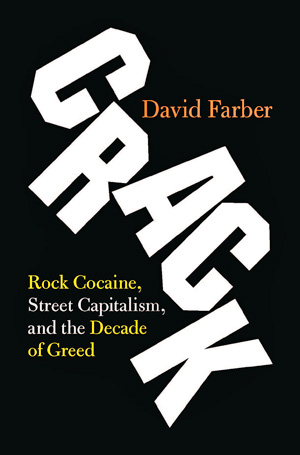

Crack tells the story of the young men who bet their lives on the rewards of selling “rock” cocaine, the people who gave themselves over to the crack pipe, and the often merciless authorities who incarcerated legions of African Americans caught in the crack cocaine underworld.

Based on interviews, archival research, judicial records, underground videos, and prison memoirs, Crack explains why, in a de-industrializing America in which good paying, dignified jobs in inner cities were rare, selling rock cocaine made cold, hard sense to a broad cohort of young men. The crack industry was a lucrative enterprise for the “Horatio Alger boys” of their place and time, especially in an era in which market forces ruled and entrepreneurial risk-taking was celebrated.

These young, predominately African American entrepreneurs were profit-sharing partners in a deviant, criminal form of economic globalization. Like their mostly legit counterparts in 1980s and 1990s America (e.g., Donald Trump and his “Art of the Deal”), they embraced the “creative destruction” that was simultaneously tearing apart communities and reinventing American capitalism.

Hip Hop artists often celebrated the exploits of the crack kingpins and their crews. Biggie Smalls laid out “The Ten Crack Commandments” for aspiring dealers. In “Kilo,” Ghostface Killah of the Wu Tang Klan explained the joy of moving weight and reaping the benefits of seemingly unattainable wealth. For some of their peers, crack dealers were the neighborhood Robin Hoods. They were the “social bandits” of their economically beat-down streets.

Overwhelmingly, Americans—across racial lines—did not take so kindly to the crack dealers and “crackheads.” Crack dealers defended their drug selling territories with unvarnished violence. Homicide rates soared in poor, inner city neighborhoods. Innocents were caught in the crossfire. Crack addicts robbed, stole, and prostituted themselves to pay for their rocks. Poor people were prey for crack dealers; families and neighbors in poor communities paid the heaviest price for the localized crack epidemics of the 1980s and 1990s.

Americans, fueled by fear and sometimes hysteria, cracked down on the sale and use of rock cocaine. Congress, supported by presidents Reagan, Bush, and Clinton, passed draconian federal laws that punished crack dealers with sentences that often exceeded those handed out to murders and rapists. State and local authorities followed suit. Authorities spent billions to build a merciless system of mass incarceration. Overwhelmingly, that punishing carceral machinery targeted black Americans.

Crack takes a hard look at the dark side of late twentieth century capitalism. It examines how an explosive mix of deviant globalization, racial inequities, and the war on drugs shattered American society.

I never smoked crack. I did live in New York City in the 1980s and 1990s at the height of the crack era. Until my wife and I discovered it, our little boy had an impressive rainbow-colored collection of crack vial caps. Less than three blocks from our apartment, two rival crews sold thousands of rocks everyday. Crack users binged in our unlocked building vestibule. Anything not locked down in our neighborhood was stolen. At the time, I was horrified.

A bit over a decade later, living now at the ragged edge of Center City Philadelphia, a small crack crew operated in the alley below my living room window. By the time I lived in Philly, beginning in 2004, crack had largely lost its massive appeal. Other drugs, including meth, opioids, and potent strains of cannabis, had replaced it. But my crack-dealing neighbors had found a market niche—the men who congregated near a homeless shelter a few hundred feet from my building.

I got to know the crew’s head of operations. He was a civil and fascinating man (when he was not too high on the blunts that he smoked endlessly). Our conversations planted a seed and, eventually, I chose to write this history of the crack cocaine years in the United States.

