In “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863) Charles Baudelaire writes about the great “operatic shores of the Bosporus.” More recently Orhan Pamuk reflects with melancholy on Istanbul’s former multiethnic vibrancy in the nineteenth century. Istanbul Exchanges, too, is inspired by the Ottoman capital and its cosmopolitan artistic milieu in that century. The cultural exchanges that occurred in the city cannot be contained by a narrow national history of Turkish art because the players within these art circles were far more diverse. Nor is this cultural geography explicable through a polarized theory of Orientalism where we simply address Europe’s representation of cultures of the Islamic world.

Few of us think of Istanbul when we recall Baudelaire’s famous essay of 1863 and yet the city is at the heart of Baudelaire’s lyrical paean to nineteenth-century modernity. In the Istanbul sketches of Constantin Guys, Baudelaire found signs of modernity in contingent details that conveyed a disjunctive encounter between East and West. The cosmopolitan Ottoman capital may have been occluded from histories of nineteenth-century modern art in our own time, yet Istanbul, like Paris, was one of Baudelaire’s key sites of modernity.

Baudelaire didn’t write about Ottoman art, yet Paris-trained Osman Hamdi Bey was a painter of modern life whose work resonates with Charles Baudelaire’s formulations about contemporary art. Osman Hamdi’s painting, Women in Feraces, 1887, is but one of many works by European-trained Ottoman painters discussed in my book that challenge us to think about the modernity of this art. This painting renders the public space of Istanbul as a site of modernity through the hybrid fashions of elite Ottoman women. The contours of the bustle, an index of modishness in international women’s fashion, are evident underneath the ferace, and translucent face veils are modishly combined with matching and contrasting parasols. The beauty of this fashion pageant, that mixes eastern and western influences, is conveyed through the syncopated rhythms of colour as the eye moves laterally across the surface of Osman Hamdi’s painting. This is not a timeless orient – it’s a quintessentially modern spectacle.

The cultural traffic between Istanbul and Paris is but one of the geographic vectors that my book analyses. Webs of art and patronage connected Istanbul to numerous art circles across Western Europe; they operated between the capital and other cities within the Ottoman Empire and also encompassed links between minority Armenian communities in Istanbul and within the Russian Empire in the Caucasus. Mapping these diverse networks of artistic exchange has presented a particular research challenge. The patterns of movement over the century resulted in a centrifugal distribution of artworks and documents from Istanbul to archives, museums, and private collections in Poland, Armenia, Denmark, Italy, France, England, and Turkey. I hope the reader will derive pleasure from many of these works of art that are drawn together for the first time and perhaps be surprised by the complex narratives of their cross-cultural production and reception.

There has been much debate over the last decade about expanding our discipline to create a global history of art, but what precisely are the new methods and protocols for writing these more encompassing transcultural histories? It has long been my conviction that Istanbul and its cross-cultural webs of art and patronage have much to tell us about a global history.

In this book I propose a network model for understanding these interconnections. Istanbul was a context where European artists were working alongside Muslim and Non-Muslim Ottomans. Many artistic initiatives received patronage from both foreign diplomatic communities and the Ottoman court. This book attends to these patterns and processes of transcultural artistic exchange. Tracking Istanbul’s multi-sited and multi-directional art connections discloses the nodes and vectors that register the particularities of Istanbul as a place of cross-cultural contact while also situating Istanbul’s exchanges within a global history.

This is a history of art attuned to patterns of artistic exchange that accounts for the movement of art works in and out of Istanbul and its changing meaning on the move. Art produced in this context was created, apprehended and interpreted within a cross-cultural web of meanings. Sometimes this web was a battlefield of competing representations, at other times it was a negotiated matrix of divergent positions. Such cross-cultural transmission was also entangled within patterns of misinterpretation, as visual forms were created, reshaped, censored, or productively misunderstood. This served to produce divergent forms of agency of art works and artists.

In this book I characterize transcultural artworks as “networked objects.” The Young Album analysed in chapter one exemplifies this concept. This album, a history of the sultanate through portraiture, was the single most influential visual codification of the Ottoman dynastic image in the nineteenth century. Commissioned by Sultan Selim III in 1806, it was originally intended as a gift in Ottoman-European diplomatic exchange relations, but the album had a much more unstable history across the century as it shuttled back and forth between Istanbul and London.

