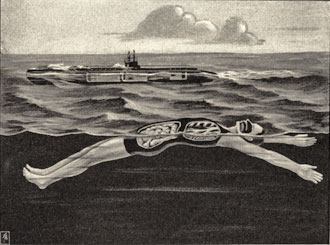

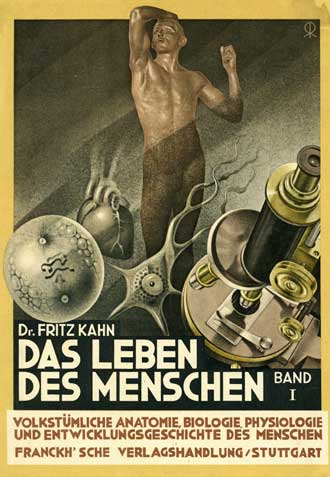

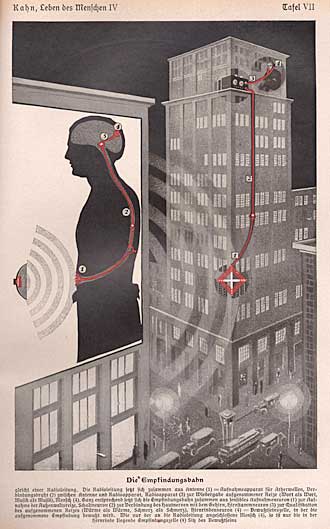

Body Modern focuses on the history of a peculiar kind of imagery of the human body: the conceptual scientific illustration. Primarily found in America and Germany between 1915 and 1960, images of the body modern also traveled to the Soviet Union, China, Latin America, and many other countries, as well as across time; the book follows them to the twenty-first century, where they regularly appear in videos, training manuals, websites, textbooks and magazines—our media environment and experience.To clarify: Body Modern is not about pictures that teach lessons about the anatomical structures of the body, but about pictures that attempt to entertain and instruct readers with visual explanations of the workings of the human body, using metaphors, sequences, analogies, diagrammatic elements, cross-sections, allusions, playful situations, and juxtapositions. To us, such images seem familiar, something that has always been around, but the genre was novel and remarkable when it was invented in Chicago in the first decades of the 20th century.Its first great exponent was Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), a German-Jewish physician and popular science writer. In collaboration with a cadre of commercial artists, Kahn brilliantly deployed and redeployed––he was a great recycler and repurposer of his own pictures as well as those of his predecessors and contemporaries––thousands of illustrations, in books, articles and posters that reached a mass audience in Weimar Germany and around the world.Body Modern bombards the reader with images from the works of Kahn because Kahn’s pictures were one very remarkable, but now mostly forgotten, part of a pictorial/media regime change, a cultural revolution that aimed to remake the relationship between text, image, and body, and remake, perhaps re-engineer, human subjectivity.