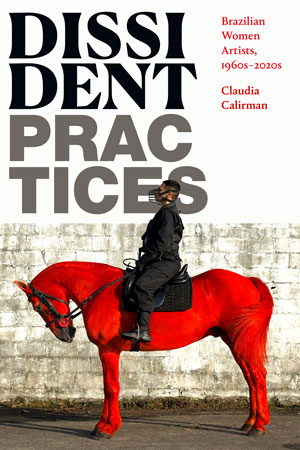

Claudia Calirman Dissident Practices: Brazilian Women Artists, 1960s–2020s Duke University Press 264 pages, 6 x 9 inches ISBN 978 1478016779

In a nutshell

Dissident Practices examines sixty years of visual art by 18 prominent and emerging Brazilian women artists from the 1960s to the present. Through their radical sociopolitical agendas, they affirmed their differences and produced diversity in a society where women remain targets of brutality and discrimination. Dissident Practices spans the years from the military dictatorship in the mid-1960s to the return to democracy in the mid-1980s, the social changes of the 2000s, the rise of the Right in the late 2010s, and the recent development of a more diverse younger generation fighting for gender equality and LGBTQI+ rights.

One of the most intriguing arguments of the book is that many women artists who lived under the Brazilian military regime, which lasted from 1964 until 1985, rejected the term feminism because they viewed it as a North American import. The feminist movement was considered one more hegemonic enterprise orchestrated by the United States. Thus, the choice of these artists not to claim it became part of an anti-imperialist gesture.

There was no Brazilian equivalent to Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, since many female artists had a prominent role in the visual arts in the country. Though they were lauded as key figures in Brazilian art and enjoyed a unique position in terms of visibility, these artists still faced adversity and constraints because of their gender. While many of them disavowed the term ‘feminism,’ they still employed feminist strategies without naming it as such or by finding a better term to define their practices. At the time, political resistance to the dictatorship was the order of the day, and any other issue was considered a distraction; nothing should divide one’s attention. Thus, gender related discussions took a back seat to more pressing matters.

The wide angle

The book is organized thematically in four chapters on different kinds of “dissident practices:” Political Practices, Discursive Practices, Transgressive Practices, and Practices of the Self. The selection of the artists was based on their diverse “practices of resistance,” a term coined by Michel Foucault to convey strategies to build new forms of living and resistance to power. These artists opposed normative policies, resisted authoritarianism, transgressed imposed boundaries, pushed back against female objectification, and challenged construction of “women” as a fixed category. Their works relate to crucial key political moments in Brazil’s history. These include the period of military dictatorship from the mid-60s to the mid-80s, the country’s re-democratization period of the mid to late 80s, its social struggles of the 90s, the ascent of the Worker’s Party in the first years of the 2000s, the return of the Right in Brazil in the mid-2010s, and the emergence of an “overtly feminist art” in the country since 2015. Dissident Practices is not about the history of feminism in Brazil but rather a narrative of a broader history of social resistance from the point of view of women artists.

Dissident Practices builds on my 2012 book Brazilian Art under Dictatorship: Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio, and Cildo Meireles, which analyzes the intersection of the visual arts and politics during the most repressive years of Brazil’s military regime, the so-called anos de chumbo (leaden years) of 1968–75. Growing up in Rio de Janeiro under the military regime and later working as journalist, my inquisitive nature led me to learn more about this repressive period in Brazilian history. More recently, I became interested in exploring a vibrant generation of younger women artists who blossomed in Brazil. at the beginning of the twenty-first century, concomitantly with the “Me Too” movement.

Combining my academic background as an art historian and my professional experience as a journalist, I believe I was in a unique position to analyze the artistic production of this tumultuous six-decade period, from the rise of Brazil’s military dictatorship through the present. Major works by artists such as Anna Maria Maiolino, Lygia Pape, Anna Bella Geiger, Lyz Parayzo, Rosana Paulino, Renata Felinto, Sallisa Rosa, and Berna Reale, among others, are discussed through their anti-authoritarian and transgressive practices.

A close-up

I believe the reader would find interest in browsing Chapter 1, especially the passage on how the Right, the Church, and the Left disdained women’s personal experiences, as they adopted patriarchal views on women’s issues (Pgs. 29-38). The Right was represented by the military dictatorship. The Church embraced old doctrines concerning the family, maternity, and sexuality. The sectarian Left considered men and women genderless soldiers in the fight against the dictatorship. For them, women’s oppression was rooted in class struggle rather than gender or race inequality. This excerpt also explores how the machista attitude of the cultural agents of the time created a dichotomy between feminist and feminine.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, when this study begins, there were fewer opportunities for social mobility in Brazil, and the art scene was restricted to members of the upper and middle classes who had the economic and cultural capital to navigate an elitist art world. Chapter 4 brings to the forefront a younger generation of artists embracing feminism within the context of the 2013 protests that erupted across Brazil. They unearthed the ways in which the fight against gender inequality intersected with newly invigorating resistance to racial and class-based discrimination. Through social media and new forms of self-representation, discussions of gender inequality and debates of race and class discrimination long overdue in Brazilian society come to the forefront, marking major ruptures with past generations. These artists arose from diverse social backgrounds, including Afro-Brazilian, Indigenous, and non-binary groups. They no longer only came from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo—Brazil’s hegemonic cultural centers—but also from various regions of the country outside major urban centers. Through them, a more diverse section of society ascended into the artistic scene. (Pgs. 148-86).

Lastly

The final pages of the book were written during the COVID-19 pandemic. As social distancing became the new norm in 2020-21, bodies were confined to domestic spaces, and social interaction was restricted to technological apparatuses, including Zoom video teleconferencing, social media, email, and the phone. Between friends and colleagues, the exchanges often ended up with the expression “Take care of yourself.” And that is how this narrative came to an end: thinking how these artists took care of themselves during difficult times (not necessarily a global pandemic, but surely during significant periods of struggle). They fought the oppressions of their time, envisioning new ways of living, as they stood up against authoritarianism, patriarchal values, and moral conservatism.

Currently, new dissident practices are already in place, responding to existing and emerging apparatuses of power and tactics of domination, such as biosecurity, cybersurveillance, environmental degradation, sustainability, anthropocentrism, war, and big data. More will come, producing new strategies of emancipation, and promoting varied forms of subjectification. I hope that the story that began here, with its multiple turns, rhythms, and movements, will continuously evolve and adapt accordingly to new challenges and transformations in times to come.