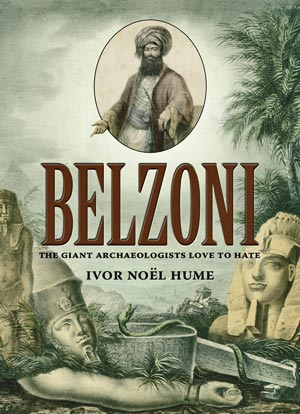

Giovanni Batista Belzoni was a towering figure at the beginning of archaeology in Egypt, not for his recognized talents but for his 6’6” height.

Nearly 200 years later he is still despised by archaeologists who see him as a looter and vandal. That he recovered some of the British Museum’s largest and heaviest Egyptian treasures and successfully shipped them down the Nile using only papyrus ropes and a few poles, has largely been ignored. Instead, his sponsor in Egypt, Consul Henry Salt, took most of the credit until he, too, was vilified by his scholarly peers.

Born in Padua in 1778 and trained in Rome as a hydraulic engineer, in 1803 Belzoni arrived in England with skills nobody needed. He therefore earned a living as a circus giant and strong man, playing in theaters and fairgrounds to uneducated and sometimes derisive crowds.

The story of Belzoni’s ten years in Britain was a profitable embarrassment. Though somewhat embellished by Charles Dickens, it was through the novelist’s eyes that we meet Sarah Barre who had become Belzoni’s wife soon after his arrival in London. She has been said to have been a fairground balancing act, a rope dancer, but later with Belzoni in Egypt she showed herself to be both an artist and a writer. Indeed, the farce and drama of Belzoni’s short life became the tragedy of Sarah’s prolonged widowhood.

In this book, therefore, Sarah’s loyalty to her not always considerate husband, coupled with her prolonged efforts to keep his fading memory alive, becomes an integral part of the story.

One might wonder why a twenty-first century reader should want to delve into a biography of someone so distant and so out of tune with the modern world.

At one level it provides escapism at its dramatic best, but at another it weaves a tale as complex as a novel by Henry James. In the end one realizes that the greed, jealousies, snobberies of academics, distrust of foreigners, and the desire to be accepted and honored are as alive today as they were in 1823 when Giovanni Belzoni died alone and forgotten in the Benin jungle of West Africa.

I am often asked what drew me to Belzoni. Although I am no giant, we had something in common. I spent four years in the British theater before turning to archaeology, a profession for which I had no previous experience and so was vilified by academic critics. In essence, therefore, I was a short Belzoni.

In the course of what proved a long and successful career my archaeologist wife Audrey (not Sarah) and I traveled three times up and down the Nile. Each time we found the name Belzoni carved onto columns and into frescos. Simple curiosity made us want to know and understand a man who would do something so destructive.

It turned out that Belzoni was only adding to generations of scribes who felt impelled to put their stamp on the past. Beginning in the fourth century B.C. Greek mercenaries were followed by Romans, Coptic Christians, French and British soldiers, countless 19th century tourists and eventually a Soviet dam-building engineer. In short, Belzoni merely did what others had done before him.

Belzoni was not only a graffitist but also an artist of considerable talent who in the space of three years assembled a folio of drawings that rivaled those of Napoleon’s military artist Dominique Denon. In 1820 Belzoni published his work to illustrate the book that was to be his enduring cenotaph. I was able to buy both and resolved, one day, to republish examples of his hand-colored lithographs. But as Belzoni himself knew, the illustrations meant little without his narrative—which therefore remains the cornerstone of this book.

Every story needs a villain and Belzoni had his in the person of French Consul Bernardino Drovetti who was treasure hunting for France while Salt was collecting for the British Museum. Caught in the middle, Belzoni narrowly escaped being murdered by Drovetti’s men amid the ruins of Karnak (Luxor).

When Belzoni sat down to draw the Karnak temple, he was awed by the scale of the ruins. Today, partially reconstructed, its great hypostyle hall is even more breathtaking. As I have told many a student, until you have stood amid the columns of Karnak you have no yardstick against which to judge the achievements of the human race. Without iron tools or computer-aided projections the Egyptians turned monumental ideas into glorious reality.

Opening my book to pages 64 and 65, you will sit beside Belzoni as he drew the tumbled wonders of Karnak. It is a safe bet that having done so, like him, you will want to keep on digging—while watching for the shadow of a Drovetti lurking behind the next pillar.

Belzoni was the first man to open the great temple at Abu Simbel and to discover the entrance to the second pyramid at Giza. It is my hope that as soon as the Arab Spring turns to peaceful summer my readers will be booking visits to the Nile—remembering, of course, that memorializing one’s presence with a knife or chisel provides an opportunity to experience the pyramid-like solitude of an Egyptian jail.

Born in England in 1927 the author became an archaeologist charged with saving the buried relics of bombed London. Seven years later he accepted the post of archaeological director at Colonial Williamsburg and remained there until his retirement in 1987. His first books were published while he was still in London, and thirteen more have followed, interspersing historical fiction with Virginia history and archaeology. His play about Virginia colonist John Smith ran in Williamsburg throughout its 400th Anniversary and his television programs have won international awards. Throughout his career Hume has been a well-known lecturer at museums, in academic halls, and the theater of the National Geographic Society. He devoted one of his Washington lectures to the history of Egyptian graffiti.