Camps are unavoidable functions of our contemporary moment, registering local and global forces at their earliest stages and thus signaling trend, crisis, and identity. These malleable spaces conform to our desires but might equally be constrained or manipulated by external forces. Some camp to escape, while others set up camp to approximate return to a home that is inaccessible or does not exist, still others are forced to camp. This functional range is unprecedented.

Protestors. Artists. Boondockers. Dreamers. Survivalists. Hackers. Detainees. Refugees…. The book covers a lot of ground – from festival camps to disaster relief camps to man camps. I have sought to make sense out of this vast network of provisional and semi-permanent sites with a guide that affords opportunities to “see” situations that are far and near, fleeting and fixed. The book design underscores this immediacy and utility with open binding and simple paper stock, recalling both tourist handbook and military manual.

I have also sought to tell the story of camps – their full range of experiences and conditions and the forces that shape them. Each type of camp becomes a story within larger global narratives of autonomy, control, and necessity – categories that correspond to the book’s three parts. “Autonomy” focuses on camps of choice, “control” investigates camps regulated by structures of power, and “necessity” explores transient spaces of relief and assistance.

At one level, this story can be read cover-to-cover as a continuous, though not necessarily linear–chronological, narrative. Or, a reader may choose to sample different cases – which one might traverse through the book’s cross-referenced structure – to find his or her own way through this contemporary camping life.

“Some camp to escape, while others set up camp to approximate return to a home that is inaccessible or does not exist, still others are forced to camp.”

In the book, I argue that camp spaces are an inexorable environment – one that is unique because it is always being built or rebuilt, always becoming. With this in mind, I began my research trying to understand the localized processes of camping. I really enjoy camping, whether in the backyard or on an abandoned beach. Personal experience is an inextricable and important part of the story of camps; but rituals, communities, and memories of camping practice supersede nostalgia and personal narrative. Camping is place-making.

In the 1990s I went to work for Jersey Devil, a unique group whose members actively participate in building what they design. They also engage this design-build model more deeply by living on the construction site – a practice that broadened my own lived experience of camp and led to a realization that camp is work. More precisely, it is a unique combination of living and working. We site, clear, make, and then break our camps – we accept these often difficult tasks, having been displaced from our normal routine. I investigated this process of camping as place-making in my first book titled Campsite: Architectures of Duration and Place. Following this logic, the campsite maintains the practice of everyday life, and ultimately, for some, it is a method for dwelling.

But what about the situations that move between the ordinary and the extraordinary? What about contemporary situations complicated by politics and globalization, by issues of residency and safety? What happens in spaces caught between permanence and impermanence? In Camps I have sought to understand the spaces of camps that might not always be rooted in the particularities of place or in recognizable, or clearly definable, methods of making home or community. In one section titled “RV Club Camp,” I examine what it means when the U.S. Census designates as “homeless” a burgeoning population of retirees who have chosen to abandon conventionally grounded home-sites for a full-time life on the nation’s roads.

Camps provide clues to how traditional forms of home, lifestyle, tenure, and strategy have been called into question and how they are changing. So, what is a camp? With this query, I overlap Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s important provocation; and while I do briefly cover camp’s biopolitical spaces, I have sought to expand this interrogation to other areas. In doing so, I certainly raise more questions than I answer: What are the origins of response and action? Why are camps chosen? How do camps function?

As interrogatory devices, camps track the exchange of paradox. It has become more difficult to categorically differentiate the temporary from the permanent. Disaster relief camps are often built on contractual impermanence, and languages of control are sometimes applied to sites that originated out of resistance or necessity. In spite of these problems, some camps also suggest alternative ways of working sensitively within sites of paradox and ambiguity.

When I last flipped through Camps, I paused at three moments that give a sense of the range of possibilities, realities, and complexities in the book. Each stopping point includes an illustration that samples the book’s imagery base and that renders “camp space” – one vertical, one horizontal, and the last a shell within a shell not unlike a Russian doll of space, politics, and mobility.

The first, on page 92, is a tree camp. We are looking up through a conifer stand at the undersides of nineteen “tree boats” suspended, and thus truly floating, in a French arboretum’s stately canopy. It’s a children’s camp turned vertical – a site for dreaming and perhaps for redefining self and community. This aerial cluster always reminds me of Italo Calvino’s baron of the trees who silently and symbolically left the dinner table to ascend the canopy permanently and to form an independent state of reflection and play.

