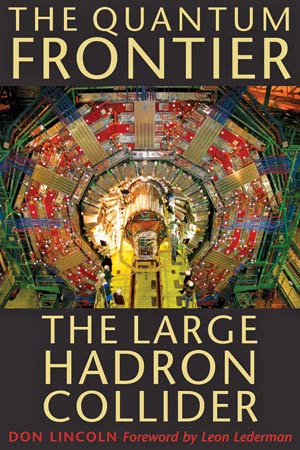

In the fall of 2008, the world’s largest particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider, or LHC, began operations for the first time. Circulating beams of protons under the Swiss and French countryside, the accelerator generated worldwide excitement. A disappointing technical malfunction delayed collisions, but scientists expect to turn the machine back on in October.

It is only a couple of times in a lifetime that a new particle accelerator is launched that can explore an entirely different energy frontier. The Fermilab Tevatron was in 1983 – a quarter century ago. It is expected that the new LHC will dominate the research landscape for the next decade or two.

The Quantum Frontier: The Large Hadron Collider tells the story of this magnificent scientific instrument.

The book’s first chapter is about what we already know, the context for the exciting measurements we expect.

The second chapter reminds that we don’t actually know what the LHC will discover; this is truly terra incognita. However, I do discuss three of the interesting questions the LHC was built to investigate: (1) the elusive Higgs boson, sometimes called the God Particle; (2) supersymmetry, which predicts many new particles and would shed light on a few unanswered questions; and (3) the intriguing possibility that the smallest particles of which we are aware are themselves composed of even smaller particles. (These “smallest” particles are quarks and leptons—current theory treats both as containing nothing within them. The most familiar lepton is the electron; quarks are found inside the familiar proton and neutron.)

The third chapter is about how particle accelerators work and about many of the amazing features of the LHC—including the temperature of the magnets (colder than space itself) and the vacuum in the accelerator (ten times better than the surface of the moon).

Chapter four is about how particle detectors work, and describes the four major detectors arrayed around the LHC’s ring. Two of these detectors include in excess of a hundred million distinct pieces each.

The fifth chapter takes a broader view. Staring deep into the cosmos, astronomers have found that fully 95% of the matter and energy in the universe is of totally unknown kinds. What might the LHC say about these mysteries?

There are other accelerators under consideration and upgrades of older ones. In addition, not all mysteries are found in a particle collider environment. Yet it is deeply intriguing that an accelerator here on Earth can perhaps answer mysteries that span the universe. The Quantum Frontier closes with a discussion of some of the broader issues that contemporary scientists are trying to tackle. It’s a heady time for physics enthusiasts; a paradigm-changing discovery could be just around the corner.

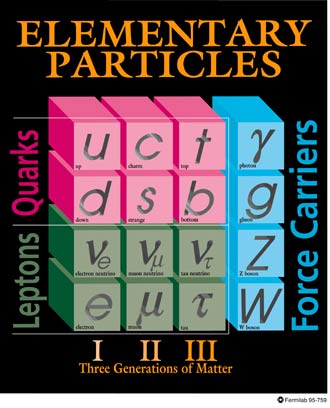

“This impresses the heck out of me… the entire universe is built from very intricate combinations of only three subatomic particles.”

We have come to understand that all the matter we have ever observed is made of a scant hundred chemical elements. The past century has shown that the atomic elements are themselves composed of even smaller objects: protons, neutrons and electrons. It is only in the last 30 years or so that we realized that protons and neutrons are made up of yet even smaller particles still, called quarks. Now we know that the matter of the universe is composed of just three particles: electrons and two different kinds of quarks, called up and down. This impresses the heck out of me… the entire universe is built from very intricate combinations of only three subatomic particles.

Finding the components of matter is only half the story. Something holds things together. There is but one force, gravity, which guides the planets in their stately orbits and also governs the breathtaking precision of an Olympic gymnast doing a vault. Another force, electromagnetism, is responsible for the glory of a brilliant sunset and for what makes impressive the karate expert’s swift strike through a board. Besides gravity and electromagnetism, two other forces have been discovered, simply called the strong and weak force. The strong force holds together the nucleus of atoms, while the weak force is responsible for many types of radioactivity.

That we can use three particles and four forces and, with a suitable instruction booklet, assemble the entire cosmos, is truly a triumph of modern science. But this is not to say that there remain no mysteries. In the course of trying to understand the universe, scientists discovered more particles… ones that seem unnecessary.

For instance, while the electron is a critical component of atoms, in the 1930’s a particle called the muon was discovered. The muon is in many ways just a heavy electron. But the muon is not found in ordinary matter. When confronted with the muon, the eminent physicist I.I. Rabi exclaimed, “Who ordered that?” Indeed, why there should be a “heavy electron” remains a mystery.

And the mystery goes deeper. In the mid 1970’s an even heavier electron-like particle was discovered, called the tau. Just to make things interesting, additional heavy quarks were found. The charm and top quark seem to be essentially heavy up quarks, while the strange and bottom quark seem to be heavy down quarks. Why there appears to be two additional (and heavier, which is probably an important clue) carbon copies of ordinary matter is not known to this day. (An historical tidbit: I was, and still am, a member of one of two teams who discovered the top quark in 1995. We continue to look for a fourth copy, thus far without success.)

