The First Amendment says that “freedom of speech” shall not be abridged. The Supreme Court has said that the First Amendment unquestionably covers Jackson Pollock’s paintings, Arnold Schoenberg’s music, and Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky.” Why do these forms of expression get constitutional protection? The paintings and the music aren’t “speech” at all, and nonsense is basically a string of meaningless sounds. So, the Constitution’s text can’t give us the answer.

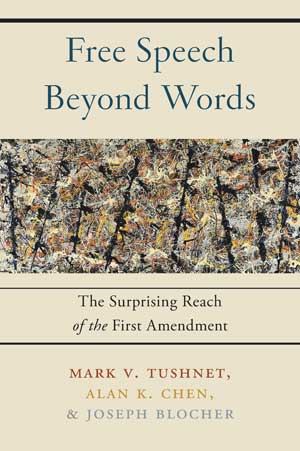

Professors Blocher, Chen, and I tried to figure out that answer in Free Speech Beyond Words, and, to our surprise, we found that providing the answer is harder than most people think. We look at constitutional doctrine, academic theories seeking to explain why the Constitution protects free speech, and philosophical accounts of meaning. We examine those theories to see whether they apply to art, instrumental music, and nonsense.

The Supreme Court is clear about its conclusion that those things are covered by the First Amendment. The doctrines it deploys in First Amendment cases, though, really don’t support that conclusion. Or, at least, they don’t support that conclusion without a fair amount of tugging and hauling. The Chapter on abstract art grapples with these doctrinal problems.

The chapter on instrumental music deals with theories of the First Amendment. One prominent theory says that free speech is protected because it allows us to discover truth – factual, moral, or political. But it’s hard to see how looking at an abstract painting or listening to a Beethoven string quartet leads to the discovery of truth. Or, at least, it’s hard to see how those activities have that effect any more than a host of other activities – running a small business, for example – would. But of course we have no serious problems – and certainly no First Amendment problems – with a host of business regulations.

Another prominent theory seems more promising. Artistic activities are expressions of a person’s autonomy, and freedom of speech is often defended because expression is one of the ways people use to be themselves. Here too the problem is that lots of other activities – again, running a small business is an example – are ways people express themselves.

Free speech is important for making sure our government is truly democratic: If you can’t criticize the government, how can we ever change the direction our nation is moving? But, again, the connection between democratic self-government and abstract art, instrumental music, and nonsense turns out to be really hard to figure out.

Chapter Three connects nonsense to several philosophical accounts of meaning – and meaninglessness. It suggests that we have come to understand the word “speech” to encompass nonsense. Once we do, that social understanding properly informs how we apply “speech” in practice.

In the end, we don’t disagree with the Court’s conclusion. We do devote some space to ask whether other forms of expression – artistic dance, sports like mixed martial arts, cooking with unique recipes, designing parks, and more – should be covered by the First Amendment. Our primary goal, though, is to show that the answer to the question “Why does the First Amendment cover art, music, and nonsense” is easy, but that defending the answer is quite difficult.

Our questions here are not terribly practical ones in the United States. No one really advocates for regulating art or music as such. True, Nazi Germany did suppress “degenerate” art and music – abstract art and jazz – and the former Soviet Union suppressed abstract art in favor of “socialist realism.” But we don’t think that anything similar is likely in the United States. (Sometimes questions do come up about whether the government can refuse to support some kinds of art that it couldn’t suppress, but those questions are different from the ones we deal with.)

We got to thinking about these questions because we were puzzled about constitutional doctrine and theory. Often we don’t know what the answer to a constitutional question is, and try to figure out what doctrine and theory tell us about the answer. A current example: Does President Trump’s receipt of income from payments to his hotels from foreigners violate the Constitution’s Emoluments Clause? Lawyers look to doctrine, practice, and theory to come up with an answer.

Here, though, we know the answer from the beginning – of course the First Amendment protects these works. But getting from doctrine and theory to that answer turns out to be tricky – sometimes, trickier than coming up with an answer about the Emoluments Clause.

That fact was, for us, an intriguing one. We think that explaining why some easy answers have complicated explanations illuminates broader themes in constitutional law. For example, sometimes we might come up with a complicated rule that tracks the Constitution’s words and purposes pretty well, but the rule is quite complicated. Sometimes it’s better to have a simple rule that occasionally produces results that aren’t easily defended if you look at why we have the rule. And sometimes it’s a bad idea to adopt an approach that requires judges to do a lot of analytic work to get to a result they know is right even before they start thinking about the problem.

We use the peculiar problems of “free speech beyond words” to get us looking at the big picture, which is: How should we think about constitutional doctrine, both the First Amendment and the rest of the document?

We think that the book’s cover is a terrific “provocation” for thinking about the problem. We hope that readers (viewers?) will ask themselves, “Why is this covered by the First Amendment?” Chapter Two, on abstract art, has a bunch of illustrations, and their point, mostly, is to provoke the same question. We wanted to do something similar for the chapter on instrumental music, but it’s a physical book, not an electronic one. So the best we could do it direct readers to sites – mostly on YouTube – where they can listen to the music we talk about. Here are a couple of examples: Tuvan throat singing and a performance by the Dave Brubeck Quartet. And, in the chapter on nonsense, we remind readers of the “lyrics” to “ I Am the Walrus,” “Who Put the Bomp,” and “Louie Louie,” which we suggest are, or are nearly, gibberish.

The point of all this is to motivate the book’s larger concern: Of course all this stuff is protected by the First Amendment, but why?

First of all, I want to recognize here my two co-authors. Even though the responses in this interview are mine only, I believe to speak on their behalf as well. Joseph Blocher, who is a professor of constitutional law at Duke, once clerked for Judge Guido Calabresi, one of the nation’s most creative legal thinkers. Alan Chen, who is a professor of constitutional law at the University of Denver, has eminently represented civil rights plaintiffs in California, Idaho and Utah.

Second, we want to get people thinking about questions that might never have occurred to them. Or, more strongly, we want to get people thinking about the “obvious” answer they would give to the question of why Jackson Pollock’s paintings, Arnold Schoenberg’s music, and “Jabberwocky” are covered by the First Amendment. Once they do, maybe they’ll think about other topics, like the coverage of dance, sports, gardening, and cuisine. But, frankly, I think we’d all be completely satisfied if readers found that our arguments unsettled their intuitive answers, at least for a while.

Mark Tushnet has been teaching constitutional law for several decades, specializing over the past decade or so on the First Amendment and comparative constitutional law. He was a law clerk to Justice Thurgood Marshall, and was an important contributor to the development of “critical legal studies,” a skeptical approach to common ideas about what law is and does.