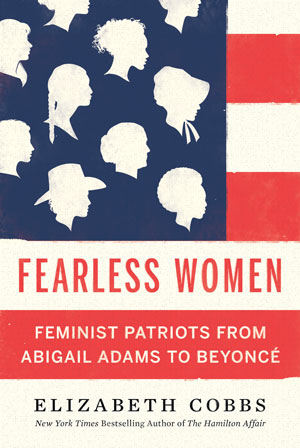

Elizabeth Cobbs Fearless Women: Feminist Patriots from Abigail Adams to Beyoncé Belknap Press 480 pages, 6-1/8 x 9-1/4 inches ISBN 978 0674258488

In a nutshell

What if someone could commit you to an insane asylum for life with a simple signature? Or send your children to live with strangers? Or fire you from your job if you married? Or deposit your paycheck in their own bank account? Or hit you when they felt like it? Or claim ownership over your body and every stitch of clothing on your back, including your underwear?

Today, we take for granted that none of the above is legal. Not long ago, all of it was. Fearless Women shows how each era of United States history made a unique and invaluable contribution to overturning the subjugation of women, step by step. It is the wild, sometimes heart-stopping tale of their fight for simple human rights across eight generations from 1776 to the present.

Even before the Declaration of Independence was signed, Abigail Adams asked her husband John Adams to rewrite everyday laws so that “vicious” men could no longer abuse women “with impunity.” She reminded him, using the Founders’ own language, that “all men would be tyrants if they could.” Please, she asked, “remember the ladies” in the new code of laws. Her husband merely responded, “I cannot but laugh.”

In correspondence with other men, however, John Adams did not find the situation quite so funny. Instead, he soberly warned in 1776 that legislators must be careful not to be too inclusive or, “depend upon it, sir, women will demand a vote.” It took another 144 years, but eventually they got one.

Fearless Women shows that each generation brought something new to the table. One fought for education, another for the right to speak in public. One campaigned for the property rights of married women, another for the marriage rights of single women. Some fought for the vote, others to decriminalize birth control and abortion. At the risk of their lives sometimes, they overturned law after law, custom after custom. The steep climb from there to here was never easy. Looking back, it is inspiring.

The wide angle

As a novelist and historian, I craft stories in intimate ways that allow readers to feel events of the past: from the experience of the enslaved woman who hid in an attic for seven years to save her children, to the Indigenous woman who braved twenty years in prison for killing a child predator, to Susan B. Anthony’s boisterous campaign to stay out of jail for casting a vote. In Fearless Women, each generation is revealed through the biographies of two people: one who worked explicitly for reform and one who barely survived the hazards of her time. Together, each pair helped nail a new rung on the ladder that lifted us to where we are today.

As a Stanford Ph.D., I did not start out as a historian of women, but a scholar of United States foreign relations. Like many people, I considered the fight for legal rights mostly behind us. It was not until I recognized the concerted efforts of traditionalists and authoritarians around the globe to reverse women’s rights that I thought it might be useful to better understand how one innovation built upon the next, and how such efforts facilitated the economic and political development of the United States generally. For example, few historians recognize that female high school teachers laid the basis for industrialization by educating the workforce, or that feminists got the Thirteenth Amendment eliminating slavery on the floor of Congress, or that former suffragists established America’s social safety net.

When we see efforts to ban women from school in Afghanistan, or force them out of public spaces in Iran, or weaken laws against domestic violence in Russia, or limit access to the workplace in China, or criminalize abortion and birth control in the United States, it is useful to understand the historical evolution of such laws and the wide consequences that may result from reversing them.

A close-up

When browsing for a book, I enjoy employing Ford Madox Ford’s “page 99” test. An English literary critic and novelist, Ford wrote in the 1920s, “Open the book to page ninety-nine and the quality of the whole will be revealed to you.” Hypothetically, page 99 should give a reader a window onto the style, purpose, and overall quality of any book.

When I turned to page 99 of Fearless Women after typesetting, I found the story of Elizabeth Packard, a mother of six children who saved herself (along with Mary Todd Lincoln and women in eleven other states) from a lifetime in a frightening, dangerous insane asylum. Page 99 explores the terrible anxiety of Packard’s husband, who worried that she might harm his career as a preacher. Red-haired Theophilus Packard knew that a man who could not control his wife was not considered much of a man by the neighbors, and Elizabeth was just a little too unorthodox in her religious views. Page 99 interweaves the escalating back-and-forth conflict between this husband and wife with information on how the laws of divorce and child custody evolved in the young nation. By the end of the page, Theophilus has begun laying his trap, having decided to lock Elizabeth away where she can do him no harm.

I hope that the Page 99 test shows Fearless Women to be a book that enlightens and entertains while it informs. As a historian, I feel it’s my job to get the dead to stand up and walk. Cry and storm off. Sometimes even to dance and tell jokes. I hope readers will find that I do.

Lastly

I also hope readers will take away a new understanding of the profound impact of the fight for women’s rights on the basic development of the nation. Women’s history is typically treated as a side dish—something readers might be curious about if they have some particular interest in this specialized topic. To give an example of this phenomenon, as of 2023, the Pulitzer Prize in History had been awarded only one time in 107 years to a book on women’s history—and then on the stereotypical subject of midwifery. Yet this blindness literally robs us of half our nation’s story. It is not hard to establish that feminism has been integral to the nation since 1776, if we but look.

I hope readers will also reconsider the term itself, which is often used by both the right and left to divide Americans for partisan purposes. In 1935, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt tried to educate the general public on the subject. She wrote, “The fundamental purpose of feminism is that women should have equal opportunity and equal rights with every other citizen.”

Like other national values, including a free press, fair judiciary, and democracy itself, the importance of feminism must be acknowledged if it is to be defended. This means understanding its historical roots and the immense diversity of its adherents. Susan B. Anthony considered failure impossible if citizens united around the nation’s founding principles. As my last chapter shows, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter shares her faith. Susan B. Anthony might have rubbed her wire-rimmed glasses at the singer’s bespangled shorts in “Run the World (Girls),” but she would have applauded her fellow feminist’s sentiment.