Henry Jenkins

Comics and Stuff

NYU Press

352 pages, 7 x 10 inches

ISBN 978 1479800933

After decades of disreputable status, contemporary comics are undergoing a transformation into the hard-bound graphic novel, shifting from a disposable to an enduring medium. There has also been a move from the larger-than-life subject matter of superhero comics towards an alternative focus on everyday life. We thus see a shift in what comics depict from urban landscapes and epic battles to still life drawings, which focus the attention on “stuff”—understood as the material objects with which we surround ourselves and the emotional baggage they carry for us, thus becoming our possessions.

Our culture is awash in stuff, and comics are one of the mediums which help us to make sense of our material culture. They do so in three ways: comics are stuff which we collect and appraise; comics depict stuff through their images; and comics tell stories about how stuff enters or exits our life.

Following a two-part introduction which guides readers through key concepts from comics studies, material culture research, art history, and cinema theory, each chapter centers on a contemporary comic artist and their work read through the lens of ‘Stuff Studies.”

So for example, Mimi Pond’s Over Easy, an autobiographical comic about working as a waitress, evokes the tactile dimensions of working in food service; Derf BackDerf’s Trashed shows us the way our trash collectors see our lives through what we discard; and Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits and Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant deal with the emotional and physical labor family members perform in going through what’s left behind after the death of a parent. On the other hand, David Mazzuccheli’s Asterios Polyp captures the ebb and flow in a romantic relationship through a series of panels focused around the furniture arrangements in their apartment, while Emil Ferris’s My Favorite Thing Is Monsters shows a young girl’s transformative practices, such as turning her Barbie doll into a werewolf, because she lacks the resources to collect the paraphernalia associated with the monster culture of the 1960s. Seth and Kim Deitch come at collecting culture from many different perspectives, helping us to think about, in Seth’s case, the ethical relations between rival collectors and in Deitch’s case, the haunted history of popular media. And there’s more.

In each case, our ability to read the social cues associated with the accumulation, display, and discarding of stuff gives us an entry point into the emotional lives of the characters and the particular obsessions of the comics artists themselves. Each, in turn, sheds life on our own everyday practices and our own physical and mental landscape. Comics invite us to read the depicted stuff the ways we might read a friend’s book shelves or knickknack collections.

I wrote this book because on a good day, I see myself as a collector or a pack rat and on a bad day, as a hoarder. I am increasingly overwhelmed by my stuff, possessed by my own possessions. I am sure I am not alone in this ambivalence towards my stuff.

I also find myself drawn to comics that speak to me through my expertise as a collector who is fascinated with “paper” (newspaper clippings, posters, promotional materials, old books), records, toys, monster models, family memorabilia, and so much more. While I have written often about various forms of fan practices through the years, I have avoided until now writing about collecting, per se, because it seemed so directly linked to the commercialization and overconsumption of our current moment. Yet, in this book, I found a way to talk about collecting as a form of grassroots curation, as part of how we construct our identities and make meaning of the world around us.

I was also intrigued by the interdisciplinary shifts in research regarding our relationships to material culture. So far, these new approaches from anthropology, sociology, art history, literary studies, etc., have focused on everyday life or high culture but not so much on popular culture, which has provided both the objects of our collecting and a space where readers, artists, and writers sort through our conflicting feelings in regard to our possessions.

Put these all together, and you get Comics and Stuff.

Although each of the artists I discuss are well known to many comics fans and scholars, many of them have not gathered much critical response so far. Part of my pleasure is opening readers to a wide array of books they might not know about otherwise. Soon, your apartment will be as cluttered with comics as mine is.

Bryan Talbot, from Heart of the Empire

The book has more than a hundred full-color illustrations, many of them full page, each directing attention to the forms of material objects with which comics creators fill their frames and against which they situate their characters. If we assume that a picture is worth a thousand words, this is an author’s dream—another 100,000 words to play around with as I make my argument.

