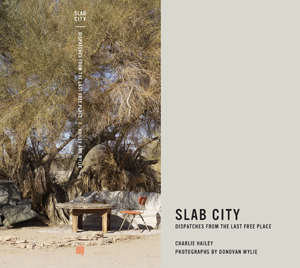

Slab City is known as the “last free place.” This remote settlement in the southern California desert occupies a decommissioned World War II military camp. Only its slabs and tank-rutted roads remain. Slab City also occupies the legacies of Jeffersonian land policy. Its one-square mile area is one of the last remaining Section 36 plots dedicated exclusively for public use in the National Land Ordinance system. A collaboration between an architect and a photographer, this book sets out to understand the idea of freedom that has been built on those eponymous slabs by a community of anarchists, artists, retirees, snowbirds, squatters, survivalists, and veterans.

Seven decades in the making, Slab City is one of the most enduring temporary settlements in the United States. It endures despite hardship. All of the elements of a city’s infrastructure are here, but the roads are crumbling, the sewers have been capped, the million-gallon water tanks are empty, and the high-tension lines of the nearby power grid pass high overhead. The canals that flank two sides of Slab City like defensive moats rush toward the Imperial Valley’s fields of iceberg lettuce and northward to the lawns of Palm Springs. Like the soldiers bivouacked at Camp Dunlap in the 1940s, Slab City’s inhabitants—known as “slabbers”—are also effectively training to live in the desert, where the rights of public land meet the difficulties of off-grid living.

In Slab City, a resident’s tenure of a site requires physical occupation. And when you can’t be physically present, the structures you have made stand in for your absence. In our field work, Donovan and I set out to understand this place through the things its residents have made. Our collaboration took on Benjamin Buchloh’s charge to discover how creative practice (in our case, writing and photographing) can study marginal places. We hoped to understand new territories caught between complex pasts and indeterminate futures that mix autonomy, necessity, and control. Our method was to read and interrogate the built environment: its shelters, boundaries, markers, art installations, vehicles, cemeteries. In the process, constructions became characters; structures took on personas.

Between its introduction and conclusion, the form of the book has five acts—camp, perimeter, ration, facilities, and drawdown. Each act gathers the scenes and elements that make up this place and tells its story. “Ration,” for example, unpacks the necessary provisions of off-the-grid life in the desert—from tin cans to shade cloth, from cardboard to Slab Mart. “Facilities” narrates Slab City’s ad hoc infrastructures (including a hot springs bath, an improvised public shower, an empty Olympic-sized pool, a pet cemetery, and a library), as well as individual building projects of its residents (including a cave shelter carved into the berm of a canal and a hut made of pallets and palm fronds). Reading Slab City from start to finish follows the rising and falling actions of life on the slabs, but it can also be read more instinctively.

Each scene is short, and readers might choose to flip through the book, stopping at particular photographs or stories, in much the same way that Donovan and I explored the place. Each day, we set out with a particular theme in mind, whether it was boundary or grid or horizon, but our walks through the slabs always yielded other discoveries and insights that we had not expected. One morning, we were walking near the perimeter of the original military camp, and the low sun cast a series of long shadows that formed a nearly perfect line. We had discovered the remains of the camp’s southern perimeter fence. Its posts had long ago been salvaged (someone cut them off a few inches from the ground) to become building materials in Slab City.

A starting premise for our work was that camps, like Slab City, accommodate conditions that might otherwise remain without space. Camps are also bellwethers—early indicators of change and registers of the challenges faced by those who camp, whether by choice or out of necessity. It is true that Slab City, as the “last free place,” is a camp of autonomy where slabbers can experiment with ways of living and building. There are very few places where you have the independence to build and tear down at will. But its residents also contend with the weight of that freedom, the transience that goes along with it, and the depth of a history that extends well beyond the slabs. Studying Slab City, we found evidence of broader narratives that have defined a country and its identities—legacies that continue to be debated. The depth of Slab City’s multivalent histories and contemporary practices reexamine frontier and land tenure, resources and resourcefulness, Manifest Destiny and “city on a hill,” and migrancy and a country’s internally displaced people.