When one thinks about the forces, the fact that static electricity and a magnet are really the same thing is not at all obvious. Newton’s realization that the forces that governed the heavens and the fictitious apple that hit him on the head were one and the same remains one of the most important insights of modern science. It only takes a modest amount of imagination to ask “Could the four forces of which we are aware be just different aspects of a single force?”

There are many questions for which one still does not receive a quick answer. Why do some particles have mass, while others don’t? Why are there three carbon copies of matter and not two or four? Or are there four, with the last one waiting for a clever researcher to reveal it? These and countless others might just be answered by the data the experimenters at the LHC will record. This is an exciting time in particle physics research!

While The Quantum Frontier is not a single-topic book, perhaps no question has received as much attention as that of the enigmatic Higgs boson. This undiscovered particle is always mentioned in the thousands of articles describing the LHC that appear in newspapers and popular science magazines. But precisely what this particle is, and why it’s important, is not always talked about. That’s a shame—without this particle or something equivalent, the universe would be a very different place.

The last couple of decades have taught us that the matter of the universe is made of unfamiliar subatomic particles called quarks and leptons. Two kinds of quarks (confusingly called up and down) make up the protons and neutrons of the nucleus of atoms, while the electron is the most familiar lepton. There are two carbon copies of these particles and all of the particles have radically different masses. The very light electron (the lightest of the class of particles that takes its name from leptos, the Greek word for light) has a mass of 0.05% that of a proton, while heaviest of them all, the weighty top quark (a copy of the up quark) has a mass 175 times heavier than the proton. Why should this be?

In the 1960’s, theoretical physicists were able to invent sensible theories that could predict many of the phenomena we observe. However these theories required subatomic particles to be massless—a distinctly not sensible idea. To return sense from nonsense, a proposal was put forth in 1964. Peter Higgs integrated some earlier ideas with his own and suggested that there might be a previously-undetected energy field in the universe which has come to be called the Higgs field.

It is not obvious how the Higgs field can result in a particle, but a water analogy may help. Water is a liquid and fills up all of a container in which it is placed. One might call water “continuous,” as it is not at all trivial to go into a pool and find space “between water.” And yet water is made of molecules consisting of two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms (H 2 O). Water consists of tiny “smallest bits” of water and still looks continuous when viewed at human-size scales.

Similarly, the Higgs energy field consists of countless Higgs bosons. Finding such a boson is a crucial test of Peter Higgs’ idea and it is this search that is the most reported of the many things the LHC scientists are looking for. Reading The Quantum Frontier should give a very good idea of how scientists will know when they’ve found one. (If, indeed, Higgs bosons are there to be found at all.)

“It only takes a modest amount of imagination to ask “Could the four forces of which we are aware be just different aspects of a single force?”

Most books on physics written for the public concentrate on “big ideas” totally forgoing the common question “Yeah, but how do they know that?” That’s where The Quantum Frontier comes in. And while we all must trust experts at some level, it’s comforting to understand why it is that scientists have the confidence that they do. I hope that reading this book will enable a non-scientific reader to understand the principles that govern the LHC accelerator and the detectors that record the data. The experience should be like that of getting a glimpse under the hood of an exotic European race car.

I am sometimes asked why I write books for the public, when the time could be used more profitably to do research. It is a duty, indeed a privilege, to be able to share the excitement of frontier science with the general readers who are interested in the subject. There is another audience I have in mind as well. My path was not an obvious one, for neither my mother nor my father are scientifically-inclined. I am very grateful to my truly-wonderful parents. But they could not provide the kind of scientific role models some of my colleagues enjoyed in their childhoods. To indulge my youthful scientific curiosity I read. Prodigiously. Nothing was exempt, although science fiction was my passion. As I got older, I was introduced to writings by Carl Sagan, and to Isaac Asimov’s popular science books, and to George Gamow. I was hooked… Science fiction is bound only by the writer’s imagination and the reader’s credulity. In science though, there is an answer. It is the universe itself.

Since then, I have devoted my life to the grand study of the cosmos—an endeavor that has spanned human history and will continue long after I have breathed my last. The science that I read now is more technical than what I read decades ago. But the spark started then, with the popular writings of a few who may have known of the impact they would have. Somewhere out there, there are potential young scientists, needing a similar kind of introduction to find their true calling. I write for them.

Don Lincoln is a senior scientist at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory just outside Chicago and an adjunct professor at the University of Notre Dame. He splits his research time exploiting the mature data produced by the DZero experiment at Fermilab and in commissioning the CMS (or Compact Muon Solenoid) experiment at CERN. He is the author of over 300 technical papers, a few popular articles (e.g., in Analog: Science Fiction and Fact), a biweekly column in Fermilab Today, and two books on particle physics for general readers—the one described here and also Understanding the Universe: From Quarks to the Cosmos (World Scientific, 2004). He lives in the Chicago area with his family and a particularly hirsute cat.