When we think of breaking images, we assume that it happens somewhere else. We also tend to think of iconoclasts as barbaric. Iconoclasts are people like the Taliban, who blew up Buddhist Bamiyan statues in 2001. We tend, that is, to look with horror on iconoclasm.

This book argues instead that iconoclasm is a central strand of Anglo-American modernity.Our horror at the destruction of art derives in part from the fact that we too did, and still do, that.

This is most obviously true of England’s iconoclastic century between 1538 and 1643. That century of legislated early modern image breaking, exceptional in Europe for its jurisdictional extension and duration, stands at the core of this book. That’s when written texts, especially poems, rather than visual images, became our living monuments.

Surely, though, the story of image breaking stops in the eighteenth century, with its enlightened cultivation of the visual arts and the art market. Not so, argues Under the Hammer: once started, iconoclasm is difficult to stop. It ripples through cultures, into the psyche, and it ripples through history.

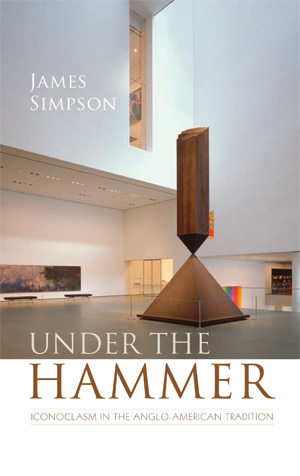

Museums may have protected images from the iconoclast’s hammer, but they also treat images as dangerous. Aesthetics may have drawn a protective circle around the image, but as it did so, it also neutralised the image.

The ripple effect also continued across the Atlantic, into puritan culture, into twentieth-century American Abstract Expressionism, and into the puritan temple of modern art.

Mid-twentieth-century abstract painting is, in fact, where this book starts: the image has survived, just, but it bears the scars of a 500 year history.