Edward Lear, the author of ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’ and ‘The Quangle Wangle’s Hat,’ is rightly beloved as a nonsense poet. But few people know that he was also a brilliant musician, who sang and played the piano, the flute, the accordion and the small guitar, and a composer, who published twelve beautiful settings of his friend Tennyson’s poetry. Lear was also a naturalist, whose vivid lithographs of new species of animals and birds were consulted by Charles Darwin, and a landscape painter of surpassing skill, who taught Queen Victoria to draw. My book is the first study to examine Lear fully – as a musician, a visual artist, a naturalist, and a religious dissenter – relating all of these endeavours and identities to his writing. It places Lear firmly within the social, cultural, and intellectual life of his time.

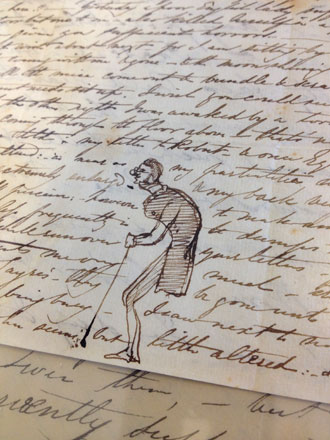

Inventing Edward Lear crystallizes insights gained over six years of research, during which I transcribed over 10,000 pages of unpublished manuscript. It contains many pictures and writings by Lear that have not been seen before. Probably my most exciting realisation was that all of Lear’s poems are really songs. I recovered music for some of his re-settings of comic words to existing tunes by Thomas Haynes Bayly and Thomas Arne. I traced songs that we know from his diaries Lear regularly performed. And I began the process of recording, with the help of pianist David Owen Norris and various singers, the music that Lear wrote, parodied, sang and listened to throughout his long life. Readers of my book (and even those who don’t read it) can listen to these recordings at my website: edwardlearsmusic.com

Lear performed all of his nonsense poems, and many other poems by Tennyson, Swinburne, and Shelley, to music. He also had a lively repertoire of contemporary comic songs, such as ‘Tea in the Arbour’, in which a town-bred visitor takes tea with country friends and is bothered by caterpillars in his tea and spiders in the butter, gets tar on his trousers, is peppered by birdshot, and is finally caught in a man-trap! Lear must have played this Harold Lloyd-style comic role to perfection, as friends forty years on still recalled him singing it. Lear was adept at transitioning, on improvised piano, from high tragedy to breathless comedy. Once we know that songs like ‘The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò’ are designed to sit uneasily – but brilliantly – between the sentimental yearning of drawing-room ballad and the cockney wordplay of Victorian musical-hall songs about foolish suitors, then it becomes easier to appreciate their genius. Lear creates a feedback loop between pathos and absurdity, where sentiment always threatens to be silly, yet the absurd frequently becomes moving. He makes us laugh and cry simultaneously.

My book relates Lear’s work to the intellectual and cultural life of his age in several different ways. I investigate Lear’s anger as a religious dissenter of an Independent cast, who felt that he was ‘damned’ by the Anglican Athanasian creed, and how his determination to read the Bible in his own terms, refusing ‘parrot prayers’ and ‘priestcraft,’ shaped his life and art. Lear’s sense of exclusion and strong belief in a ‘Broad Church’ made him a Liberal by habit and disposition. This affects many of his works, from ‘The Scroobious Pip’ – a character who refuses all categorisation – to the Quangle Wangle, who offers a happy home on his enormously ‘broad’ hat to a diverse band of creatures.

I also examine Lear’s natural history watercolors and lithographs. Lear was employed by patrons including the Earl of Derby to paint rare creatures, new to science, such as the ‘whiskered yarke.’ This heightened his awareness of species categorisation and theories about how plants and animals might be related. The 1830s and 1840s were full of speculation about zoophytes, which fused plant and animal characteristics, and cartoons of people staring at creatures in the London zoo, in mirror pose. Lear’s limericks often explore animal-human relations, evoking sympathy on both sides. I was especially intrigued by Lear’s comic drawing of the ‘Owly-Pussey-catte’: a hybrid creature he invented for some friends’ children in the 1830s. It is owl above the waist and cat below it. This cartoon was created almost forty years before Lear wrote his most famous poem, ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat.’ It suggests how rooted his nonsense is in ideas about hybridity. In Lear’s darker sequel to ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat,’ the cat has committed suicide, leaving the owl to act as single parent to their offspring, who are partly little beasts and partly little fowls. The females are cats; the males are owls. Lear persistently uses interspecies pairings to think about surprising equations in sexual algebra and how impossible partnerships may sometimes be possible, despite their difficulties. Lear was himself almost certainly bisexual, and I find it touching that without exploring sexuality directly, he leads us to think ‘outside the box’ of conventional matches in his era.

One of the joys of working on Lear was the opportunity it gave me to look carefully at his paintings, many of them in private hands. As a landscape artist, Lear was open to new techniques and voluntarily joined the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, calling William Holman Hunt his ‘daddy’, Thomas Woolner his ‘uncle,’ and (naughtily) John Everett Millais his ‘aunt.’ My book explores the political and aesthetic choices involved in Lear’s Pre-Raphaelitism and links his astonishing oil of Beachy Head (1862) to Frederic Church’s painting The Icebergs (1861). Lear paints Britain as a frozen Arctic, whose political climate can no longer support him. He spent most of his adult life in Italy, partly for its sunshine, but equally for its tolerance.