As part of this historical mobility there were multiple shifts in the Young Album’s image economy: from diplomatic gift culture to consumer culture and from luxury album to intimate cartes de visite. In these different iterations it was variously co-opted for Ottoman and British versions of the Empire’s history. Through processes of supplementation with additional text and images rupturing the aesthetic coherence of the original Ottoman commission, the cultural boundaries of this work of art were redrawn. Divergent centers of power were imputed, as different forms of authorship were claimed, conflicting versions of Ottoman history were inscribed, and alternate audiences were engaged. Through this durational case study, cultural encounter emerges as a procedure entailing multiple transformations and multiple local effects.

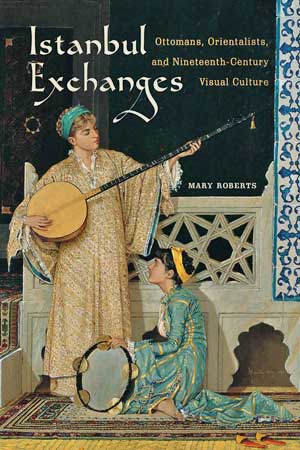

Istanbul Exchanges builds on ideas developed in my book, Intimate Outsiders: The Harem in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman and Orientalist Art and Travel Literature (Duke University Press, 2007). I engaged debates on gender and Orientalism through a study of representations of the harem by Orientalist artists, women travel writers, and it was the first study of elite Ottoman women who commissioned their own portraits. I characterized artist’s embedded in foreign cultures as Intimate Outsiders, coining this term to characterize the forms of privileged access of European women to Ottoman culture, as well as the familiarity of elite Ottoman women with European art in this period of Ottoman modernization. I emphasized the sustained tension between intimacy and outsideness in this term as a model for understanding artistic production in a cross-cultural context.

I hope a reader who stumbles across this book might initially be drawn to the visual richness of this art and then engaged by their cross-cultural narratives. These images are drawn from internationally diverse sources; finding them has been an adventure. When I first began travelling to Istanbul, many of these paintings were in obscure corners of the former Ottoman palaces on the Bosphorus, and many were uncatalogued. It is my conviction that drawing together this visual archive, that will come to form part of a new canon of a global history of nineteenth-century art, can challenge our theoretical presuppositions about cultural production in this period.

The one artwork that is likely to be familiar to readers is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer. This painting takes us to the heartland of the Orientalism debate. It was made famous (or more perhaps more accurately, it became notorious) when reproduced on the cover of Edward Said’s seminal book, Orientalism in 1978. Since then Gérôme’s work has come to exemplify the binary logic of the European discourse through which Western visual culture produced the East as its other. My book disrupts these entrenched understandings of Gérôme’s art by resituating his orientalism within a broader reception history, encompassing international networks of pedagogy and Ottoman patronage.

Gérôme’s works were among the contemporary art that Sultan Abdülaziz and his aide-de-camp (Gérôme’s former student), Şeker Ahmed Paşa, purchased for the Ottoman palace through the French dealers Goupil et Cie in the 1870s. Contextual analysis of these works enables us to consider what they meant to an Ottoman audience and to situate these collecting practices within the semantic economy of Goupil’s international networks of image replication and circulation.

The acquisition of Gérôme’s paintings for the Ottoman palace reveals the mutable semiotics of his Orientalism. Among an elite Ottoman audience in Istanbul they were transmuted into Ottoman Orientalism. One of these paintings, generically titled Bashi-Bazouk Dancing, was renamed in Istanbul. Ottoman viewers recognized it as a representation of the distinctive costume and dance of the Zeybek warriors from the mountain regions of Western Anatolia. They had been part of the irregular Ottoman forces and their itinerant existence and distinctive traditional dress was the antithesis of Ottoman palace life governed by formality and protocol. Indeed the range of representations of Ottoman culture within the sultans’ art collection, which by the end of the century came to include numerous paintings of Arab horsemen from the empire’s peripheries, provided a visual précis of the empire’s diversity for its elite audience. As such they were a reminder of cultural patrimony – that which distinguished the Ottoman Empire from Europe – within the contextualizing frame of the modern Ottoman palace.

