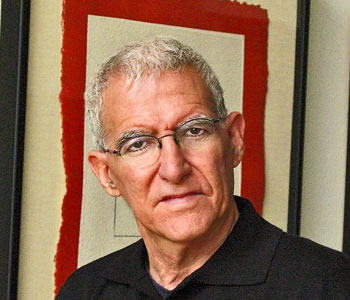

Teofilo F. Ruiz received his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1974. He has published or has forthcoming fourteen books and more than seventy articles. He has received numerous awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, the Mellon and Guggenheim Foundations. In 1994-95, he was selected as one of the Outstanding teachers in the United States by the Carnegie Foundation, and as the Distinguished Teacher at UCLA in 2009-10. One of his books, Crisis and Continuity, was selected for the Premio del Rey Award by the American Historical Association. Ruiz is presently a Distinguished Professor of History and of Spanish and Portuguese at UCLA.

This book is, first and foremost, a reflection on the human condition and on the manner in which we attempt to explain the world and make meaning of our lives. It is, most of all, about the manner in which humans, either collectively or individually, attempt to deal with catastrophes, with the injustices that are part of history, and with the inexorable passing of time.While grounded in my wish to answer the concerns and existential questions that students have posed to me throughout my almost forty years of teaching, I also wish to address these questions for myself.I have long grappled with these issues. I do not know that I have provided an answer either to the reader or to myself, but I have tried as honestly as I can to deal with these topics.What I do, therefore, is to try to show how in the western world humans have sought to make meaning of the world in which they live, and to explain to themselves and others the reasons for the brutal exercise of power, natural disasters, and acts of inhumanity against other people. I look over the long expanse of western history as a broad canvas in which to place these discussions, drawing examples from different periods in history.Although there are many different ways of coping with the “terrors of history,” I focus on three specific answers to the question of how we deal with the passing of time, historical disasters, and natural catastrophes.These three ways are a) religion; b) embracing the material world or sensual experiences; and c) the desire to understand and explain the crimes of history and the cruelty of nature through aesthetics, that is, to render the world and all its problems into art.In dealing with religion, I seek to show how religion provides solace to many individuals in spite of the incomprehensible nature of some of history’s great crimes. Religion, in orthodox and heterodox variants, seeks in the end to abolish history and to stop time. I explore examples—often taken from literary and historical sources—of the embracing of sensual pleasures as a means to combat the horror of existence. Finally, I look at art as a way in which the same results are achieved.I do not argue that one path is preferable or superior to the other. Often they overlap. But I also argue that these three ways of making meaning in the world are forms of escape from history and time. A parallel argument is a polemics against the idea of progress. If, on the one hand, by progress we mean technological advances, an increase in our material culture, and other types of economic and technological developments, then one must agree that there is progress. If, on the other hand, we wish to measure progress in terms of men and women’s humanity and kindness to other humans, then the last century and the last decade are vivid examples of the kind of crimes that individuals and nations perpetrate against other people in the name of religion, patriotism, and greed. That is certainly not progress.

Teofilo F. Ruiz The Terror of History: On the Uncertainties of Life in Western Civilization Princeton University Press200 pages, 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches ISBN 978 0691124131

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!