If you pick up Inventing Edward Lear in a bookstore, I hope you’ll turn to the pictures first. I would! Maybe you will be delighted by the imaginary enormous Hippopotamouse Rabbitte with its Lilliputian attendants feeding it lettuce; or by Lear’s atmospheric early sketch of Langdale in the Lake District; or by his astonishing self-caricature (drawn in his 20s) as an old man, stooped and with a stick, his spectacles appearing to slide down his nose like snowballs. All these appear here in print for the first time.

My book isn’t a biography, though you can glean the essential facts of Lear’s life from it, including a lot of brand-new material about his early friendships and home life. It was liberating not to have to follow Lear on every one of his innumerable journeys and visits. You can read all about those in Vivien Noakes’s or Jenny Uglow’s lives of Lear. I wanted to have the space to look closely at Lear’s work, offering new readings of most of his best-known poems, and engaging closely with the life of his mind, his ideas, his moods, his artistic practices, his reading and viewing. I wanted to be able to draw connections between his work as a writer, an artist, a musician, and a naturalist, suggesting that rich interdisciplinarity was the fundamental quality of his mindset, his oeuvre. The advantage of each chapter being thematic is that you can read them in any order, guided by your own particular interests.

However, I really hope that – sooner or later – you will find your way to Lear’s music, which is the subject of chapter one, and listen along to his songs while you are reading. I think you’ll agree that Lear’s setting of Tennyson’s ‘Tears, Idle Tears’ compares favorably with song-settings of the same poem by Arthur Sullivan and Ralph Vaughan Williams. In fact, I think it is better. You’ll also hear the musical echo of Lear’s Tennyson setting ‘Sweet and Low’ in the chorus of his nonsense poem ‘The Jumblies.’ The music of the first fits perfectly to the cadences of the second. That realisation clarified for me why ‘The Jumblies’ is a melancholy, wistful poem as well as a happy, wishful one. It is both a lullaby for children and a lullaby for childhood – full of musical regret and emotional longing.

In my final chapter, I look at Lear’s life-long history of self-caricature – always as a small creature, a snail, a bee, a bird – and how his self-presentation as an object of amused sympathy has affected his reputation as a poet who is loved but has not until recently been accorded serious critical attention. Lear usually gave his illustrated letters, poems, songs, alphabets, and botanies, as gifts; they were only subsequently published. In his own words, he was an ‘Adopty Duncle.’ This, too, has affected how we approach Lear’s work. It remains in the realm of gift; Lear’s exuberant but self-deprecating, cartoon body is part of the gift. He became identified with his nonsense and was sometimes hailed as ‘Book of Nonsense’ by strangers in hotels. His nonsense is created in social dialogue; it creates a game for more than one player, a song for more than one voice.

I think we should value tremendously highly the personal, affectionate nature of the relationship Lear builds with each reader, while also treating him with the respect we give to other Victorian polymaths he knew – John Ruskin, Alfred Tennyson, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Elizabeth Gaskell, William and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. I would like my book to be a step in that direction.

To take entirely at face value the comic, small and ungainly figure of Lear that he promulgates in cartoons – the Lear who hangs on the horns of a mouflon or like a pupating caterpillar in a bag from a tree – runs the risk of re-creating in different form the patronage on which he depended during his lifetime. Lear performed dependency, just as he performed hanging from his inside-out umbrella when the wind sweeps him away, or as he performed the hapless protagonist of the comic song ‘Tea in the Arbour.’ If we assume that Lear’s poetry is always chiefly and directly about his feelings at the moment of composition, we are reading cabaret as soliloquy.

Lear was an intellectual who liked the company of other intellectuals. His closest friends included some of the foremost Cambridge scholars of their generation; the women whose company he preferred were authors, musicians, artists, travel writers, linguists, and translators. He read widely and thoughtfully all his life, consuming periodicals and books in several languages that included philosophy and religion, poetry, essays, biography, letters, natural history, travel, novels, and parliamentary reports. He was taller, slimmer, fitter, more capable, more attractive to others, less isolated than is often assumed. In many cases, we can read Lear only through the lens of his self-mockery – as it is such an essential part of his letters and diaries – but it is vital at least to recognize how effectively Lear created his nonsense persona. Only by recognizing Lear’s self-fashioning as a character and responding to his ideas, rather than merely to the pathos of his biography, can critics fully appreciate his art. For ‘Edward Lear’ has proved, in many ways, to be Lear’s greatest and most enduring invention.

Sara Lodge is a Scottish writer of non-fiction, fiction, speeches, and journalism. She once worked as a speechwriter for Kofi Annan at the United Nations. She is currently Senior Lecturer in English at the University of St Andrews, specializing in nineteenth-century literature and culture. She has written books on the comic and social protest poet Thomas Hood (1799-1845); on the critical history of Jane Eyre; and on the poet, artist and composer Edward Lear (1812-1888). She has also written papers on authors including John Clare, John Keats, Charles Lamb, Andrew Lang, Mary Russell Mitford, the literary annuals, the Brontës’ Angrian fiction, and on the comic body in the long nineteenth century. She is particularly interested in writers who are also artists.