A Future in Ruins tells the story of UNESCO and its efforts to save the cultural wonders of the world, largely through its famous World Heritage program. I wanted to understand how and why the past comes to matter in the present, who shapes the political agendas, and who wins or loses as a consequence. Today it remains critical that we educate ourselves about the politics at work in cultural productions such as World Heritage and understand that we can never escape the past and are, in fact, too often doomed to repeat it.

Forged in the twilight of empire and led by the victors of the war and major colonizing powers, UNESCO’s founders sought to expand their influence through the last gasps of the civilizing mission. Beginning as a program of reconstruction for a war-ravaged Europe, UNESCO soon set its sights on the developing world. Its aim was to formulate and disseminate global standards for education, science, and cultural activities. However, it would remain a one-way flow, later to prove problematic, from the West to the rest. Within a matter of years, the philosophical appeal for cultural understanding and uplift, a culture of peace no less, would be sidelined by the functionalist objectives of short-term technical assistance.

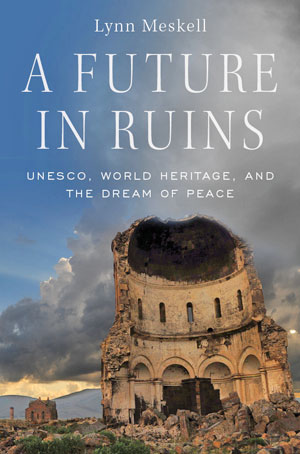

Ruins were also on the agenda for reconstruction.

But it was not simply that great buildings, museums, and art were affected by the war and required rehabilitation. It was the regulation of the past itself, and how it might be recovered, that was deemed part of a new world order. How archaeological excavations were conducted around the world and the resulting discoveries were disseminated also required restructuring. Ultimately, archaeology’s spoils were to be divided up for Western advantage, echoing earlier recommendations made by the League of Nations.

The past would be managed for the future. UNESCO capitalized upon an already existing momentum for a world-making project devoted to humanity’s heritage. What followed was an inevitable progression from the vast conservation and restoration efforts needed in the wake of destruction after two world wars toward a more lasting project of rehabilitation and recovery.