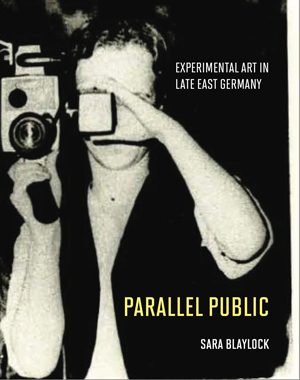

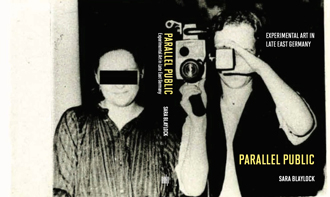

Parallel Public examines experimental art from the final years of East Germany in relation to state power. In the book, I argue that these artists did not practice their art in the shadows, on the margins, hiding away from the eyes of authorities. In fact, many artists cultivated a critical influence over the very bureaucracies meant to keep them in line, undermining state authority through forthright rather than covert projects. In Parallel Public, I describe how the experimental art scene was a form of counter public life that represented an alternative to the crumbling collective underpinnings of the state.The book explores the work of artists who used body-based practices–including performance, film, and photography–to create new vocabularies of representation, sharing their projects through independent networks of dissemination and display. The examples I selected for the book exemplify the material innovation as well as the community-building aspects of the GDR’s small experimental art scene. Gundula Schulze Eldowy’s photographs of exhausted laborers challenged the wooden image of an emancipated proletarian advanced by state culture. The filmmaker Gino Hahnemann who set nudes alight in city parks and imagined a homosocial world for Germany’s cultural heroes fostered a safe creative community for East Berlin’s gay youth. The Leipzig-based independent publication Anschlag collaborated with the exhibition space EIGEN+ART to share the work of experimental artists and writers in public platforms that ultimately reached across the wall to West Germany. In a country that proclaimed but scarcely delivered equality of the sexes, the collective films and fashion shows of Erfurt’s Women Artists Group Exterra XX fused art with feminist political action to compensate for the GDR’s foundational misogyny. Importantly, these creators were as bold in their ventures as they were indifferent to state power. I approach that discussion in a few ways, both of which seek to remedy traditional ways of thinking about life in the Eastern Bloc, which tend to exaggerate state authority over individual life. First, the majority of the examples I explore in the book reveal a clear connection to state apparatuses of culture. The GDR’s experimental artists studied at the country’s art schools; the degrees they received gave them access to membership in the Union of Fine Artists. This means that across their trajectories, from student to professional, artists found ways to use official platforms to publicize or even financially support their efforts. My historicization challenges the traditional dichotomies of official and unofficial art that not only undermine the art of the GDR in broad strokes, but also reinforce narratives of the Cold War that define citizens as either oppressors or oppressed. The image of a victimized citizenry is particularly exaggerated in the mythologies that surround the GDR’s surveillance system, the Stasi. While I demonstrate that the Stasi had an outsized (and largely unanticipated) presence of state security, rather than dwelling on the presumed impacts of the Stasi, I actually demonstrate the agency’s ineffectiveness at curtailing the experimental culture that was its frequent target. The cover of my book reveals this approach most succinctly; I will reflect on the photograph, taken from a Stasi surveillance file, a bit below.In terms of audience, I wrote Parallel Public with an eye toward vivid description, that complements its many reproductions. From original artworks to documentation of events to excerpts from Stasi surveillance files, Parallel Public reveals its archive as much to highlight the subjects I wrote about as to inspire future research or display. I also wrote with a measured and intentional pacing that leads readers from typical impressions of the GDR (oppressed, frustrated) to a more expansive view of the period (collaborative and innovative). The chapters are relatively short and subject heads break the reading in order to accommodate the breaks I personally find necessary when reading.