There are plans in the works for a multiracial film version of Macbeth. Like the famous 1936 production that Orson Welles directed in Harlem, this adaptation is to be set in the Caribbean. Yet neither the Hollywood movie nor the Welles stage production are the first Macbeths to find the play unusually well-suited to American racial discourse.

Macbeth was the first play documented in the American colonies, held by a plantation owner in 1699 Virginia. Many 19th century abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, called upon Macbeth in their speeches. Artists ranging from Langston Hughes to Duke Ellington to Suzan Lori-Parks invoke it in their work. What exactly is it about Macbeth that’s so conducive to discussions about race in the United States?

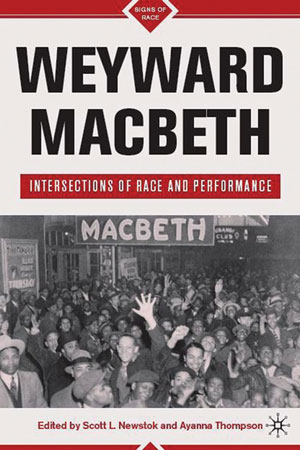

Weyward Macbeth is a collection of two dozen essays that explore this topic. We co-edited the book based on a conference held at Rhodes College in 2008.

Why did we use that strange word “weyward” in our title? That’s the original spelling of the “weird sisters,” or witches, in the first edition of Shakespeare’s play, from 1623. And we think “weyward” aptly captures some of the peculiar dynamics of this drama.

On first glance, the intersections of race and performance in Macbeth might seem arbitrary.

Yet there remains something unique about Macbeth: it’s the haunted play, with the title you’re not supposed to name in a theatre. (Recall the minor hubbub when President Obama cited Lincoln’s fascination Macbeth at the February 11, 2009 re-opening of Ford’s Theater.)

Macbeth is the drama in which “nothing is / But what is not.” Macbeth is anomalous and different—”Other,” to use the lingo of literature scholars. At its core, the “Scottish play” is about the distinctions between a king and one who wears “borrowed robes.” Should we be surprised that Macbeth is not the antithesis of a “race” play?

“Macbeth subtly lures you into thinking that the ‘Scottish play’ doesn’t carry ‘the onerous burden of race,’ as the actor Harry Lennix puts it. This lure is so powerful that actors, directors, and writers often assume that they are the first to see the connections.”

While Macbeth may not fit neatly into the category of a “race” play, like a specter it is nevertheless haunted by, and haunts, the language and performances of race.

Othello, in contrast, plays something of an over-determined role in historical and contemporary constructions of racial difference; one reviewer of Paul Robeson’s performance in 1944 even went so far as to call it “Shakespeare’s American play.”

Macbeth subtly lures you into thinking that the “Scottish play” doesn’t carry “the onerous burden of race,” as the actor Harry Lennix puts it. This lure is so powerful that actors, directors, and writers often assume that they are the first to see the connections.

To the contrary, Macbeth has long played a role in American constructions of race. Orson Welles’s 1936 Federal Theatre Project (FTP) production of Macbeth—commonly referred to as the “Voodoo” Macbeth—is often discussed as the innovation of Welles’s singular and immense creative genius. But there was an all-black FTP production the year before in Boston—as well as a number of amateur productions in previous decades.

Likewise, starting in the 1970s and continuing to this day, many contemporary theatre companies repeatedly assume that they are the first to re-stage Welles’s “Voodoo” version. But several African-American, Asian-American, Native American (Alaskan and Hawai’ian), and Latino theatre companies have turned to Macbeth to help stage their own unique racial, ethnic, and cultural identities.

Macbeth’s appeal—that it lacks “the onerous burden of race”—comes at a price. Despite the fact that many of the non-traditionally cast productions bill themselves as unique translations—the first to change Scotland to the Caribbean, “Africa,” an urban ghetto, a multi-racial post-apocalyptic future, and so on—they can only do so by employing a type of historical amnesia.

That is the play’s true magic, and perhaps its curse as well. Could anything be more Shakespearean and American?

So that we might learn what it means to remember one facet of our cultural legacy, we include in the book some two dozen concise essays addressing everything from Frederick Douglass’ allusions to the play, to hip-hop adaptations on YouTube, to Duke Ellington’s revisionary musical rendition, to multiracial prison productions.

In addition to chapters we submitted as co-editors, over two dozen contributors include: Celia R. Daileader, Heather S. Nathans, John C. Briggs, Bernth Lindfors, Joyce Green MacDonald, Nick Moschovakis, Lisa N. Simmons, Marguerite Rippy, Lenwood Sloan, Harry J. Lennix, Alexander C. Y. Huang, Anita Maynard-Losh, José A. Esquea, William C. Carroll, Wallace McClain Cheatham, Douglas Lanier, Todd Landon Barnes, Francesca Royster, Courtney Lehmann, Amy Scott-Douglass, Charita Gainey-O’Toole, Elizabeth Alexander, Philip C. Kolin, Peter Erickson, Richard Burt, and Brent Butgereit.

As the collection is designed to combat the historical amnesia about this play’s weyward history within dialogues about race, we also include an appendix of non-traditionally cast productions. Although it is impossible to catalogue every performance (even if one focuses primarily on professional productions in the United States), the 100 productions featured in this appendix reveal how often producers, directors, actors, and reviewers imagine themselves working in a vacuum.

Documenting the frequency of these productions and analyzing the adaptations, appropriations, and allusions, Weyward Macbeth positions the “Scottish Play” in the center of American racial constructions. Shakespeareans alone could not tell this eclectic story: we needed Americanists, filmmakers, musicians, musicologists, actors, directors, and artists to tell a tale that signifies something about Macbeth, race, and the American imagination from as many viewpoints as possible.

“Macbeth focuses on the indelible quality of blood,that smelling substance that Lady Macbeth can’t fully wash from her hands.This unnervingly coincides with early American debates about the so-called nature—or essence—of race.”

Macbeth’s insistent language of blood and staining seeps into American racial rhetoric. Macbeth focuses on the indelible quality of blood, that smelling substance that Lady Macbeth can’t fully wash from her hands.

This unnervingly coincides with early American debates about the nature—the essence—of race. On the one hand (excuse the pun), the proponents of slavery (and later segregation) insist that the blood is the thing: the essential, internal substance that marks races, even down to a single drop. On the other hand, many opponents of slavery (and later segregation) quote passages about blood from Macbeth in their protest speeches: the external mark that stains America’s formation and history.

We feel that the very weyward qualities—in all of their myriad complexities—of Shakespeare’s playtext, its performance history, and the critical scholarship must be brought into focus so that our desires for progressive acts are not disabled before they even begin. A conscious remembering, revisioning, and restaging is the true first step to change and progress.

SCOTT L. NEWSTOK is Associate Professor of English at Rhodes College, where he organized the 2008 symposium on Macbeth and African-American culture. He has edited Kenneth Burke on Shakespeare (2007), and has published a study of the rhetoric of English epitaphs, Quoting Death in Early Modern England: The Poetics of Epitaphs Beyond the Tomb (Palgrave, 2009). AYANNA THOMPSON is Associate Professor of English, and an affiliate faculty in Women & Gender Studies and Film & Media Studies at Arizona State University. She is author of Performing Race and Torture on the Early Modern Stage (2008), and the editor of Colorblind Shakespeare: New Perspectives on Race and Performance (2006). Her new book on Shakespeare and race, called Passing Strange, is forthcoming from Oxford.