Fashioning Faces, a cross-disciplinary study, looks at how literary and visual portraiture in the British Romantic era embodied a newly commercial culture.

I consider the Romantic era as a transitional period characterized by a pre-modernist focus on identity formation and legibility. The widespread cultural shift toward a world of faces and figures foreshadows today’s world of increasingly available self-reflections and depictions.

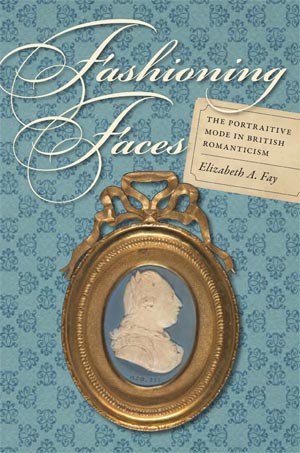

So I invented the term “portraitive mode” to describe a diversity of cultural and material expressions of identity—visual and verbal portraits, miniatures, poetry, collections, caricatures, and biographical dictionaries.

The book integrates portraiture within broader cultural currents such as fashion and consumption, the rise of celebrity culture, collecting and house museums, and travel literature.

My focus is on synthesizing different kinds of material—tying together diverse artistic, literary, and cultural modes to shed new light on the historical significance of portraits and the centrality of Romantic portraiture as a vehicle for expression and subjective exploration.

An important aspect of the book is its examination of individuals who contributed to this phenomenon in innovative ways, or who exemplified the portraitive reflex.

Josiah Wedgwood, for instance, took great care to create chinaware that would reflect consumers’ conception of British character, and in the process established his own character and self-portrayal as the “face” of British table services. Sir John Soane, the architect, designed his house museum as a self-portrait, particularly rooms such as his Gothic parlor that contain biographical references; he “published” this self-portrayal by making his museum open to the public. Mary Robinson and Lord Byron used their popular personae to dramatize self-portraits that could enhance their literary careers and fame.

Many of the techniques pioneered in this period for creating self-portraits, manipulating public exposure, and combining biographical and pictorial portrayals are ones still in use in today’s self-conscious culture.

“Twentieth-century American popular culture figures like Andy Warhol, the Rolling Stones, and Madonna have their analogues in figures like Richard Cosway, Beau Brummel, Lord Byron, and Mary Robinson.”

Fashioning Faces begins with the assumption that cultural history as an approach and a methodology can capture a cultural phenomenon such as the Romantic fascination with biography and portraiture more accurately than standard histories.

Cultural history is cross disciplinary, meaning that it assumes that a range of disciplinary approaches and perspectives will be necessary to engage the larger questions arising from the object of study. In this instance, standard histories of portraiture don’t usually consider the close association of biography and portraits—e.g., how in literary portraits these are in a metaphorical sense the same thing. Similarly, studies of biography don’t consider how portrait cameos and buttons are narratives of the self.

Books on portraiture don’t usually take into account china sets, uses of portraits in novels, biographical dictionaries, house museums, or how a miniaturist like Richard Cosway could use portraits of others to create an intricate portrayal of himself.

Histories of consumer culture are not likely to consider how Wedgwood’s gigantic dinner service for Catherine the Great is a portrait of British character made for export, and very similar to landscape “portraits” of the period.

And histories of fashion don’t use their information about the rapid shifts in fashion to consider how this allowed people to constantly adjust their self-portrayal to others, and therefore to subtly (or not so subtly) to change their character.

We know that new character types were invented during the Romantic period—the dandy is a well known example of this—but not as much about how people used these new types to modulate their own personae and play with their self-portrayal even within the context of the traditional “sincere” character.

I began the project by sheer chance, when browsing through second hand bookstores and becoming fascinated by old “portraits of the age” volumes such as those by Sainte-Beuve. Then I started to notice all the references to portraits, portrait lockets, and miniatures in the novels, plays and poems I teach in my courses on British Romantic literature.

I also noticed portrait lockets and other jewelry in society portraits of the day, and then became fascinated by studies of consumerism during the period. I began to think about how today we collect objects in order to fashion a self-portrait that is meant both for our own enjoyment and to show to others.

Eventually I realized that twentieth-century American popular culture figures like Andy Warhol, the Rolling Stones, and Madonna have their analogues in figures like Richard Cosway, Beau Brummel, Lord Byron, and Mary Robinson.

Toward the end of the second chapter I discuss William Hazlitt’s Spirit of the Age. For me, this section embodies all the concepts I try to engage in the book.

I look at how Hazlitt consciously uses biographical sketches of exemplary literary figures to reveal the character of the Romantic era; how his own theory of what he is accomplishing in those sketches anticipates twentieth-century theories of identity in consumer culture; and how writers’ own self-portrayals could be used against them by an expert portrait artist.

The fact that Hazlitt first trained as a portrait painter underscores how his Spirit of the Age so consciously engages the current fascination with portraiture. My favorite essay is the one on Jeremy Bentham in which Hazlitt describes Bentham’s “mechanical” theories of social control so as to portray Bentham himself as mechanical, a kind of kooky clock whose mechanisms are a bit askew.

I’m also very fond of the sections on Horace Walpole’s playhouse, Strawberry Hill. Here he created a fanciful self-portrait that was open to the public and for which he wrote a guidebook. The different rooms in the house parody rooms in Elizabethan-era estates, mocking the chivalric codes of those stately homes, and at the same time tantalizingly tease the visitor about Walpole’s own homosexual identity. Walpole’s extraordinary sense of fashion and willingness to combine authentic and valuable works of art with paper mache and faceted mirrors to imitate real Gothic interior décor allowed him to create an extraordinary architectural self-portrait.

At the same time, I would also direct a reader to the first chapter, where I lay out the book project and some of its main ideas and explain how theories of consumer culture can be very helpful for understanding how fashion and portraiture go hand-in-hand when consumption rather than tradition or family inheritance rule people’s sense of the everyday world.

“But how did this modern identity-play come about? And why are we both so facile at it today and so uncomfortable when public figures like politicians employ it?”

I would hope that a reader would take my study and use it to think about how we portray ourselves—our characters, and our social identities—today.

We understand today that identity is not stable, and that we all experience a variety—or palette—of identities depending on what we’re doing and who we’re with. At the office, in a subway, at the grocery store, cleaning the house, walking on a crowded street, chaperoning children through a museum: these are all moments when we take on specific public or private identities both for ourselves (maybe in order to focus on a task) and for others (to persuade others that we’re serious, competent, in charge, knowledgeable, etc.).

But how did this modern identity-play come about? And why are we both so facile at it today and so uncomfortable when public figures like politicians employ it? What are the social circumstances surrounding our own fascination with identity portrayal? And why do we think portraits of the body and especially the face can contain a “truthful” portrayal? What secrets of the individual character do we think portraiture and biography (verbal portraits) can reveal?

Thinking historically about these questions can help us understand public posturing, group identity, group defensiveness, shifts in public personae—that kind of identity posturing that can be very sincere even when playful or quickly changing.

Elizabeth Fay is a Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is also Director of UMass Boston’s Research Center for Urban Cultural History. Specializing on British Romantic Literature, she has written books on William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Romantic Medievalism, and feminist approaches to British Romanticism. For several years she has also served as co-editor of Literature Compass Romanticism, an ejournal published by Wiley/Blackwell, and has co-edited an edition of Felicia Hemans’ Siege of Valencia.