The Singing Turk explores the huge cultural phenomenon of European operas about Turks, flourishing especially during the eighteenth century, in the European age of Enlightenment. Though most people interested in opera are familiar with Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio, this was just one among hundreds of operas about Turks— most of them forgotten— which were staged all over Europe from the 1680s to the 1820s. The Singing Turk, first of all, attempts to recover the dimensions of this lost repertory— including works by Handel, Vivaldi, Rameau, Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, and Rossini, but also many other lesser known composers. While my research ranges around the opera houses of Europe, particularly important foci for me were the operatic centers of Venice, Milan, Vienna, and Paris.

The Ottoman empire was a great empire on three continents — including North Africa, the Middle East, and Southeastern Europe — and operas about Ottoman Turks in the eighteenth century were relevant to international relations; they were not just works of theatrical fantasy and entertainment. I try to place these operas in the context of European-Ottoman relations: relations of intermittent military warfare, but also of ongoing cultural and commercial exchange. I analyze how the figure of the singing Turk on the European stage illuminated certain issues that seemed particularly interesting to the enlightened European public — especially political issues concerning absolute rule, in the monarchical state and in the patriarchal family (or harem), but also issues concerning the control and display of extreme emotions in civilized society. Singing Turks on stage were seen and heard as the vocal avatars of absolute power and, at the same time, the emblematic voices of extreme emotion.

I’m interested in the ways that Ottoman Turkish instrumentation — especially “Janissary” percussion — was adapted to European orchestras for these operas, to mark their Turkishness, and I also study the special significance of the basso voice in expressing a sort of Turkish hyper-masculinity on stage. I explore how the singing Turk first came to the stage in the 1680s, immediately following the defeat of the Turkish army at the siege of Vienna in 1683. The Ottoman armies were then driven back into southeastern Europe, and this was the moment at which Ottoman power no longer seemed invincible, so that Turkish scenarios became plausibly entertaining on stage. I spend a significant part of the book reflecting on Rossini, the last great composer of “singing Turk” operas, and I’m especially interested in how Rossini’s Turks intersect with the Napoleonic and post-Napoleonic moment in Europe. Rossini’s Maometto Secondo, his daring opera about Mohammed the Conqueror, the Ottoman sultan who conquered Constantinople and toppled the Byzantine empire, was certainly also a post-mortem musical reflection on the Napoleonic project of continental conquest. Finally, I consider how the phenomenon of the singing Turk vanished from the European operatic repertory after the 1820s, such that the standard nineteenth-century repertory includes no singing Turks at all.

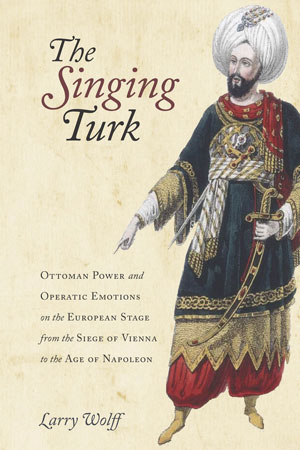

On the one hand, this book addresses the well-known literature on Orientalism, and argues that singing Turks were not understood as simply exotic “others” on the European stage. On the contrary, European audiences were supposed to recognize themselves in the singing Turks who addressed European issues of power and emotion, of relations between rulers and subjects and between men and women. At the same time, the book addresses Samuel Huntington’s idea of a “clash of civilizations” between the Muslim and Christian world, and I attempt to show that such a clash was decidedly not fundamental for the eighteenth-century world of the European Enlightenment. Even wearing their magnificent robes and dramatic moustaches, singing Turks were recognizably European in their characters and dilemmas, and European audiences responded to them accordingly, as figures with something to say about European issues and identities. Handel’s Sultan Bajezet (in the opera Tamerlano of 1724) had been conquered and defeated by Tamerlane, but the Ottoman sultan in captivity offered a model of Muslim Turkish pride and dignity — and served as a lesson in character for the European public.

This book emerges from a long commitment to trying to understand the cultural dimensions of East and West in European history, dating back to my research in the book Inventing Eastern Europe (1994). I argued in that book that Eastern Europe was liminally European, which made it seem both exotic and familiar at the same time. The figure of the singing Turk fundamentally illustrates this paradigm of simultaneous exoticism and familiarity. At the same time, The Singing Turk emerges from a broader attempt by historians to understand Europe’s relation to the Ottoman empire as not simply an oppositional encounter, but one of complex cultural encounter and exchange in Southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. I’m interested in the fact that both Vienna and Venice, the capitals of states neighboring the Ottoman empire (at the Habsburg Croatian frontier and the Venetian Dalmatian frontier) were also both opera capitals, and, therefore, Vienna and Venice were very important research sites for me.