Slab City is built on layers of past settlements. The residue of the military camp is there, and some residents curate its memory as a form of patriotism. Immediately adjacent to Slab City, an active bombing range is also a constant reminder of that recent past. Much earlier, this site hosted the camps of Cahuilla Indians who harvested clams and fish along the shore of the natural lake (sometimes connected to the Gulf of California) that later became the accidentally created Salton Sea, when human efforts to control the Colorado River catastrophically failed. On your way to Slab City, you uncannily emerge from below “sea level” (there’s a small sign along the road) to reach East Mesa, where slabbers now occupy the ancient coastline amid sand, concrete slabs, and shell middens. Soon after the military camp was decommissioned, its slabs hosted migrant farm workers harvesting creosote.

Donovan and I are both interested in the architectures of resistance and adaptation. Slab City is an effort to synthesize Donovan’s ground-breaking studies of the architecture of control with my interest in emergent built environments that must contend with transience. Questions we have asked here and in our continued collaboration are: What are the architectural consequences when freedom and control overlap? What happens when freedom from intersects with freedom of? How might public land host private aspirations? How to make home in an unhomely place? What are the material consequences when desire and need come together in a self-governed place? How do makeshift dreams ride the desert sea like concrete slabs on sand?

When you pick up Slab City, you might open it to Donovan’s photograph of an A-frame shelter made of pallets and cardboard. Late one afternoon in June, its builder gave us a tour of its three levels that included a lounge, two bedrooms, a workshop where he hacked the proprietary systems of rechargeable power tools, and a loft where you could see the Algodones Dunes and the U.S. Mexico border beyond. To the east, we saw plumes of smoke from exploded ordnance in the still-active military range just across the canal. For us, this structure held the personal aspirations of its builder as it also reflected the core of Slab City as a collective laboratory to test freedom in its many built forms.

The A-frame also indexes the resourcefulness and resilience in its materials—the pallets came from the local Target in El Centro but had previously crossed borders and supported goods along the 21st century’s global supply lines, and the cardboard had packaged a recent delivery of photovoltaic panels for one of the massive solar farms nearby. To deflect the harsh desert sun, the cardboard was coated with white paint that came from Salvation Mountain.

In Donovan’s photograph, the flags above the A-frame have slackened in the dry heat of afternoon, and it is as if the builder has taken a break from painting and stepped back to admire his work. When I returned last year, this structure was gone. Across the road, a new pallet shelter had been built with a steeper A-frame, inclined like hands clasped in a kind of prayer.

Slab City is a field guide to a remote, transitory place. A folded map in the back pocket shows the layout and inventory of the military camp’s 1946 facilities. We carried that map each day we walked among the slabs. It helps locate the sixty-five slabs that have remained after the camp was decommissioned and its structures were removed. Like the slabs, the map is also a substrate for coming to terms with this place, for understanding how Slab City’s residents endure the difficulties of desert life and the frequent challenges to its public status. To pour concrete on sand is to test permanence in a mutable place. To live in Slab City is to experiment with the idea of freedom in a vestige of frontier space. And to write about and to photograph Slab City’s structures is to narrate an ongoing struggle between autonomy, necessity and control.

Charlie Hailey is Professor of Architecture in the University of Florida’s School of Architecture. A registered architect, Hailey has received numerous awards and grants, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Graham Foundation grant. He is the author of Design/Build with Jersey Devil (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016), Spoil Island: Reading the Makeshift Archipelago (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space (MIT Press, 2009), also featured on Rorotoko, and Campsite: Architectures of Duration and Place (LSU Press, 2008). His most recent book Slab City: Dispatches from the Last Free Place (MIT Press) with photographer Donovan Wylie was published in October 2018.