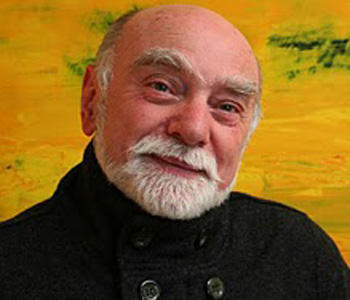

George W. Breslauer

The Rise and Demise of World Communism

Oxford University Press

368 pages, 6 1/8 x 9 1/4 inches

ISBN 9780197579671

The rise and demise of world communism was one of the great dramas of the 20th century. It was born in wars (World War I, World II), and offered an alternative vision of peace and modernity to that of the capitalist world. It was joined together for decades by a common commitment to “anti-imperialist struggle” under Moscow’s leadership. Ultimately, however, most of the sixteen states covered in this book succumbed to the pressures of the Cold War, capitalist globalization, the Sino-Soviet split, and popular disaffection. The result was either systemic collapse (the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe), fundamental economic reforms (China, Vietnam, Laos), or recalcitrant and brittle regimes (North Korea and Cuba). What lessons can be learned from the evolution and fates of communist regimes over the past century?

The book traces communism’s arc: its origins in Marxism and Leninism; its victory in the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917; its construction of an international sub-system (the “world communist movement”); its spread throughout Europe and Asia (plus Cuba); and its ultimate demise, alteration, or stagnation. I focus on the sixteen states that were ruled by single-party, Leninist regimes that were initially committed to comprehensive social, economic, cultural, and political transformation of their societies.

What, then, did communist revolutions and states have in common, in both their domestic and international orientations? How did they differ from each other? What were the appeals of communism that allowed them to come to power? Why did international communism fracture into competing models of domestic and foreign relations? Why did the Soviet Union and, with it, the world communist system ultimately collapse? Is there a future for new communist states?

Informed by both a “comparative politics” and an “international relations” perspective, the book examines the relationships between regimes and their societies, the relationships among communist regimes, and the relations of these regimes with the United States and other capitalist powers. It is the interaction among these three sets of relations that is key to understanding one of the most tumultuous periods, and most powerful ideas, in modern history.

One theme that runs throughout the book is the “drive to difference” among communist regimes after the death of Stalin. The Stalinist template for “building socialism” after the consolidation of power was either imposed or emulated—albeit to varying degrees—by all communist regimes. But after Stalin’s death in 1953, differentiation among communist regimes set in and intensified. These differences appeared in their internal policies, in their societies’ self-assertion, in their relations with each other, and in their relations with the capitalist world. The book categorizes these differing types of post-Stalinist and post-Maoist regimes, with special attention to the difference between “Bureaucratic Leninism” and “Market Leninism.”

In the course of presenting this narrative interpretation of the rise and demise of world communism, I address some of the key questions that animate debate among both advocates and analysts of the communist experience. Would the Bolshevik revolution have occurred had Tsarist Russia not entered World War I? Was Stalinism a logical continuation of Leninism? Was Stalinism a “rational” strategy of “modernization”? What caused the Sino-Soviet split that blew apart the world communist movement? Could US-Soviet détente have succeeded during the Brezhnev era? What explains the Gorbachev phenomenon? How should we evaluate the role of Mao Zedong in the evolution of Chinese communism? (One chapter is titled: “Maoism: An Accounting.”) How did Deng Xiaoping manage to steer China onto a new economic course after the death of Mao? Is China today, under Xi Jinping, heading toward an economic, political, or international crisis? Has the Vietnamese communist party found a formula for combining economic prosperity with political stability? What are the prospects for the North Korean and Cuban regimes, both internally and in their international relations? How should we think about the foreign relations of the five remaining communist states—both with the capitalist world and among themselves?

