Carolyn Bronstein

Battling Pornography: The American Feminist Anti-Pornography Movement, 1976-1986

Cambridge University Press

280 pages, 6 x 9 inches

ISBN 978 1 107 40039 9

Battling Pornography chronicles the formation and development of an American feminist anti-pornography movement from 1976 to 1986. The book emphasizes the internal movement dynamics and external structural factors that supported a progression from a campaign against images of sexual violence in mainstream media, especially advertising, to a focus on pornography, including nonviolent, sexually explicit expression.

The majority of what has been written about the anti-pornography movement concentrates on the mid-1980s efforts of the legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon and the radical feminist author Andrea Dworkin to introduce anti-pornography ordinances that classified pornography as a legally actionable form of sex discrimination.

My book has a different emphasis. I focus on the pre-MacKinnon and Dworkin years, tracing the emergence and development of the three most influential feminist media reform groups that led the movement in the 1970s and early 1980s: Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW), Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media (WAVPM), and Women Against Pornography (WAP). This history sheds new light onto the gradual evolution of a full-fledged feminist anti-pornography movement.

In restoring the history of these groups, I intended to locate the origins of anti-pornography activity in grassroots campaigns against sexually violent and sexist mainstream media content. For example, WAVAW led a national boycott of the record companies owned by Warner Communications from 1976-1979 to protest the use of images of violence against women on album covers and in related promotional material.

They objected to albums like Love Gun, by the rock band Kiss, whose title fused sex and violence. The album cover showed dozens of women fawning at the band members’ feet. This kind of message, they argued, imposed corrupt and artificial gender roles on both sexes, teaching women to be passive and subordinate and men to be brutish and controlling.

These feminist groups tried to disrupt and subsequently improve mainstream media images. They shared a goal of ending rape, battering, sexual harassment and other forms of sexual violence. Using national consumer action and public education techniques, as well as conferences, marches, and demonstrations, these organizations led a creative and innovative battle to improve the media, reduce violence against women, and create optimal conditions for true sexual liberation.

But, at the same time that advertising and other mainstream media captured activists’ attention, the question of pornography always hung in the air. Over time, movement leaders began emphasizing pornography—downplaying the broader issue of sexualized media violence—because they believed that this strategic rhetorical shift would bring media attention and public support.

The book captures the gradual transformation of the anti-media violence campaign into an anti-pornography movement, complete with rising tensions over the potential for censorship and threats to sexual freedom and speech rights.

I show that anti-pornography was a complex and multifaceted movement made up of diverse and overlapping feminist groups who articulated different opinions on pornography. Feminists who opposed violence did not uniformly oppose pornography, and they did not simply fall in line behind MacKinnon and Dworkin as the movement progressed.

In Battling Pornography, I locate the roots of anti-pornography sentiment in a series of interrelated social and political conditions that shaped women’s lives during the late 1960s and early 1970s. As a media scholar, I wanted to make sense of the factors that motivated women to identify sexually violent media as a major cause of female oppression. I sought environmental triggers.

My answer to that question rests on women’s shared interpretations of several significant social phenomena.

First, I link the movement to the failed promise of the sexual revolution to provide true liberation for women. The sexual revolution did enlarge women’s right to engage more freely in sexual behavior, but it provided little support for women to define their sexuality free of male standards and expectations. This led to feelings of exploitation; women were angry about a revolution that privileged male desire and access.

Next, I examined related ideological changes in the Women’s Liberation movement in the years prior to the rise of anti-pornography organizations. Within the consciousness raising groups popularized by radical feminists, women opened up to one another about experiences of male sexual violence, especially rape and battering. New knowledge about the prevalence of these acts exacerbated women’s anger at the oppressive aspects of sexuality. They began to view sexual violence—including mediated depictions—as part of the system of power that men had created to ensure female subordination.

Radical feminism also inspired women to evaluate the institution of heterosexuality critically. Radical feminist theory held that the everyday structures of heterosexuality, such as the family, were organized in ways that encouraged male supremacy. Mass market pornography in this period was predicated on heterosexual male enjoyment, a reality that led women to regard the proliferation of pornography in the 1970s with suspicion and anger.

Once pornography moved into the mainstream of American life, as evidenced in the early 1970s by the unprecedented success of Deep Throat, thriving adult magazines like Playboy, Hustler, and Penthouse, and liberalized U.S. obscenity laws, the stage was set for the rise of a feminist protest movement.

Some readers will be familiar with the better-known aspects of the feminist anti-pornography movement, particularly efforts led by Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon in the mid-1980s to pass new legislation. This duo sought to introduce ordinances, first in Minneapolis and then in Indianapolis, that defined pornography as a violation of women’s civil rights and made it actionable under the law.

Fewer readers, however, will know about the earliest years of movement activity, especially the efforts of grassroots groups like Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW) to combat violent and sexist media content, especially advertising.

