What is your new book all about?

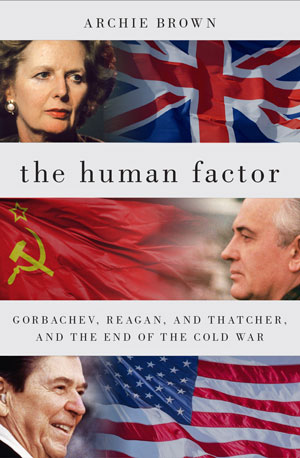

It’s about the biggest political event of the second half of the twentieth century—the end of the Cold War. Linked to that was the transformation of the Soviet system and the de-Communization of Eastern Europe. As the title and subtitle suggest, the book also focuses on three political leaders, their interrelations, and the contribution each of them made to the Cold War’s ending.

The speed and extent of the change took everyone by surprise, but especially those who said that change from within was impossible in the USSR and that no Soviet leader could ever contemplate doing what Mikhail Gorbachev proceeded to do. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher also said and did things in the second half of the 1980s that were unimaginable for their supporters just a few years earlier.

During Reagan’s first term, the Cold War got colder. Who, at that time, would ever have expected to see him standing in front of a large bust of Vladimir Lenin in Moscow State University, telling a Russian student audience in June 1988 that they were “living in one of the most exciting, hopeful times in Soviet history”? And who would have thought that the ‘Iron Lady’, Margaret Thatcher, would become the leading proponent among conservative leaders worldwide of the idea that the political change Communist Party leader Gorbachev was introducing in Moscow was not cosmetic but fundamental?

In 1985, when Gorbachev entered the Kremlin, the Soviet Union was a military superpower. It dominated the Warsaw Pact, the alliance of European Communist states that was the counterpart of NATO. The United States, led by Reagan, was both a military and economic superpower. And though NATO was more of a partnership than was the Soviet-controlled Warsaw Pact, the United States was unquestionably the dominant partner.

Thatcher’s prominent place in the book alongside Gorbachev and Reagan needs, therefore, some explanation. Britain’s superpower days were long behind it, so how does the UK’s first woman prime minister come into the story? An important reason is that she was far and away Ronald Reagan’s favourite foreign leader. They had first met in the mid-1970s, when she was already Leader of the UK Conservative Party but not yet prime minister and Reagan was still several years away from becoming president. From that moment on, he described Thatcher as a “soulmate”.

Her closeness to Reagan in itself made Thatcher significant for Gorbachev, but the warm relationship she established with the Russian politician was not only because of her high standing with the Reagan Administration. She had invited Gorbachev to visit the UK at a time when he was still number two in the Soviet hierarchy, getting to know him three months before he became General Secretary of the Communist Party and thus the Soviet top leader. He spent a week in Britain in December 1984, accompanied, in a break with Soviet tradition, by his wife Raisa. His programme included five hours of discussion with Mrs Thatcher, in which the pair argued vigorously but without rancour. The visit ended with the prime minister famously declaring, “I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together”.

.png)