The Embattled Vote explains why Americans have fought and died for the right to vote. The book is more relevant than ever after the Supreme Court sanctioned partisan gerrymandering in a ruling issued on June 27, 2019.The world’s oldest continuously operating democracy guarantees the franchise to no one, not even citizens. This lack of universal voting rights originated in a crucial mistake by America’s founders: omitting a right to vote from the Constitution and leaving the franchise to the discretion of individual states. During Reconstruction, Congress missed an opportunity to rectify the founder’s error and enshrine a positive right to vote in the Constitution. Instead, they framed the Fifteenth Amendment on racial voting rights negatively, in terms of what states could not do. They set a precedent for later amendments on sex and age.

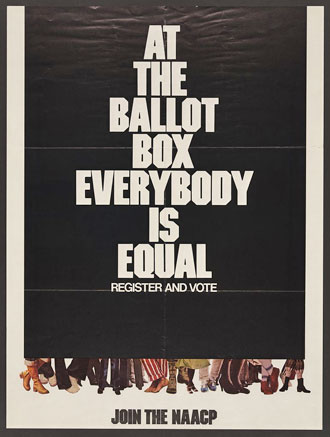

The lack of a constitutional guarantee has meant that the right to vote has both expanded and contracted over time. In the early republic, only those with a “stake in society” proven through the ownership of property or the payment of taxes could vote in most states. In the nineteenth century, states eliminated economic qualifications but embraced the ideal of a “white man’s republic,” with people of color and women excluded from the franchise.Despite advances since adoption of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, our voting rights are still in jeopardy. Politicians that benefit from voter suppression rely on bogus claims of voter fraud to deprive millions of American of the franchise through voter identification laws, political and racial gerrymandering, registration requirements, felon disenfranchisement, and voter purges.In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down one of the Act’s most effective provisions, which required states and localities with a history of voter discrimination to preclear changes in voting laws and procedures with the U.S. Justice Department or the Federal District Court in D.C. The Court held that the “pervasive,” “flagrant,” “widespread,” and “rampant” discrimination that Congress sought to correct in 1965 no longer existed in the 21st century.

Yet, by neglecting new forms of voter suppression, the Court unleashed a renewed push to erode voting rights. Dallas minister Peter Johnson, a civil rights activist since the 1960s, said, “There’s nobody that’s going to shoot at you if you register to vote today. They aren’t going to bomb your church. They aren’t going to get you fired from your job. You don’t have those kinds of overt, mean-spirited behaviors today that we experienced years ago ... They pat you on the back, but there’s a knife in that pat.”Historically, players in the struggle for the vote have changed over time, but the arguments remain depressing familiar and the stakes are very much the same: Who has the right to vote in America and who benefits from exclusion?