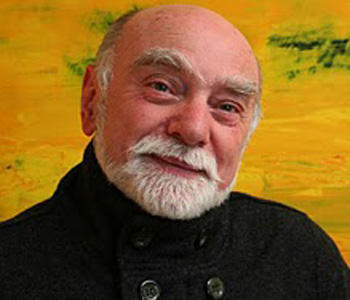

Alex Rosenberg

The Atheist's Guide to Reality: Enjoying Life without Illusions

W. W. Norton

368 pages, 5 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches

ISBN 978 0393080230

Most people think of atheism as one big negative. But there is much more to atheism than knockdown arguments that there is no God.

There is the whole rest of the worldview that comes along with atheism. It’s a demanding, rigorous, breathtaking grip on reality, one that has been vindicated beyond reasonable doubt. It’s called science.

The scientific worldview requires atheism. It can’t be an accident that 95 percent of the members of the US National Academy of Science (along with their foreign associate members) don’t believe in God.

But science also enables atheists to answer all of life’s universal and relentless questions. Some of the answers it provides are disconcerting. Several are surprising. But they are all as certain as the science on which our atheism is grounded.

So why aren’t scientists more up-front about these answers that we can read right off of science? Mainly because the answers are bad PR for science in a nation of churchgoers.

If science made you an atheist, you are ready for serious scientific answers to the rest of life’s persistent questions.

Here is a list of most of these questions and their short answers. Given what we know, they are all pretty obvious. The interesting thing is to recognize how totally unavoidable these answers really are. The book explains them in more detail.

Is there a God?

No.

What is the nature of reality?

What physics says it is.

What is the purpose of the universe?

There is none.

What is the meaning of life?

Ditto.

Why am I here?

Just dumb luck.

Does prayer work?

Of course not.

Is there a soul? Is it immortal?

Are you kidding?

Is there free will?

Not a chance!

What happens when we die?

Everything pretty much goes on as before, except us.

What is the difference between right and wrong, good and bad?

There is no moral difference between them.

Why should I be moral?

Because it makes you feel better than being immoral.

Is abortion, euthanasia, suicide, paying taxes, foreign aid, or anything else you don’t like forbidden, permissible, or sometimes obligatory?

Anything goes.

What is love, and how can I find it?

Love is the solution to a strategic interaction problem. Don’t look for it; it will find you when you need it.

Does history have any meaning or purpose?

It’s full of sound and fury, but signifies nothing.

Does the human past have any lessons for our future?

Fewer and fewer, if it ever had any to begin with.

The Atheist’s Guide to Reality is a tour through the science—mainly physics, evolutionary biology, and cognitive neuroscience—that shows why these short answers to the persistent questions are the right answers.

It doesn’t matter what part of The Atheist’s Guide I may want people to open up first, it’s a safe bet browsers will go right to chapters 5 and 6: “Morality: The Bad News” and “The Good News: Nice Nihilism.” It’s the persistent questions about morality that grip most people, not the trivial topics of the first 4 chapters, like the nature of reality, the purpose of the universe, or the inevitability of natural selection.

After all, the trouble most people have with atheism is that if they really thought there were no God, human life would lose its value. They wouldn’t have much reason to go on living, and even less reason to be decent people. The questions theists always ask atheists are these two: In a world you think is devoid of purpose, why do you bother getting up in the morning? And in such a world, what stops you from cutting all the moral corners you can?

Religious people especially argue that atheists cannot really have any values—things we stand up for just because they are right—and that we are not to be trusted to be good when we can get away with something. They complain that our worldview has no moral compass. These charges get redoubled once theists see how big a role Darwinian natural selection plays in science’s view of reality. Many of the most vocal people who have taken sides against this scientific theory have frankly done so because they think it’s morally dangerous, not because it lacks evidence. If Darwinism is true, then anything goes! “Anything goes” is nihilism, and nihilism has a bad name.

As the chapters about ethics suggest, there is good news and bad news. The bad news first: We need to face the fact that nihilism is true: science can’t justify the core morality that almost all of us accept. And any other supposed justification would conflict with science. So, if we are going to be really consistent, nihilism is the only option.

But the good news is that evolution made most of us nice, cooperative, even altruistic people. The moral monsters that we run into are as few and far between as saints and Samaritans. This is just what you would expect of any very complex trait subject to natural selection: most people are distributed in a bell shaped curve around a pretty high average level of niceness. But there is no way to prevent the occurrence of outliers at the extremes. We just need to guard ourselves against the psychopaths (and maybe protect the saints against being exploited).

These two chapters,that I predict people will want to read first, show that the same factors that made almost all of us nice also make for nihilism about morality. I hope and I also believe that nice nihilism is enough to forestall atheists’ worries. Because when it comes to morality, it’s all we’ve got.

The Atheist’s Guide to Reality is not a how-to or self-improvement book. There are already far too many books tempting gullible people who think that all they need to change their lives is a convincing narrative. But there is a lot of science we can take to heart and make use of, bending our lives in the direction of less unhappiness, disappointment, and frustration, if not more of their opposites.

Neuroscience shows that reading this book will rearrange a large number of neural circuits in your brain (though only a very small proportion of the millions of such circuits in your brain). If those rearranged neural circuits change your answers to the daunting questions, then this book will have worked. You will find yourself enjoying life with fewer illusions.

Which ones? Here are a couple:

Don’t take narratives too seriously. When politicians or political commentators try to sell you on a narrative become suspicious. Things are always more complicated than any story we can remember for very long, even if the story happens to be true. Being able to tell a story that voters can remember is almost never a good qualification for elective office.

This advice goes double for anyone trying to sell you on religion or stories of self-improvement. Religion and those who make their living from it succeed mainly because we look for stories with plots everywhere. We need continually to fight the temptation to think that we can learn much of anything from someone else’s story of how they beat an addiction, kept to a diet, improved their marriage, raised their kids, saved for their retirement, or made a fortune flipping real estate.

Once you adopt science, you’ll also be able to cease treating the humanities as knowledge. Disputes about the meaning of works of art, literature, and music, are ones in which all disputants are wrong, since they are arguing about whose illusion is correct.

What about our own emotional lives? If you enjoy being unhappy, if you really get off on the authenticity of the tragic view of life, science has nothing much to say. You are at the extreme end of a distribution of blind variations in traits that Mother Nature makes possible and exploits. To condemn these extreme traits as wrong, false, incorrect, bad, or evil is flatly inconsistent with nihilism.

On the other hand, if you are within a couple of standard deviations of the mean, you will seek to avoid, minimize, or reduce unhappiness, pain, discomfort, and distress in all its forms. If so, science has good news. There is an ever-increasing pharmacopeia of drugs, medicines, treatments, prosthetic devices, and regimes that will avoid, minimize, or reduce these unwanted conditions. But you can write off any treatment whose provider excuses it from double-blind controlled experiments on the grounds that you have to believe in it for the treatment to work. Even placebos pass the double-blind test.

Science has nothing against having a good time. In fact, it observes that we were selected for seeking fun. It serves our genetic interests most of the time. Not all the time, of course. But by now our brains have become powerful enough to see through the stratagems of Mother Nature. We can get off the Darwinian train and stop acting in our genes’ interests when they conflict with having fun. There can’t be anything morally wrong with that (recall nice nihilism) if that’s what we want to do.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!