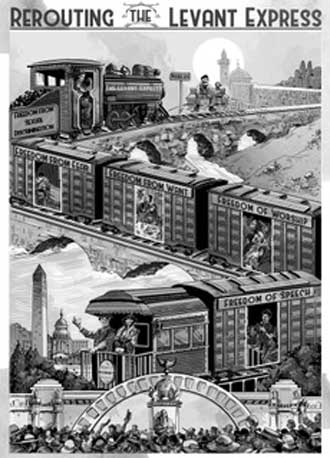

First, the book title, The Levant Express, is a metaphor representing the demands for human rights that raced across the Arab world like a high-speed train during the Arab uprisings of 2011. Within two years, the fast moving revolutionary contagion slowed to a halt. When the Arab Spring turned into the Arab Winter, some governments (Egypt and the Gulf monarchies) reestablished even more repressive authoritarian regimes, while other states (Libya, Syria, Yemen) devolved into civil wars. What led to those uprisings and their tragic consequences? My book addresses those questions by identifying how patterns of revolution and counterrevolution have played out in different societies and historical contexts. I then apply those insights toward offering hopeful and realistic proposals to reroute The Levant Express.What makes my book unique are the arguments I offer for hope, and the paths that I offer for resuming the advance of human rights in the Middle East. Other experts view the region as trapped in an endless maelstrom, or offer incremental steps aimed at one or another immediate crisis. True, the region has been beset by a long history of political repression, economic distress, sectarian conflict, and violence against women. But that history pales in comparison to the tragedies of the West, which was also plagued by religious wars, and by two World Wars that brought Europe unprecedented devastation.Hopefully, readers will be stimulated and informed by the lessons I draw from those European struggles and apply to the Middle East, and by my identification of current possibilities, including subterranean social forces for progress. I remind readers that before the defeat of Nazism, Franklin D. Roosevelt envisioned a post-war reconstruction effort based on foundational principles of freedom. His Four Freedoms (Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear) paved the way for the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Marshall Plan, Bretton Woods, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. History offers no better success story than these post-World War II endeavors. We need to remember that sustainable peace needs to be planned even during times of war.In short, this book is attentive to the current plight of people in the Middle East. It also challenges the pessimistic malaise that undermines Western interest in developing substantive plans for regional progress. It prods readers to resist succumbing to populist, protectionist, and nationalist fervor, and to understand why a restored international liberal order requires a peaceful Middle East. For example, the refugee crisis in Europe cannot be addressed without human rights, political stability, and economic opportunity in the Middle East and North Africa. Our futures are intertwined.