Mark Lynn Anderson

Twilight of the Idols: Hollywood and the Human Sciences in 1920s America

University of California Press

238 pages, 6 x 9 inches

ISBN 978 0520237117

ISBN 978 0520267084

Twilight of the Idols is ultimately a book about the central importance of deviance to the formation of American mass culture during the 1920s.

Given our current media obsessions with unusual crimes, bizarre occurrences, and public scandals, such an assertion is perhaps not all that surprising. Yet, what has changed with our contemporary media, and what has been one of its most determining characteristics for the last ninety years, is the ability to maintain a strong distinction between representations of deviance as news and information (crime reportage, political scandal, biographies of the famous and the infamous) and representations of deviance as entertainment (fictional movies, video games, popular music).

Of course, some media forms exist at the boundaries of such a distinction—reality television, for instance, or the celebrity tabloids. Yet, these are the exceptions that prove the rule.

Consider, for example, how often we pursue the tabloids in the supermarket line as a temporary amusement. Part of the fun of tabloids comes from their sheer outrageousness, from their unconvincing masquerade as serious news. Significantly, this fun also rests upon the joke that is on some imagined audience who might, in fact, take the tabloids seriously, an audience who might just mistake these sensational stories for real news.

In other words, we assist the dominant media in upholding the distinction between social discourse and entertainment by continually postulating a pathological audience incapable of adequate cultural discrimination. A portion of our pleasure in the consumption of deviance comes from the very properness of our appreciation of those media forms that deliver it to us. Appreciating the difference between news and amusement is an important means of being normal in our society today.

Twilight of the Idols is about a moment just prior to this particular epistemological separation of consumers of mass culture from the worlds that are depicted there. This separation had to be achieved, in part, so as to maintain a set of divisions upon which modern social authority rests—divisions between public and private, work and leisure, self and other.

Twilight of the Idols looks at the historical possibilities that early Hollywood celebrity culture posed for overcoming such divisions, as well as the way those possibilities, those dynamic new ways of experiencing and knowing the world, were attenuated by evolving film industrial practices, by the multiple regulatory responses to the many star scandals that filled the nation’s headlines from 1921 to 1926, and by the consolidation of the human sciences of psychology, sociology, sexology, and ethnography.

While liberal left critics in America today typically view celebrity culture as a burdensome popular distraction taking citizens away from the real political issues facing our world, I have written an elegy for a lost moment when mass cultural reception, particularly the reception of Hollywood stars, was a principal site of social involvement.

While liberal left critics in America today typically view celebrity culture as a burdensome popular distraction taking citizens away from the real political issues facing our world, I have written an elegy for a lost moment when mass cultural reception, particularly the reception of Hollywood stars, was a principal site of social involvement.

The book’s larger project is to describe the importance of the Hollywood cinema in founding those disciplinary practices that helped institutionalize contemporary scientific approaches to the study of the individual person.

Such a project is, of course, indebted to Michel Foucault’s work on the history of disciplinary power. But I seek to account for the richly uneven and contested nature of the deployment of those discourses through which individuals were surveyed, measured, named, classified, and studied by the modern sciences as deviants, delinquents, criminals, and perverts.

Before being relegated to the status of objects for the new sciences, Hollywood and it audiences helped produce the very forms of knowledge about the deviant individual that now constitute so many forms of professional expertise. In their stories and in their themes, the popular motion pictures of the 1920s reflected, not surprisingly, the emergence of the “new psychology” and other up-to-date thinking about human behavior. More importantly, the cinema itself also became the terrain upon which the critical question of personality was most fully elaborated and through which new understandings of contemporary identity were forged.

One of the social projects to which the American cinema and the human sciences contributed during the 1920s was the promotion of a new appreciation of each individual as now subject to the terms of a particular narration: the life story of the person as case study.

Early scientific case studies in criminology, in sociology, in psychoanalysis, or in cultural anthropology, sought to demonstrate, through a sustained accounting of an individual’s life, the operation of complex social and environmental factors. Different from traditional biography or hagiography, the case study told of an individual who was no one in particular—except to the extent that he or she led an exemplary life of crime or, perhaps, pursued the gratification of an unusual perversion.

My interest in the prevalence of the scientific case study in the early twentieth century is intimately related to my interest in the early Hollywood star system, whose almost simultaneous emergence I perceive as another significant iteration of a prevailing case-study episteme.

A portion of the research I present in Twilight of the Idols has to do with attempts by the motion picture industry to contain star scandals by explaining how particular stars had become deviant or diseased.

A common explanation for the perceived excesses of star behaviors in the early 1920s was that the industry had developed too rapidly, leaving some individuals ill-prepared for the sudden wealth of stardom. According to this perspective, the escalating success of the film industry produced unforeseen conditions for a small amount of its workers, allowing them to pursue self-destructive life-styles.

While Hollywood wished to portray the scandals as a temporary aberration of rational business expansion, the public and the press took a far more sustained interest in the lives of troubled stars as a way of understanding how modern society works.

We get glimpses of this possibility today when a major star scandal occurs. But the potential for a popular scientific engagement with scandal is always quickly contained by media strategies that were innovated in the 1920s, now aided by an American left, whose unthinking critique of the culture industry continues to make vast sectors of people’s everyday lives virtually meaningless, or at least unusable for political engagement or expression.