I saw a history of crack as a way to think about how drug regimes have figured American life. Though the story does not usually get into our history textbooks, American life has been fundamentally shaped by our collective desire to use and regulate narcotics and other intoxicants that affect our state-of-mind. For nearly fifty years, in an unprecedented way, we have waged a “war on drugs” that has profoundly altered the lives of the American people.

In the 1980s and 1990s, crack cocaine was in the crosshairs of that drug war. As a small population became dangerously addicted to crack, tens of millions more decided that crack cocaine was a terrifying danger and unleashed a punishing regime that has rarely been matched in American history. Dealers, even those who were caught selling less than a paper clip’s weight, had their lives destroyed. Rather than treat the lure of crack cocaine as a public health crisis, Americans responded to crack use by locking up tens of thousands of crack dealers, who were disproportionately poor African American men. A history of the crack years, I believe, tells us a great deal about race, class, economic opportunity, and the contested nature of mercy and justice in the United States.

While Crack is, as books go, on the slim side, it covers a lot of ground. While I hope the chapters on the history of cocaine, the lure of crack, and the crackdown on crack cocaine will captivate readers, I think many will be most fascinated by the chapters in the book that explore the crack trade as a business. To explain how crack distribution worked, I touch on a lot of different places and people, but I concentrate on the history of the crack industry in two cities: New York and Chicago.

Of New York, I tell the story of the “Supreme Team,” which operated in Queens. Led by Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff, this crack crew became notorious for its economic success and for the violence the crew used to protect and expand its business. The Supreme Team became the stuff of Hip Hop myth and legend. In real life, as readers will learn, things went less well for most of the Team’s leadership, many of whom, decades after their criminal organization was taken down, are still imprisoned.

Chicago’s crack distributors emerged out of the city’s well-organized and powerful street gang culture. At the top of the crack pyramid in Chicago stood the Gangster Disciples (GDs), led from prison by the irrepressible Larry Hoover (the man Kanye West asked President Trump to pardon in 2018). The GDs controlled many of the massive public housing projects in Chicago and at one point had tens of thousands of gangsters selling crack cocaine in a highly organized and disciplined network. Along with their main rivals, The P. Stone Nation, the GDs had the city locked up tight. The story of crack distribution in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s is an alternative history of life in America as it is usually told. It was a difficult history to research, and I think it is the part of the book that will hit readers the hardest.

In part, I wrote Crack to tell a dark story, a historical accounting of the underside of the American dream. We’ve grown inured, I think, to words like economic inequality, racism, and mass incarceration—for many, they have lost their visceral impact. In Crack, I do my best to explore the lived experience of racial injustice, of what it felt like to endure grinding poverty, of how it felt to believe that your only opportunities were ignominious ones. And then to have discovered, as one of the men I interviewed called it, “white gold.”

In much of American society during the Age of Reagan and Reagonomics, disinvesting in inner city communities and denigrating people living in poverty became political common sense. In another part of American society, during that era, selling crack cocaine became an economic lifeline; it became a way to live out dreams of self-worth and material riches. And on the other side of that economic transaction, for too many poor people of color who had become economically dislocated and socially alienated from mainstream society, crack cocaine was a balm that offered solace for their hard lives.

Good history—even recent history—I think, places readers in a different world. In Crack, I want readers to see the world as it existed for many poor Americans, especially poor African Americans, at the tail end of the twentieth century. And I want readers to begin to understand why crack cocaine, as a product both to sell and consume, made sense to some of those people. This book about the crack cocaine industry in the last decades of the twentieth century explores how the go-go economy of that era looked to those on the wrong side of that era’s massive economic divide. It explores, too, how powerful Americans helped create that divide and then built a carceral state to house so many of those who had been left out of America’s bounty.

David Farber’s books include Chicago ’68; The Age of Great Dreams; Taken Hostage; Sloan Rules; Everybody Ought to be Rich; and The Rise and Fall of Modern American Conservatism. He is currently the Roy A. Roberts Distinguished Professor at the University of Kansas. He and his wife, the historian Beth Bailey, live outside Lawrence, Kansas, on the prairie, in a house with a grass roof.