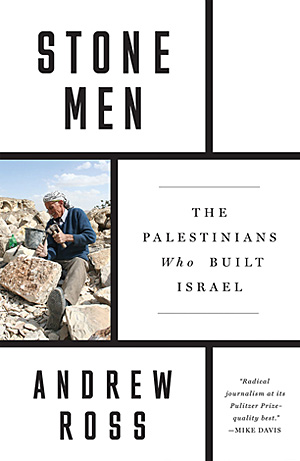

Ostensibly, Stone Men is about the lives and labors of Palestinian stonemasons. These are men who work in the West Bank stone industry—in quarries, workshops, and factories—and have a rich and venerable history behind their craft. Palestinian masons have been sought out for centuries for their superior artisanal skills. For the book, I interviewed them at every point in the production and supply chain, along with the construction workers who follow the journey of the stone across the Green Line and onto building sites in Israel or in the West Bank settlements.

The Central Highlands of the West Bank harbor some of the best quality limestone deposits in the world, and they are the one natural resource that Palestinians still have under their control. Sadly, most of the quarried stone is used to build out Israel, the state of their occupier, and its spreading archipelago of settlements in the West Bank. Also, to some degree, Palestinians suffer from the same “resource curse” as oil-rich countries. The extraction of the stone (sometimes known as “white oil”) is only lightly regulated and so strip-mining ravages the environment and sickens the workforce.

The Israeli construction industry is heavily reliant on Palestinian labor and on the West Bank stone industry. I felt that my reporting (I write in a style I call “scholarly reporting”) might be a good way to tell the story about the colonial nature of this economic interdependency between Palestinians and Israelis, while documenting the daily routines of the workforce. Of course, it’s a very asymmetrical relationship. For example, the Israeli authorities have finessed a policy of economic pacification to discipline the workforce—we will issue work permits in return for your acceptance of the status quo, but if you, or any family member, steps out of line, or gets arrested, the permits will be withdrawn. Because Palestinian development has stagnated under the 52-year occupation, there are few alternatives on the West Bank that pay more than a starvation wage, so it’s what I call a compulsory workforce that crosses the Green Line every day.

So, too the Israeli economy benefits at all levels from this arrangement—workers return to the West Bank every night, posing no social burden on the Israeli state, and they spend their pay on Israeli goods at Israeli prices in their hometowns. That’s a win-win for Israel. But the occupation is also good for profit-takers on the Palestinian side. There are the crony, or comprador, capitalists around the Palestinian Authority, then there are the stone industry owners themselves, who constitute a smaller petty-bourgeois economy, and, last but not least, the middlemen subcontractors who take a hefty cut from the labor supply chain.

Why did I wrote the book? I was surprised to find that there is no published study of this stone industry, which is the largest private sector employer in the West Bank and generates the most GDP and exports from the Occupied Territories. Nor is there very much literature on Palestinian livelihoods. Palestine-watchers are focused on other things—land theft, demolitions, population displacement, soldier brutality, mass incarceration, the spread of settlements—and all for very good reasons. As a result, perhaps, there is less knowledge about what working-class people, especially, do to put food on the table every day for their families. I wanted to help fill that gap in attention, and felt that, as a sometime labor ethnographer, I could contribute something useful.

In addition to the stone and construction workers, I also interviewed a range of company owners, officials in the new trade unions in the West Bank and Israel, and engineers and architects involved in restoring Palestinian built heritage (at Riwaq, Bethlehem’s Center for Cultural Heritage Preservation and Taawon’s Old City Revitalization Project). The book also features some case studies: two national-level building projects in the West Bank (Rawabi and the Palestinian Cement Factory), and, in Jaffa, an analysis of what I call Ottomania—or gentrifiers’ new appetite for vintage décor and buildings in all that remains of the old city.

I also wanted to make room for some larger arguments about the history of Israel/Palestine and why we should be promoting full civil and political rights for all who live in the territories “between the river and the sea,” and whose ancestral lands are located there. So another part of the book reviews the history of employment in the construction industry, from the last decade of the Ottoman era through the Mandate, and then after the Nakba and Naksa—to confirm the decisive role played by Palestinian laborers and masons in the building of houses and infrastructure.

Who Built Israel? The given wisdom is that Jewish settlers did. Unused to manual labor, they learned on the job and made “new Jews” of themselves according to the doctrine of Labor Zionism. But the labor record I review in Stone Men is quite murky on this point and has been obscured by the agrarian romance of the kibbutz and the pervasive influence of nationalist mythologies. While Palestinians have always been at the core of the workforce, there have been at least three large-scale efforts to replace their labor: in the Conquest of Labor campaign in the early decades of the twentieth century; then after 1948, with the importation of Mizrahi Jews; and again after the first intifada with the recruitment of migrant workers from overseas.

In spite of these efforts, which were only partially successful, employers, especially in the construction industry, have always preferred Palestinian workers, and still do (today, there are more workers from the West Bank employed in Israel and the settlements than ever before). Acknowledging that Palestinians have built Israel (along with other states in the region, like Joran, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE) helps us understand how and why they should have labor-based claims on rights as well as claims on lands stolen during the Nakba and since.

Now, I am aware that this argument has not fared all that well for laboring populations in other countries. Think of the African-Americans, Irish, Chinese, and Mexicans who have built the United States. Pushing for full social inclusion and rights on the basis of their foundational labor did not work for them in the short-term, but, over time, the moral force of the argument has translated into fuller acceptance of their civil and political rights. In the case of Palestine, the argument is even stronger; we are not talking about populations brought from elsewhere; these are people who labor on their own lands to build another people’s nation-state.

My journey to this book began in Abu Dhabi, where I had been doing research, with colleagues in the Gulf Labor Coalition, on South Asian migrant workers (documented in the book The Gulf: Hard Labor/High Culture). The government did not like what we were doing there so they banned us from entering the country. Shortly thereafter, some of us re-grouped in Palestine to help make a film, and I found myself doing interviews, at the Green Line checkpoints, with people who were, in effect, migrant workers in their own land.

My decision to pursue the research was also driven by a personal effort to follow through on the BDS—Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions—resolution vote passed by my professional association, the American Studies Association, in 2014. It’s one thing to vote for such a resolution, but how do you make good on the analogy often cited as an argument for the resolution—that our discipline’s knowledge about settler colonialism in the U.S. had some intimate relevance to the ongoing record of Zionist settlement in historic Palestine? Like many others in the field, I felt a responsibility to engage further in my own research. So, too, I joined the organizing committee of USACBI, the American branch of the BDS movement.

The book was written for the general reader, so no specialist knowledge of the region is required. I am not a Middle Eastern expert myself, which makes it easier to approach readers roughly on the same level. But I also wanted to put some materials and reasoning on the table that might be useful to front line advocates of Palestinian liberation. Hence the argument I make about political sweat equity—based on the principle that building a country should translate into political rights within it. Palestinians have put in more than a century of toil building the Jewish “national home,” and most other assets on these lands. What rights accrue from that long inventory of labor, and how can this record of contributions feed into the transitional justice claims needed to bring about the one-state solution with full rights for all?

Andrew Ross is Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis and Director of the American Studies Program at New York University. A contributor to the Guardian, the New York Times, The Nation, and Al Jazeera, he is the author or editor of more than twenty books, including Creditocracy and the Case for Debt Refusal, Bird On Fire, Nice Work if You Can Get It, Fast Boat to China, No-Collar, and The Celebration Chronicles. His new book, from Verso, is titled Stone Men: The Palestinians Who Built Israel.