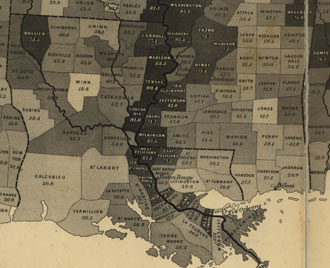

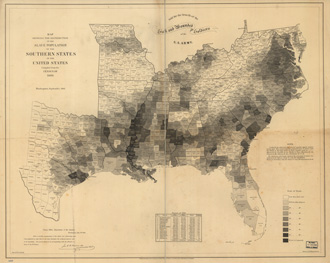

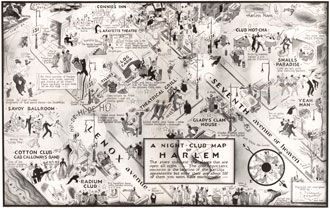

From the voyages of discovery to the digital age, maps have been essential to five hundred years of American history. Whether made as weapons of war or instruments of reform, as guides to settlement or tools of political strategy, maps invest information with meaning by translating it into visual form. Maps captured what people knew, but also what they thought they knew, what they hoped for, and what they feared. As a result, maps remain rich yet largely untapped sources of history. This premise animates A History of America in 100 Maps.Organized into nine chronological chapters, the book examines both large-scale shifts but also little-known stories through maps that range from the iconic to the unfamiliar. Readers will encounter maps of political conflict and exploration, but also those whom we rarely consider mapmakers, such as soldiers on the front, Native American tribal leaders, and the first generation of young girls to be formally educated.The book can be read as a continuous narrative, though readers may page through the book to discover a particular image that captures their imagination. Some will be drawn to the map used by the British Crown to negotiate the boundaries of the new United States at the end of the Revolutionary War. Others will be riveted by a map drawn to study—and stem—the rampant gang behavior in Chicago during the 1920s. Each map is accompanied by a brief essay that lays out its context, establishes its significance, and connects it to the larger story. Through these maps, we gain a greater appreciation for the contingencies of the past, but also the degree to which maps were integrated into all aspects of American life.The book is now in its third printing. What has most surprised me about this success is the wide and diverse audience it has reached—a direct function of the many strange and appealing images that I was able to share.