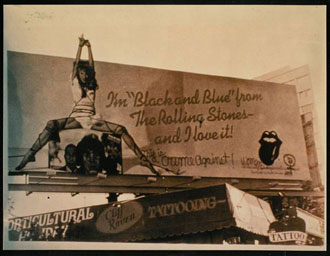

If a prospective reader were to pick up Battling Pornography in a bookstore, I hope that the book would fall open to page 93. This is where I begin to tell the story of feminists’ encounter with the 1976 advertising campaign for the Rolling Stones’ album, Black and Blue. The campaign centerpiece was a billboard that featured a bound and bruised woman.

At 14 by 48 feet, high above Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, the billboard dominated the skyline. The woman wore a lacy white bodice, artfully ripped to display her breasts. Her hands were tied with ropes, immobilized above her head, and her bruised legs were spread apart. She straddled an image of the Stones, with her pubic bone positioned just above Mick Jagger’s head. Her head was thrown back, eyes closed, and her mouth hung open in an expression of pure sexual arousal, as if the rough treatment had wakened her desire and now she wanted more. The ad copy celebrated the mythic connection between sex and violence, reinforcing the dangerous idea that women get excited when things get a little rough: “I’m Black and Blue from the Rolling Stones and I Love It!”

To anyone familiar with the music of the Stones, this blatant sexism was not surprising. On tour in 1975, Jagger rode a twenty-foot-long inflatable stage prop shaped like a penis while singing Starfucker, a song about the pleasure he derived from sex with girl groupies. (Note to Maroon 5’s Adam Levine: Try that move like Jagger.) Karen Durbin, editor-in-chief of the Village Voice in the mid-1970s, went on the road with the band and found herself isolated and “engulfed by an all-male world” where women were regarded primarily as eye candy and one-night stands.

The Los Angeles-area feminists who formed WAVAW were outraged by the Black and Blue promotion. They thought that the campaign made light of male violence, especially battering. They feared that linking such violence with a chic rock-and-roll band like the Rolling Stones gave battering a stamp of social approval. In a news release, the activists explained how the billboard made women feel. “We carry in ourselves a deep fear of rape. When we would drive down the Sunset Strip and see the myth about our lust for sexual abuse advertised, our fear and outrage was deepened,” the group warned. “We are not Black and Blue and we do not love it when we are.”

Anyone who opens to page 93 and keeps reading will find out how this story turns out. I can promise that the efforts of WAVAW to call attention to sexist violence in media will surprise you—and quite likely inspire you.

Photo courtesy of Northeastern University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

Where are we on the pornography question? Should Americans reopen a national conversation about the proper place of pornography in our society, and how we think such material might affect human sexuality?

Will the creation of the new .xxx adult content internet domain (which is designed to bar images of child pornography and make it easier for people who seek sexually explicit material to find it and keep those who do not at a comfortable distance) do enough to reduce the feeling that we are wallowing in an endless sea of mechanistic, silicone-enhanced images?

The vast dissemination of pornography through the internet is said to be liberating for sexual minorities who might otherwise have trouble finding one another as well as erotic materials that feature their preferred practices. But, for many others, the prevalence of pornography contributes to a gloomy and dehumanized view of sexuality.

In Battling Pornography, I trace the efforts of American women in the 1970s and 1980s to call national attention to the dangers of media images that conflated violence and sexuality. Over time, they shifted their attention to pornography and argued that the constant depiction of women as sexual objects robbed them of their humanity and denied them full civil rights. The conflicts and debates among feminists in this period, who were split between anti-porn and pro-sex positions, as well as between feminists and civil libertarians, were intensely personal and bitter.

In the 1980s, the feminist effort to do something concrete about the pornography problem brought up widespread fears of government censorship and restrictions on sexual freedom. Opponents of anti-pornography feminism argued that labeling a certain class of sexual images as exploitative endorsed a conservative sexual worldview that privileged some forms of sex, especially heterosexual and procreative, over others. Since that time, many social critics have been loathe to raise the pornography question, rightly fearing that its mere mention brings the taint of these charges.

A hope that I have with regard to Battling Pornography is the possibility of reinvigorating these debates without raising the specter of censorship or sexual conservatism.

We have not solved the initial problem that feminists identified regarding sexually violent media depictions, and the role that media play in teaching young women and men about their sexuality and gender norms. And, pornography in the internet age is a reality of social life—not one that can or should be eradicated, certainly, but one that can be discussed rationally.

The book offers a critical evaluation of the feminist pornography debates and shows how the turn toward legal solutions distracted attention from the core questions—still relevant today—about media effects and gender. Perhaps reading it will help steer those debates back on track and allow us to reconsider the fundamental question of whether pornography disseminates at least some messages that are harmful for both women and men.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!