In 1878 Gerome borrowed his Zeybek painting back from the Ottomans in order to display it in the Paris International Exposition. So too, the painting was reproduced as a print that circulated widely across Europe and America. In these contexts the Ottoman warriors took on more exotic, Orientalist connotations. By tracking the circulation of this painting from Paris to Istanbul to Paris and then back again, the life of their reprographic double, and the variant titles that this painting accrued as a result of these transitions, my study exposes a complex range of meanings for divergent audiences.

This broader cross-cultural interpretive work reveals a more entangled politics of spectatorship for Gérôme’s Orientalism than Linda Nochlin’s formulation about his art that, “The white man, the Westerner, [exerts] … the controlling gaze, the gaze which brings the Oriental world into being, the gaze for which it was ultimately intended.”

If we approach this distinct context without critically analysing the appropriateness of the art historical tools we are using we risk replicating a narrative of this modern art beyond the Western European cultural capitals as derivative and belated. Accordingly, in Istanbul Exchanges I propose a shift in emphasis from institutions to networks.

Over the last three and a half decades the social history of nineteenth-century French and British art has developed a reception theory premised upon the large and centrally organized art institutional structures of the Royal Academy and the Salon. Whether artists based in these Western European cities sought to be embraced by these academic institutions or defined their practice as part of an avant-garde that rejected such structures, the institutions of the Salon and Academy remained the most powerful defining features of that art milieu.

In Istanbul a different situation prevailed. Art circulated within linguistically and culturally diverse local, foreign, and expatriate communities. It could be seen in the Ottoman palaces, foreign embassies and Christian churches, as well as in the homes of the Ottoman elites, the expatriates, and Levantines. It was taught in private studios in Pera run by European-trained foreigners, in the Ottoman military academy, and in select government and minority community schools.

In the 1870s and 1880s, reports and reviews of art exhibitions appeared in local Ottoman, expatriate, and Armenian newspapers, and yet, like the exhibitions themselves, this art writing was sporadic and unsystematic. There was no extensive art-critical press in Istanbul, unlike in London and Paris, where a culture of regular reviews sustained a broader bourgeois public for art. The audience for art in Istanbul in this period is more divergent and disparate than in the Western European capitals, thus compounding the challenge of providing a precise definition of the public for art in this city.

My analysis of Istanbul’s art exhibitions reveals contested definitions of Ottoman and Orientalist cultural identity. These exhibitions have been absent from the lively debates within the Anglo-American academy about nineteenth-century exhibition culture. Unlike the annual exhibitions at the European art academies and the international exhibitions held around the globe, Istanbul’s art exhibitions were without institutional infrastructure or significant international profile. But the very cause of their marginality, I argue, is also the source of their revisionary potential.

The inclusion of Ottoman artists distinguishes these exhibitions from societies of Orientalist painting in Europe. These provisional and loosely structured collaborations encompassed overlapping societies and audiences with a range of agendas and national affiliations. Their diverse agendas distinguish them from official Ottoman displays at the European World’s Fairs and Istanbul’s state-sponsored museums. Reviews of the Istanbul exhibitions published in Istanbul, London, Copenhagen, and Tiflis discloses remnant gossamer threads of intersecting networks within diverse local communities and the links between them and the art world internationally. At times these networks were divided along the fault lines of national allegiance in response to contemporary political debates, but a study of these exhibitions also reveals the sense of multiple belonging of many of Istanbul’s artists (especially those who were members of Ottoman minority communities). A study of their fraught critical reception in Istanbul provides unique insights into the varied ways cross-cultural collaboration was imagined, interpreted and contested.

Mary Roberts, Robert Sterling Clark Visiting Professor in Art History, Williams College and Professor of Art History, University of Sydney, was awarded the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand’s Book Prize for Istanbul Exchanges. She is a leading figure in Orientalist and Ottoman art studies, with particular expertise in the art and culture of travel. Her first book was Intimate Outsiders: The Harem in Ottoman and Orientalist Art and Travel Literature. She has co-edited four other books and has received numerous awards and fellowships. Her next book is on Artists as Collectors of Islamic Art.