One of those strategies is the “privatization” of the star’s life, the enforced partitioning of the known details of a particular scandal from having any lasting or meaningful relevance for the public beyond a questionable entertainment function. Such a partitioning is maintained by both the media industry and those cultural critics who diminish the importance of celebrity scandals by self-righteously pledging their respect for privacy while they accuse the media of pandering to prurient interests in the name of profits and ideological diversion.

The first chapter of Twilight of the Idols is a sustained analysis of the privatization of matinée idol Wallace Reid’s heroine addiction during 1922 and 1923.

But the industrial containment strategy devised back then can still be seen at work today. For example, just prior to his death from a fatal combination of sleeping pills and painkillers in early 2008, Heath Ledger’s complaints about fatigue and insomnia suggested that his production schedules were a determining factor in his passing away at twenty-eight years of age. However, the controversy quickly turned to an investigation of the physicians who had prescribed the medications, and it more or less ended with Ledger’s former girlfriend Michelle Williams mystifying the star’s death by explaining how the actor’s difficulties with sleep were the result of “an underlying sensitivity” that was unknown to the public.

In other words, an understanding of drug abuse as tied to a contemporary mode of living was transformed into an inscrutable, idiosyncratic characteristic of the actor himself; the objects of a popular social investigation have here been reduced to celebrity trivia.

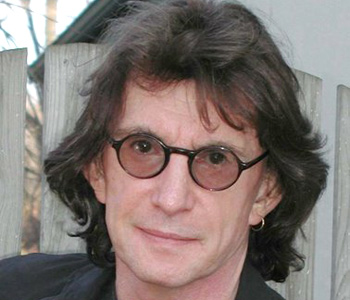

A new mode of stardom. Nathan Leopold, Richard Loeb, and their chief defense attorney, Clarence Darrow, in 1924. Chicago Daily News press photograph courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.

For me, the key chapter of Twilight is the short chapter on Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb.

Many people today have only the vaguest notion of the these two young men who, in the summer of 1924, were sentenced to life plus ninety-nine years for the kidnapping and murder of a fourteen-year-old boy who lived in their wealthy Chicago neighborhood.

Three motion pictures have recounted their case from varying perspectives: Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion (1959) and Tom Kalin’s Swoon (1992).

But the newspaper coverage of the trial of Leopold and Loeb was a self-reflexive demonstration of how the new media situation created by Hollywood’s celebrity culture might involve a mass audience in a process of producing the very terms by which health and disease were to be understood in the modern era.

Because Leopold and Loeb pled guilty and avoided a jury trial, their team of lawyers were allowed to provide evidence that these two young men, while unusually gifted with intelligence and social charms, had committed this crime out of a compulsion that could only be comprehended by considering the myriad circumstances of their respective lives and their unique relationship.

Thus the trial was devoted to hearing testimony from psychologists and alienist who detailed the two young men’s biographies, their fantasies, and their worldviews. Because of the sustained and extensive attention given to the details of their private lives, Leopold and Loeb quickly achieved the status of celebrities. While the defendants never took the stand, they were constantly interviewed by the press during the trial and were photographed in and out of the courtroom, usually depicted as deeply interested in themselves, their trial, and the public that paid attention to them.

In many ways, Leopold and Loeb were continually shown to be consuming themselves as media images, with Loeb “confessing” at one point that he didn’t mind spending the rest of his life in prison if he could only have a scrapbook containing all the newspaper accounts of his trial. This media coverage brought people together, but not as a sham jury waiting to mete out some form of populist justice through public opinion. Instead, the publicity generated by the trial allowed a mass public to take an active interest in the psychological and social processes of personality formation while simultaneously understanding and expressing their own relations to deviance.

The possibilities implied by the non-directed reception of the star criminals in 1924 had to be contained by closely regulating the representation of the trial’s audiences, making either incoherent or pathological any appeal the killers might have held for the public.

In other words, public opinion had to be constructed. Yet, even today, the smallest details of the case are capable of producing a powerful fascination, though now such fascination is usually followed by a sense of corrective guilt, a guilt that continually seeks to become collective.

We assist the dominant media in upholding the distinction between social discourse and entertainment by continually postulating a pathological audience incapable of adequate cultural discrimination. Appreciating the difference between news and amusement is an important means of being normal in our society today.

I wrote Twilight out of a love for late silent cinema, but the book has little to do with cinephilia or with the films themselves.

I am more concerned with the sort of audiences that the Hollywood films of the era imply and, more broadly, with the sort of society that made the late silent cinema in America possible.

While I hope that my book might add in some small way to the growing number of works that take seriously the interrelations between culture and the history of science, my greater wish is that Twilight makes it more difficult for media scholars to assume the innocence or simplicity of earlier audiences of the mass media.

Schooled in post-structuralism and postmodernism, we like to pride ourselves on having sophisticated notions about identity. We find it fairly unimaginable that large sectors of the public prior to, say, the Second World War were capable of conceiving of identity as relational, of having a nuanced understanding of the unconscious, or of thinking race, gender, and sexuality to be amenable to personal, social, and historical transformations. To the extent that such sophistication is cherished by us as properly the domain of social scientists, media experts, and cultural critics, I want readers of Twilight of the Idols to question at what cost such professionalization was won and at what costs it continues to be maintained.

Yet, and this is perhaps my own delusion, I wrote this book out of respect for and in solidarity with the perverts of the past.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!