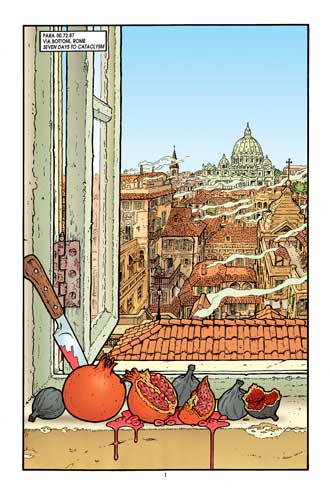

When I flip the pages, my eyes most often end up on p. 73 which features a page from Brian Talbot’s Heart of the Empire: a vivid splash of line and color. Talbot, who knows his art history, draws on several genres of traditional paintings, including both a still life in the foreground and a richly detailed depiction of urban architecture and cityscapes in the background. I love the lush image of the figs and pomegranates both dripping their juices down the windowsill.

Traditional still life paintings often were not entirely still, showing bugs crawling among the flowers, animals romping around the edges, or flowers shedding their petals. Talbot has a particular love for the Edwardian and Victorian era and inserts material objects drawn from references he finds on the web or in his own backyard. Such details represent a form of conspicuous display of his productive capacities, since these images may take days, and he gets paid no more as a commercial artist than if he knocked off a much simpler image.

My other favorite is p. 247, which features an image from C. Tyler’s A Good and Decent Man, which she republished as the omnibus Soldier’s Heart. Here, she provides a detailed depiction of her father’s workroom, including many objects that play central roles across the narrative as a whole and others equally evocative that never surface again in the story. She wants this drawing to capture her father, an embittered World War II vet, in the place he feels most at home and to give that place as much concreteness as she can.

She does something similar with her mother, who is a far less active presence in the book, but whose presence is felt through decorations, especially handicrafts associated with the major American holidays, such as Christmas, Easter, Halloween, and the Fourth of July. Here, the mother is the person who keeps the family going year after year even as Carol, the daughter, is the one who preserves family history.

As the chapter discusses, Soldier’s Heart is structured around a family project as Carol builds a scrapbook to help her father process his repressed wartime memories, while the graphic novel itself functions as a kind of scrapbook as Carol explores how her whole family experienced “collateral damage.” I trace the history of scrapbooking practices and how they have influenced many graphic women as they turn to graphic novels to share aspects of their own lives.

C. Tyler, from Soldier’s Heart

In terms of “comics,” I want to expand the conversation around graphic novels, broadening the range of works that comics scholars discuss, but also changing the ways we write about them. The early emphasis on comics as “sequential arts” has understandably focused a lot of attention on framing, juxtaposition, and decoupage—on how we break down a sequence of images across the page in order to shape the reader’s perceptions. This is perhaps what distinguishes comics from other kinds of graphic storytelling.

I also want to focus attention on mise-en-scène, on the expressive anatomy and material details that are juxtaposed within the same panel, and the invitation comics offer us to scan and flip as we explore their images in search of meaning. Shifting the focus to mise-en-scène offers parallels with a range of other minor arts—such as scrapbooking or cabinets of curiosity or collage—which depend on juxtapositions between elements of material culture.

In terms of “stuff,” I want to encourage reflection on how we narrate our relationships with the things we choose to surround ourselves with. Comics are only one contemporary mode of expression which helps us make sense of our stuff. We might point to the broad array of television programs—such as Tidying Up with Maria Kondo, Hoarders, or Antiques Roadshow—or YouTube’s unboxing videos which address our societal fascination with everyday things.

And I draw analogy to a number of artists and literary figures—Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, Henry Darger’s scavenger art, Jonathan Franzen’s list-making in The Corrections, and Kare Walker’s reclaiming of racist iconography. All of this suggests that the social and cultural questions surrounding collecting, accumulation, inheritance, possession, and culling have implications far beyond the specific comics I discuss here.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!