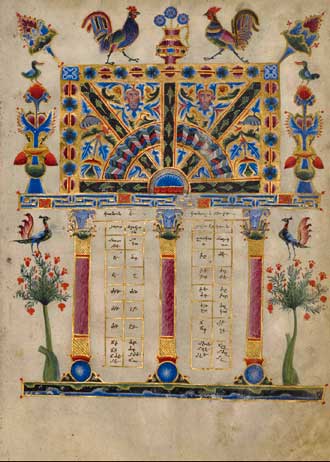

In 2010, the world’s wealthiest art institution, the J. Paul Getty Museum, found itself confronted by a century-old genocide. The Armenian Church in Los Angeles was suing for the return of eight pages from the Zeytun Gospels, a manuscript illuminated by the greatest medieval Armenian artist, Toros Roslin. Protected for centuries in a remote church, the holy manuscript had followed the waves of displaced people killed during the Armenian genocide. Passed from hand to hand, caught in the confusion and brutality of the First World War, it was cleaved in two. Decades later, the manuscript found its way to the Republic of Armenia, while its missing eight pages came to the Getty in California.

The Missing Pages is the biography of the Zeytun Gospels, a medieval manuscript that is at once art, sacred object, and cultural heritage. The book follows in the manuscript’s footsteps through seven centuries, from medieval Armenia to the killing fields of 1915 Anatolia, the refugee camps of Aleppo, Ellis Island, and Soviet Armenia, and ultimately to a Los Angeles courtroom. The story of how the pages came to be missing unfolds the entire tragic history of the Armenian people in the 20th century.

The tale of this beautiful and meaningful object and its extraordinary journey embody some of the defining elements of art history in the 21st century. I take the much-publicized legal battle as a point of entry to explore how contests over art objects are framed, what cultural heritage signifies to survivor communities, and how institutions like museums curate and display works of art with painful histories.

Reconstructing the path of the pages, I sought to uncover not only the rich tapestry of an extraordinary artwork, but also the individuals and communities touched by it. At once a story of genocide and survival, of unimaginable loss and resilience, The Missing Pages captures the human costs of war and persuasively makes the case for a human right to art.