The final three chapters of the book, respectively, address matters of explanation, evaluation, and prediction. What were the key driving forces that led to differentiation and conflict among communist regimes after Stalin? How might we evaluate the record of communism more generally: as an achievement or a tragedy? And under what circumstances might new ruling regimes appear in the future, run by communist parties and professing commitment to Stalinist or Maoist policies of comprehensive transformation of their societies?

The book provides a synthesis of existing knowledge; it is not based on new primary-source research. It also makes no effort to be comprehensive or encyclopedic. It concentrates on the main themes and arguments. Hence, it does not provide details of leaders’ biographies, particulars of the policy-making process, regional differentiation within communist regimes, or specific features of many of the “satellite” regimes in Eastern Europe and Mongolia. Rather, this is a study of types of communist regimes, their evolution, and their relations with the communist and outside worlds.

In crafting this book, I was inspired by Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, in which very short chapters heightened the drama and kept the reader moving along. My book has 43 chapters in addition to the introduction, and runs 318 pages, plus endnotes. You can do the math. The chapters are short and to the point, yet provide sufficient detail to make the case. As one colleague stated: “I have never seen China’s Cultural Revolution so well depicted in five pages!”

If potential readers came upon this book in a bookstore—and the cover photo is bound to attract their attention—but wanted to get a sense as to what the book is about, they might best read the titles of all 43 chapters in the table of contents. And then, if still interested, they might read pp. 1-8 as orientation to what the book is—and is not. Or, if they want to get a feel for the situation on the ground, they might look at pp. 163-169 on the drama and causes of Sino-Soviet split. There they will see that the issue of nuclear weapons was the trigger for the schism that ensued. In 1957, at a closed meeting of leaders of communist parties from throughout the world, Mao and his associates scorned Khrushchev’s fear of nuclear war, leaving most participants in stunned silence. Indeed, and more broadly, I found that leaders of communist states displayed very different degrees of risk-acceptance in crises that threatened to escalate to the use of nuclear weapons.

How, then, did I come to write this book? I have had a long career as a professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley (since 1971). My first publication was a co-authored book in the field of “comparative communist studies”; it appeared in 1970. Thereafter, I concentrated my research on Soviet and post-Soviet politics and foreign relations. But all along, I kept an eye on what was happening in other communist regimes.

When the field of “comparative communism” hit its stride in the late-1960s, the time that China’s mystifying “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” was ongoing, the concern was principally to understand the difference between Stalinism and post-Stalinism in the USSR and East Europe, the difference between the Soviet and Maoist models of rule, and the ability of “minor” economic reforms in European communism to provide material well-being and political stability. At the time, however, few people could anticipate the dramatic events to come in subsequent decades: rapprochement between the United States and China; Gorbachev’s radical political reforms that unraveled European communism; Deng Xiaoping’s radical economic reforms that unraveled Maoism and led eventually to China’s rise as an economic power; the United States’ military defeat in Vietnam; Vietnam’s and Laos’s emulation of China’s “Market Leninism”; the emergence of a family dynasty in a nuclearized North Korea; or the durability of Castro’s Cuban revolution.

Now that we can look back on both the collapse of European communism and thirty years of the evolution of Asian and Cuban communism, I saw this as a good moment for providing a synthesis that addresses key questions of explanation, evaluation, and—in the cases of the five remaining communist states—speculation as to where they might be headed. Thirty years after the collapse of European communism, much is now clear about the origins and evolution of communist regimes in their many variants. Less clear, of course, is the ultimate fate of those regimes that remain.

I have pitched this book to the educated reader, though specialists on the topic will hopefully recognize the novelty of my interpretations. I have avoided using jargon that might engage specialists in the social sciences while putting off the non-specialist. In all candor, my hope was that professors would assign this book to their undergraduate students in lecture courses on this topic. I pitched the narrative accordingly: insightful and nuanced, but accessible and engaging. I also hoped that the broader, educated public would appreciate an accessible book, of reasonable length, that made sense for them of the nature of communism.

.jpg)

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!