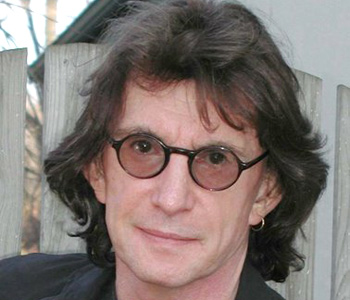

Alastair Bonnett

Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

Chicago University Press

304 pages, 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches

ISBN 978 0226513843

In Beyond the Map I explore our curious but intense relationship to place by telling the story of thirty-nine extraordinary places. It’s a geographical roller coaster. But it’s not just a thrill ride. Beyond the Map takes us to new islands that are rising in the Arctic; a ‘Garbage City’ in Cairo; a guerrilla garden in England; and remnants of a utopian undersea village. Each of the thirty-nine chapters offers a unique and surprising story and, I hope, pushes us to think about why place matters, and why we still pour our hope and dreams into it.

It is often said that the planet is becoming ever more the same: that unique places are disappearing and that there is nowhere new left to explore. Beyond the Map turns all that on its head and shows that the world is riddled with strange, hidden places; some are remote and exotic, but others are just around the corner or under our feet.

There is a new mood in the air: a rising rebellion against blandness and sameness, and it has been a long time coming. You don’t have to walk far into our coagulated roadscape to realise that, over the past hundred years or so, we have been much better at destroying places than creating them. I see that every day in my home city, Newcastle, in England’s far north, which has been pulled apart and rebuilt so many times that its now hard to recognise. The resulting landscape feels impermanent; temporarily bolted into view. To illustrate that point, one of the chapters takes us to the bizarre and dilapidated ‘skywalks’ that some hare-brained local planner carelessly strung across Newcastle city centre in the 1970s. So many of us have to pick our way through something similar; the soon-to-be-debris; broken layers of other people’s grand and not so grand plans.

So that’s Beyond the Map. It is a travel book with a difference. It takes us to deeply unusual destinations – it even includes a chapter on a noisy traffic island – in order to think about what place means to us.

In the early 1990s I got involved with one of the more outré forms of geography, known as psychogeography. This involved a lot of unplanned, drifting walks and purposely getting lost by using a map of one place to navigate oneself around another. We thought we were terribly avant-garde but, in hindsight, what strikes me about the yearning that spurred us to re-enchant the ordinary world, is just how ordinary and widely shared it is.

If I’m honest, my need to find places that are, often literally, ‘off the map’, is not an intellectual or political project but something felt. I blame Epping. It’s where I was born and grew up. It’s one of many commuter towns near London, pleasant enough but, with each passing year, becoming that bit less distinct; merging into an ever-widening penumbra of other suburban nowheres. As I used to rattle out to Epping on the subway or drive there along London’s orbital motorway, I often felt as if I were travelling from nowhere to nowhere. In response, escaped territories, enclaves of otherness, shy hints of the past, leftovers and remnants, took on a totemic power.

Eventually I became a professor of geography; though it is those early memories that still remind me that geography is not a dead list of facts but something urgent and emotionally charged. I have another important memory. Visiting my granny as a small boy, in her chilly house surrounded by overgrown fields, I’d wrinkle my nose at the thick scent of coal tar soap, mothballs and door blankets; hear the ticking clock above the snapping coals in the fire. I was swaddled in the past. We’d drive to her remote Suffolk village across sandy heaths and pass row upon row of neat new terraced homes behind the high wire fences of the adjacent US Air Force base. The serried lines of back garden barbecues, as well as the base’s substantial pile of ‘free-fall nuclear bombs,’ all seemed primed and ready to go. The contrast between the fuggy comfort of granny’s home and the prospect of Armageddon, of the winding down, the falling away of village life and the spectacle of world-shaping power, lodged itself in my heart. I began to understand that places are strange, layered, full of ghosts and possibilities and that they have stories to tell.

Beyond the Map is the kind of book you can dip into anywhere. Reviewers often call it ‘quirky’ and the individual chapters are very different from each other; some are sombre (for example, the chapter on the geography of the Islamic State) but many are playful (for example, the chapter where I tell the story of how my street declared independence from Britain after the UK’s ‘Brexit’ vote).

Playful or not, every chapter investigates our changing and curious relationship with place. A good example is my attempt to find a legendary ‘phantom tunnel’ in the busiest train station in the world. About four million people a day pass through the countless levels, 200 exits and 36 platforms of Shinjuku Station in the heart of Tokyo. It is a temple of efficiency and signage, but there is a legend attached to it. It’s not a legend from days of yore; it’s a modern legend that reflects the fears and fantasies that come to life in an overwhelming metropolis.

Sometimes called the Bermuda Triangle of Tokyo, the story goes that some commuters never make it home. They take a wrong turn, then another, get flustered, run down the wrong stairs and end up in the wrong elevator, until they find themselves quite alone in a quiet corridor, the soft boom of a distant underground train sounding somewhere far above them. They are never seen again.

On a hot and humid day in late August I entered Shinjuku’s maw. It’s not rush hour, but people are pouring through the broad, immaculately clean and well-signed corridors. I thought I’d need to get through the ticket barriers to go into the belly of this thing, but after some toing and froing through a few of them, with the assistance of some puzzled staff (the barriers here open to let you in, but if you haven’t gone anywhere they won’t let you out), I’m finding that the loneliest spots are in the meeting ground between the station and the giant shopping complex that engulfs it. For all its many exits and corridors, the station is just one element of a much bigger labyrinth. It is in this interzone where the crowds thin out and I am able to worm my way down deeper and deeper, heading into the furthest and quietest corners of the labyrinth. It takes about twenty minutes, down an escalator, down some more stairs and another escalator, before I’m anywhere that isn’t a major thoroughfare. It’s a stairwell with no signage and I head down again; and here the noises of the crowd have softened to almost nothing. It’s a beguiling contrast; the idea of ever returning up there, I suddenly realise, is deeply unappealing. It’s so nice to hear the clip of my own footsteps. The lighting here is not so bright, the cleaning regime less evident; there are even a few items of litter, blown down from above, and a man is slumped against a huge paper shopping bag on the flight below me. He’s very still, his unseeing eyes focused on nothing ...

There is a growing feeling that the replacement of unique and distinct places by generic blandscapes is severing us from something important. If only in a small way, I hope Beyond the Map contributes to this pushback. Both this book and its prequel, Unruly Places, have been widely translated, finding readers in Korea and China, as well as in Germany and Spain. As the tide of globalization and urban change sweeps the planet so too does a fascination with unique, intriguing, storied places. They have become redoubts of the imagination. We need these places, and the sooner planners, developers, authorities of all sorts, get that and stop shredding our landscapes and our memories, the better.

Another task I want to aid in Beyond the Map is the reinvention of exploration. Exploration is a rather tarnished concept because it conjures images of colonialism and one group of people pushing another out of the picture. But the desire to explore cannot be defined around one historical event or period. It is an innate human attribute and one of our species’ most glorious qualities. For me, exploration today means understanding that, despite the best efforts of Google Earth, our world is still full of the unexpected and uncharted. Such regions may be beneath the waves or nearby; they may require long, difficult journeys or we may walk straight past them every day. The distance traveled is irrelevant: real exploration does not test our wallets or our shoe leather but our imagination.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!