Stuart Banner

American Property: A History of How, Why, and What We Own

Harvard University Press

340 pages, 6 1/8 x 9 inches

ISBN 978 0674058057 hb

ISBN 978 0674060821 pb

When Richard Newman died in Los Angeles in 1997, his body was taken to the county coroner’s office for a routine autopsy. Two years later, Newman’s father learned that the coroner had removed his son’s corneas for transplant without asking the family’s permission. He sued the coroner’s office for damages, on the theory that the office had violated the Newmans’ constitutional rights by depriving them of property without due process of law.

But were Richard Newman’s corneas a kind of property? And if they were, who was their owner once he was dead?

This case, like many others, raises a basic question: what is property?

To decide whether a dead man’s corneas are property, one has to develop some idea of what property means and some method of distinguishing what should count as property from what should not. To do that, in turn, requires some thought about the nature of property itself. How does it originate? What purposes does it serve? What are its outer limits?

American Property is about the ways in which the answers to questions like these have changed over time.

One approach to understanding these changes is to look closely at the emergence of new forms of property in response to technological and cultural change. Several of the book’s chapters are about such episodes: they examine, for instance, the development of property in news in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the emergence of property in sound in the early twentieth century.

Another approach is to look at changing ideas about the limits of appropriate government regulation of property. Some of the chapters examine the rise of new kinds of regulation and the development of new ideas about the Constitution’s protection of property rights.

The basic message of the book is that our ideas about property have always been contested and have always been in flux. Property is a human institution that exists to serve a broad set of purposes. These purposes have changed over time, and as they have, so too has the conventional wisdom about what property is really like.

Lawyers of the eighteenth century could not have known of the array of intangible property rights the future would bring. But they were not in the grip of any physical conception of property, because they were familiar with a different set of intangible property rights.

Property is both a technical legal subject and an important part of everyday life. So I have tried to write an account that does justice to both without losing either specialists or general readers.

The book avoids getting bogged down in the technical detail that so often dominates discussions of the history of property, especially those written by lawyers. But I have explain that detail when it is important to understand the big picture.

The history of property has not received as much attention as it deserves. I think that’s because historians have been put off by what seems to be legal complexity, while lawyers tend to be interested in the past primarily as a repository of facts useful in making normative arguments.

As a result, much of what we think we know about the history of property turns out not to be true.

For example, the conventional story about the development of property is one of a long run transition from tangible to intangible forms of property.

The idea is that the important kinds of property two or three hundred years ago were physical things like land and livestock, while the important kinds today are non-physical things like patents and copyrights, shares of corporations, and so on. And, furthermore, that this transition from the tangible to the intangible required people to start thinking very differently about property.

I show in the book that there were plenty of non-physical forms of property in the past. Some of those no longer exist—property in public office, and property in the labor of others.

Lawyers of the eighteenth century could not have known of the array of intangible property rights the future would bring. But they were not in the grip of any physical conception of property, because they were familiar with a different set of intangible property rights.

The real transition would not be from physical to non-physical property, but rather from one group of non-physical property rights to another.

Another example involves the conception of property as a “bundle of rights.”

Lawyers usually think of property as a collection of rights to do various things—the right to possess, the right to use, the right to exclude, the right to transfer, and so on. This idea of property is conventionally traced to the progressives of the early twentieth century, and is understood as a conception that facilitated the greater regulation of property, and the correspondingly reduced constitutional protection for property, characteristic of that period.

In the book I show that the idea of property as a bundle of rights is actually much older. When it first became widely held, it had a political significance exactly the opposite of the one ascribed to it in the conventional story.

Property was first understood as a bundle of rights in the nineteenth century in order to argue for greater constitutional protection for property rights, and thus less regulation.

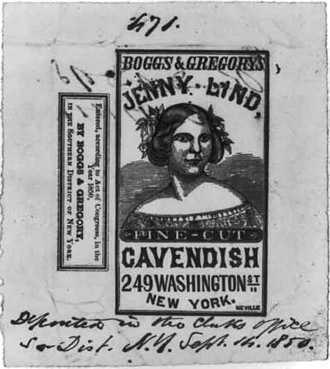

A label for Jenny Lind tobacco, just one of the many unauthorized products bearing her name that Lind encountered on her 1850-52 tour of the United States. (LC-USZ62-86770, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.)

Chapter 7, “Owning Fame,” is about the rise of property rights in the names and images of famous people. I bookend the chapter with the stories of two celebrities, Jenny Lind and Elvis Presley.

Lind was the blockbuster performer of the mid-nineteenth century. Her 1850-1852 tour of the United States packed concert halls from New York to New Orleans and back again.

Lind’s promoter was P.T. Barnum, no stranger to innovative ways of making money. Everywhere the tour went, shopkeepers were selling Jenny Lind merchandise. “We had Jenny Lind gloves,” Barnum recalled, “Jenny Lind bonnets, Jenny Lind riding hats, Jenny Lind shawls, mantillas, robes, chairs, sofas, pianos.” There were Jenny Lind stoves and even Jenny Lind chewing tobacco and cigars, despite Lind’s aversion to cigars.

Yet none of these products earned Lind or Barnum a cent. Lind’s celebrity was obviously a valuable asset—but neither Lind nor Barnum conceived that Lind had any right to prevent others from commercially exploiting her name or image.

None of the manufacturers or sellers of Jenny Lind merchandise thought he needed Lind’s permission. Indeed, Barnum was happy so many people were slapping Lind’s name on their products, because it was proof of her popularity, which promised that the concerts would sell out. It apparently never occurred to him that they were taking money out of Lind’s pocket.

A hundred years later, a new kind of property had come into existence. When Elvis Presley toured the country in the 1950s, he likely earned more from licensing fees than from ticket sales. There were Elvis shoes, Elvis jeans, Elvis record players, Elvis bracelets, Elvis lipstick, Elvis statues in plaster of Paris, and much more.

By 1956, still very early in Elvis Presley’s career, thirty companies had fifty licenses for Elvis products to be sold in the country’s leading department stores. Presley’s licensing agent was Henry G. Saperstein of Beverly Hills, whose other clients included Lassie and the Lone Ranger.

Back in the 1850s, P.T. Barnum had been pleased to discover unauthorized Jenny Lind merchandise. In the 1950s Saperstein sometimes discovered unauthorized Elvis gear, and when he did, “we sue like mad,” he explained. “We’ve never lost a case yet. The courts protect you all the way.”

Back in the 1850s, P.T. Barnum had been pleased to discover unauthorized Jenny Lind merchandise. In the 1950s Saperstein sometimes discovered unauthorized Elvis gear, and when he did, 'we sue like mad,' he explained.

Philosophers and law professors sometimes try to discern property’s “true” nature. But the stories in this book suggest that property is not something that has a true nature.

What one thinks property is depends on what one wants property to do—that is, what goals one is trying to advance by thinking of property in a particular way.

Property is not an end in itself but rather a means to many other ends. Because we have never had unanimity on how to prioritize those other ends, we have never had unanimity on an understanding of property.

In the course of this push and pull, advocates on all sides have made, and still make, claims about property—about its origins, about its attributes, about its purposes, and about its outer limits. Almost all our discourse about property has consisted, and still consists, of such claims.

The “property” we talk about now, however, is not the same as the property of 1900, which was not the same as the property of 1800. Our conceptions of property have changed over time, to match the changes in the goals we think are worth pursuing.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!