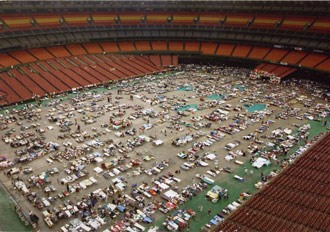

I then turned to page 327 with its birds-eye view of the Benaco camp for refugees in Tanzania. The hazy matrix of tents and shelters extends to the horizon. The Rwandan genocide of 1994 displaced millions, with sites such as Benaco regularly exceeding a quarter-million inhabitants. In this section of the book, I discuss camps that fall between conditions of autonomy and control. For many, Benaco, as well as camps west of Rwanda in Zaire, made visible the scale of such emergencies. It was also an important moment in the process of understanding how interactions of camp, crisis, and need continued to alter forms of assistance and aid agencies.

“Refugee camp” is widely used, but its descriptive breadth hides more particular iterations of dislocation – self-settlement, economic migration, and internal displacement. Kofi Annan called this latter condition – effecting millions of internally displaced persons who reside in “IDP Camps” – the “great tragedy of our time.” These camps are some of the most densely populated places on earth, but the sites are horizontally and marginally distributed where comparable densities are typically vertical and urban, and they are considered temporary when they are essentially semi-permanent. With Benaco camp as a starting point, this section of the book investigates how camps of necessity are planned, protected, named, reported, and inhabited.

On page 424, a photograph, in the news again this summer, triggered my last stopping point. Forty years ago President Nixon greeted the Apollo 11 crew through the sealed rear window of an Airstream trailer serving as a mobile quarantine vehicle. In the next photograph on page 427, the narrative is less visible, but evocatively recognizable nonetheless. In this case, we are looking inside the fuselage of a C-17 military cargo jet between its external hull and the shining metallic shell of an Airstream. Its recreational line once referred to as the “Silver Palace,” this trailer now seals distinguished military personnel from distractions and danger in a military construct known as the “Silver Bullet.” This last example, which I summarize as “In-flight Camp,” demonstrates how camping vehicles and camp spaces sometimes collide and in the process blur distinctions of autonomy and control.

“Camps provide clues to how traditional forms of home, lifestyle, tenure, and strategy have been called into question and how they are changing.”

In the past few months, news and media outlets have reported on homeless camps, at times linking the resurgence of these sites to economic crisis. Last February, the Oprah Winfrey show sent correspondents to Sacramento’s tent cities, which had become global symbols of the recession. In late March, tent cities came up in President Obama’s press conference when a reporter cited a statistic that 1 in 50 children are homeless in the United States.

In some reports, I have sensed a tone of surprise at the degree of self-organization found in many of the tent cities and homeless camps. But instances like the village concept camps in the Pacific Northwest return to essentials of community and demonstrate possible transitional sites – what architect Mark Lakeman has called “dynamic self-help environments.” These spaces are “provisional” in the rooted sense of the word, offering necessary provisions, prospectively looking to the near future, and offering a platform (however transitory) for dignity and humanity.

One main goal of Camps is to provide a preliminary context for critical discussion and for rethinking contemporary issues. I hope to have opened up possibilities for a discipline of “camp studies” – in which camps are not simply vehicles of escape, means to ends, or hasty solutions to problems, but are modes of interrogation themselves. Put another way, camps should not be viewed passively as mere symptoms of the times – Agamben has warned of exceptions becoming the rule – but should be read actively as beacons, warnings, registers, and signals of problem and possibility. Small settlements can rapidly expand in scale and population, the open can just as easily become closed, and eccentric locations afforded by camp’s flexibility offer escape but also result in marginalization and invisibility. Such a discipline must persistently ask “what is a camp?”

Charlie Hailey is Professor of Architecture in the University of Florida’s School of Architecture. A registered architect, Hailey has received numerous awards and grants, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Graham Foundation grant. He is the author of Design/Build with Jersey Devil (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016), Spoil Island: Reading the Makeshift Archipelago (Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space (MIT Press, 2009), also featured on Rorotoko, and Campsite: Architectures of Duration and Place (LSU Press, 2008). His most recent book Slab City: Dispatches from the Last Free Place (MIT Press) with photographer Donovan Wylie was published in October 2018.