Niko Kolodny The Pecking Order: Social Hierarchy as a Philosophical Problem Harvard University Press 496 pages, 6 1/8 x 9 1/4 inches ISBN 978 0674248151

In a nutshell

Much in our interior mental lives and in our exterior social structures presupposes that we, human beings, are conscious of social hierarchy, of differences in rank and status. This book, first, offers a philosophical analysis of what social hierarchy is. Second, it suggests that we cannot make sense of many familiar ideas about society and politics, both in high theory and in ordinary discourse, without presupposing that there is a distinctive objection to being set beneath another in a social hierarchy—without presupposing that there is a value of “noninferiority.” It is not enough to appeal to the fair distribution of goods and the protection of natural rights, as many political philosophers do.

What are these familiar ideas, which can only be fully explained by an objection to social hierarchy? They include:

- that there is a problem with the state’s “coercion” of those subject to it that requires the state to clear a special bar of “justification” or “legitimacy”;

- that there is a prohibition on “illiberal” interference, such as fines, in choices of certain kinds, such as religion;

- that public officials should not abuse their offices corruptly;

- that people are entitled to democratic structures of decision-making, which give each person, at some appropriate level, if not at all levels, an equal say;

- that there is an objection to discrimination on the basis, say, of gender or race;

- and that people have claims to enjoy the same liberty, opportunity, and treatment that others in one’s society enjoy.

As to how I would like a reader to read the book, it will help, first, to highlight its recurring, three-part structure. It begins with a familiar idea, like one of those listed above. It then observes, negatively, that the idea cannot be explained by appealing to the fair distribution of goods or the protection of natural rights. It then conjectures, positively, that the idea can be explained by appealing to the value of noninferiority, to an objection to being set beneath another in a social hierarchy. It then repeats with another familiar idea, and so on.

Now, it is a very long book. I don’t advise a forward march through the whole thing at first—unless you have angelic patience or a thing for endurance events! The introduction suggests a first pass through the book, which gives the reader one instance of the three-part structure, along with a characterization of the value of noninferiority. With that in the rearview mirror, the reader can then make pit-stops at the topics that most interest them, such as, say, discrimination or democracy.

However, I would hope that if the reader has doubts about the book’s main positive conjecture—namely, that noninferiority is a freestanding value, that there is an objection to social hierarchy that cannot be explained in other terms—that the reader then take the time to read through other instances of the three-part structure before rendering a final verdict. The case for the positive conjecture is ultimately cumulative.

The wide angle

One way to situate the book is simply to see it as contributing to ongoing philosophical debates about particular social phenomena, such as the state, the workplace, discrimination, and corruption. Much of the book is devoted to democracy in particular.

Another way to situate the book is to see it in conversation with other contemporary political theories. As noted earlier, I argue that it is not enough to appeal to the fair distribution of goods, as liberals such as John Rawls do, or the protection of natural rights, as libertarians such as Robert Nozick do. Instead, we need to appeal to a third kind of value. In this, I take inspiration from, on the one hand, the revival of the republican and Kantian traditions, with their focus on domination and dependence, and on the other hand, relational egalitarianism, with its focus on the effects of the distribution of income and wealth on our social relations. I think that the value that animates these theories is what I call noninferiority. However, these other theories either don’t put it in quite the same terms or don’t offer definite articulations of what they have in mind. While I think that we are barking up the same tree, as it were, we have different conceptions of what’s up there.

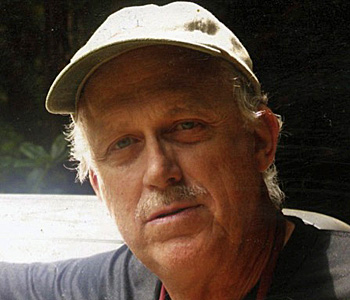

I came to this book from teaching political philosophy to undergraduates at Berkeley. Doing so left me dissatisfied with the existing justifications of democracy. It seemed to me that part of what draws us to democracy is that it does something to put us into relations of equality with our fellow citizens. However, many proposed justifications seemed to look past this simple idea or to characterize it in the wrong terms. The result was then a two-part article on the justification of democracy. After writing it, I then saw, or thought I saw, an instance of a more general pattern. That more general pattern is what the book tries to substantiate.

A close-up

As to what pages of the book I would hope a browser encountered first, I will say, unsurprisingly, the introduction and conclusion. The introduction spells out in a bit more depth the “nutshell” pitch above. It also assures the reader that there is an initial path through the book that requires reading only about a quarter of its total length.

The conclusion presents a different way of thinking about the lesson of the book. That lesson is that what drives much of our political thought and feeling is less, as it may first appear, a jealousy for individual freedom and more an apprehension of interpersonal inequality. The book also might be seen as a kind of slow-motion, anti-libertarian judo. Press hard enough on some complaints of unfreedom and you end up in a posture not so much of defense of personal liberty as opposition to social hierarchy.

Or, perhaps a better way of putting the point is that the opposition to social hierarchy can be understood as a claim to liberty of a different kind. On one understanding of liberty, you are free insofar as you are resourced to chart a life according to your choices. On another understanding, you are free insofar as you are insulated from invasion by others. Noninferiority represents a further conception of liberty: freedom understood as having no other individual as master, as being subordinate to no one.

It is perhaps also worth saying which pages of the book I hope the reader would not encounter first. I wouldn’t want the reader to be plunged headlong into the thicket of detail. By that I mean the stretches in which I argue negatively that we cannot make sense of some familiar idea—such as, say, that the state stands in need of justification—by appealing to a fair distribution of goods or natural rights. Much of the book’s argument is in the weeds, but I don’t expect the reader to descend into them without first getting a reasonably clear view of what’s on the other side of the meadow.

Lastly

The book does not offer policy proposals, or at least specific ones, designed to realize noninferiority. Its aim is rather to understand why values that I take the reader to share are values, why they matter in the first place. For instance, I don’t have any solution to the problems threatening democracy, as concerned as I am, as one citizen among others, about that. But the book does offer one understanding of why the loss of democracy would be a loss.

Perhaps my aspirations for the book are best captured by its closing paragraph:

If we take the longest historical view, the question that we have been exploring comes to seem not a recent, adventitious preoccupation. Instead, it comes to seems one of the first questions of politics: If complex, large-scale society—if, in one sense of the word, civilization—requires a differentiation of roles and a concentration of power and authority, can it be reconciled with the equality of standing that was guarded so jealously before? It is a question that one imagines those on the margins of the first kingdoms and empires must have asked themselves, in that uneasy season between when they first grasped the strange, new terms of life on offer and when they fled beyond the hinterlands or were compelled, by force of arms or lack of alternatives, to accept those terms. The aim of the book has been to suggest that we philosophers bring this question into more explicit reflection.