Finally, I should say that, because of my role at NYU as director of the Center for European and Mediterranean Studies, I’ve been closely engaged while working on this book with the contemporary issue of Turkey’s relation to the European Union and the possibility (no longer likely) of eventual accession to the EU. This has, in turn, posed the question of Turkey’s historical and cultural relation to Europe, which the book partly explores, and this is of broader relevance for thinking about contemporary and historical encounters between Europe and the Muslim world.

If you opened the book to page 162 you would see a portrait print of Ludwig Fischer, the basso in Vienna for whom Mozart composed the great Turkish role of Osmin the pasha’s overseer. Osmin rages against the European foreigners and tries to obstruct the “abduction” from the seraglio, but he is finally dismissed by the magnanimous Turkish pasha at the finale, and thus prevented from taking his bloodthirsty vengeance against the European captives. It was the “bottomless deep” of Fischer’s low-notes that inspired Mozart to invest himself musically in the creation of this role, and, turning the page to 163, you’ll find me quoting Mozart’s long letter of 1781 in which the great composer reflected upon how Osmin’s extreme rage and ugly vengeful emotions could be contained within a musical structure that would still seem beautiful to the public. The Abduction from the Seraglio was actually the most popular of Mozart’s operas during his lifetime, precisely because it was written for a public that craved Turkish subjects; for Mozart it was his second effort at a Turkish opera, after the unfinished Zaide. And he would return to Turkishness again in Cosi fan tutte with the lovers comically disguised as Ottoman Albanians.

“A person who gets into such a rage oversteps all order, measure, and object,” wrote Mozart in the long letter to his father about Osmin. It was perhaps the most detailed letter he ever wrote analyzing the music of one of his own operatic characters. Music, of course, had to maintain order and measure in Mozart’s world of classical harmony, and Mozart himself was constantly trying to tame his own rages in real life. He was an angry young man in 1781, only 25 years old, and it was just then, in a rage, that he broke with his patron the Archbishop of Salzburg and began to try to support himself as an independent musician in Vienna, trying to please the public with operas like The Abduction from the Seraglio. On the following page, 165, I quote Mozart’s reference to “this stupid, coarse, and malicious Osmin,” but I argue in the book that Mozart really recognizes something of himself in Osmin, and that’s what makes the character so brilliantly human and helps to bridge the cultural divide between the Turkish and European characters in the opera. On page 166, I show a rare illustration of a costume design for Osmin, created for a production in Koblenz in 1787, and it shows clearly that for all his coarseness and comical malice, he was certainly a figure of some operatic dignity on the stage.

I’m eager to have readers think more deeply about the long history of how Europe has contemplated Turkey, and how the West has regarded the Islamic world. I want to encourage readers to consider how opera intersects with history and to think about musical issues as an important part of European cultural history — crossing the disciplinary lines that sometimes separate us as historians from our colleagues in the music department. I’d like to invite readers into a lost and largely forgotten world of musical and dramatic entertainments, and try to give a sense of their cultural and political meanings for people who would have been going to the opera in the eighteenth century. To give a sense of the music, I’ve also created a website that would allow readers to listen to relevant excerpts from the music of Singing Turk operas while they are reading my book. I hope that readers will find that a useful resource.

One great thing that we were able to do at NYU was to stage an academic symposium about the book, combined with the live performance of musical selections from the operas, and it’s also possible to have a look at the video and audio of that symposium.

Finally, I’m excited to see that some of these operas are being performed today. Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio is, of course, regularly performed, and I wrote about it in The New York Times when it was performed at the Metropolitan Opera in the spring of 2016. But I was also excited to see Il Turco in Italia (The Turk in Italy) performed in a brilliant production at the Rossini Pesaro festival in summer 2016, and Pesaro will produce two more Rossini operas from this tradition in summer 2017, La pietra del paragone and Le siège de Corinthe. I’d love it if my book contributed to a renewal of current interest in these fascinating works, which have a lot to offer for thinking about the Western relation to the Islamic world, including cultural encounters and mutual misunderstandings, back when these operas were composed and still today.

Larry Wolff is Julius Silver Professor of History at New York University and director of the NYU Center for European and Mediterranean Studies. He received his A.B. from Harvard and his Ph.D. from Stanford. Besides The Singing Turk, featured in his recent Rorotoko interview, and The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture, featured in an earlier Rorotoko interview, his books include Paolina’s Innocence: Child Abuse in Casanova’s Venice (2012), Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment (2001), Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment (1994), The Vatican and Poland in the Age of the Partitions (1988), and Postcards from the End of the World: Child Abuse in Freud’s Vienna (1988). Larry Wolff has received Fulbright, American Council of Learned Societies, and Guggenheim fellowships, and in 2003 was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.