For example, the chapters “Frost in Jerusalem” and “Remembering the Future” address the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in significant detail, with nostalgic hope for what may yet be accomplished in that tortured part of the world.

Many readers have been particularly struck by the chapter on women’s rights, and I agree that it is especially important. It has been said that the degree of women’s emancipation provides a measure of human emancipation in general. This chapter looks at the struggle for women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa, searching for signs of progress in some of the world’s most repressive regimes. As elsewhere in the book, I focus on FDR’s Four Freedoms, and I argue that women’s frustration with inequality is building as in a pressure cooker. That’s why I call the chapter “The Female Time Bomb.” I close the chapter with these words: “As long as a patriarchal social and religious system keeps women silent in the public sphere, sexually dissatisfied and disempowered in the family, impoverished despite their increased level of education, and living in fear despite their growing skills of resilience, pressures will build toward a new women’s rights contagion, and a new sexual revolution, occurring in the Arab world—one that would reorder families and destabilize autocratic regimes. It may well be women who reroute the temporarily derailed Levant Express toward new democratic pastures.” As I predicted, women are at the forefront once again in the protests that have rocked Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran during the past year.

This book opens with a poem, “Farewell to Abu Dhabi,” which I wrote on the plane as I completed my Gulf sojourn and returned to Denver. Reflecting on the people I was leaving behind, I thought of them as uncertain travelers like myself, struggling to find their way through tempestuous times. “I will bring you along to my new refuge,” I wrote, “an ambassador for dreams yet to bloom.” While I use poetry and creative images to take readers to the realm of the possible, I advance and document practical proposals designed to draw the attention of an interested audience, analysts, and policy-makers.

No one can offer a blueprint for the future, but I sketch alternatives that are today obscured by sectarian conflict, religious extremism, and authoritarian repression. I invite others to enter into this conversation by adding, altering, or proposing different paths. I am gratified that some of these ideas are making inroads in palaces, parliamentary offices, businesses, and other audiences. Amidst war fatigue, such proposals, based on fundamental principles of rights, may present themselves as more realistic and viable alternatives. Roosevelt reminded us in an even darker time that “the world will either move forward toward unity and widely shared prosperity or it will move apart.” I agree, and would add that the stakes are too high and the world cannot afford to lose.

Micheline Ishay is Distinguished Professor of International Studies and Human Rights at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, where she serves as Director of the International Human Rights Program. She is an affiliate faculty member with the Center for Middle East Studies and in 2008 was named University of Denver Distinguished Scholar. She has held visiting professorships at Hebrew University, Jerusalem and Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, along with fellowships at the University of Maryland and the Bellagio Center (Rockefeller Foundation) in Italy.