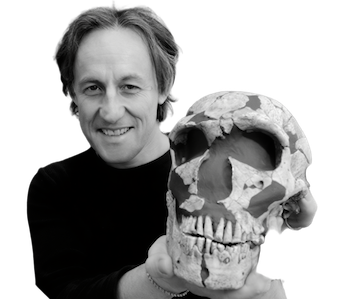

The World Before Us is a story of the human past. If you go back 50,000 years, perhaps slightly earlier, you find this incredible situation on the earth. There weren’t just us, Homo sapiens, there were five, six, seven, maybe even more different species of humans on the planet!The most famous, of course, are the Neanderthals. But in the last two decades archeologists and anthropologists have discovered several more human species that have never been known to science. The Denisovans, who can be thought of as eastern relatives of Neanderthals, the Hobbits on the island of Flores in Indonesia, a species called Homo luzonensis from the Philippines, and Homo naledi from South Africa. It’s also possible that other hominins that we already know existed on earth for a lot longer than we thought and didn’t go extinct until comparatively recently. There is some evidence for that, too. So, my book is essentially a story about humanity, and how we got to this point in our late evolution.Today is very unusual because we’re the only species of Homo on the planet. All of our close relatives have disappeared and gone. Whilst monkeys and apes have lots of living relatives, in the case of us, we’re now alone. If we go back 50,000-60,000 years, however, we see evidence for a big pulse of humans coming out of Africa and expanding outwards into Eurasia, into Southeast Asia, to Australia, to the far reaches of the world, with the exception of the Americas.Around 10,000 years later we also see Neanderthals disappear, and we suspect perhaps Denisovans a little bit later, but we just don’t know because we don’t have very much evidence. But it is accurate to say that, around 50,000 years ago, Neanderthals and these other groups were still around and the world was a much more complex and interesting place. We are not completely sure whether or not these extinctions were our fault. There are a lot of theories and suggestions, some of which I go into in the book, but we know that there was interbreeding between these various groups whenever they happened to meet; the evidence is in ancient genomes extracted from the remains of bones and teeth.