Nicholas Dungan

Gallatin: America’s Swiss Founding Father

New York University Press

224 pages, 6 x 9 inches

ISBN: 978 0814721117

ISBN: 978 0814721124

Albert Gallatin contributed as fully as any other statesman to the welfare and independence of the young United States, yet he has been largely forgotten by history.

Born in Geneva in 1761, the product of an old and noble family, educated to the highest standards of the Swiss and French-speaking tradition, he immigrated to America at age nineteen and spent almost seven decades thereafter in the service of his adopted country. Gallatin was a politician and diplomat as well as a public intellectual.

His political career included positions as a Pennsylvania legislator, a U.S. Senator, a member of the House of Representatives, and Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Still today, he remains the longest-serving Secretary of the Treasury in U.S. history.

Gallatin then negotiated the end of the War of 1812 with the British, and became U.S. ambassador to France and thereafter to Britain.

At age 70 he moved to New York and undertook a third career. He became president of John Jacob Astor’s bank, a founder and first President of the Council of New York University, President of the New-York Historical Society, an expert in Native American ethnology and linguistics and founder of the American Ethnological Society.

Albert Gallatin’s is the opposite of the stereotypical American immigrant story. Far from arriving destitute and ignorant, he brought the highest standards of civilized Europe to the young America that he went on to serve.

Gallatin made an enormous difference to the course of American history. As Secretary of the Treasury—then the only domestic department of the U.S. Government—he advised President Jefferson on the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States. As negotiator of the Treaty of Ghent, he not only ended the War of 1812 with the British but put the United States on an equal footing with Great Britain for the first time. This is how the United States was able to expand its territory across its own continent and enhance its influence throughout its own hemisphere—during a 19th century in which the sun never set on the British Empire.

Presidents Washington, Adams, Jefferson and Madison all suffered significant historical reverses because of their inability to resist French and British power and interests. Only when the Treaty of Ghent put an end to the War of 1812—thanks to Gallatin’s negotiating skill—did America achieve genuine independence.

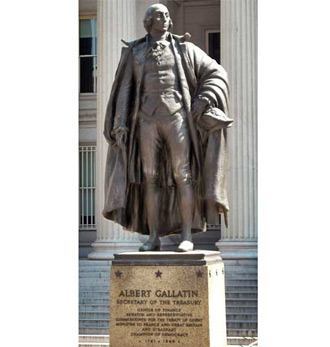

Gallatin’s life demonstrates the value of continental European heritage in American history. His statue stands in front of the United States Treasury building, next to the White House, within eyeshot of the statues of Lafayette, Rochambeau, von Steuben, and Kosciusko. These were the European Founding Fathers of the United States.

Gallatin’s story also demonstrates how much the U.S. was caught up, in the early years of the Republic, in the complexities of European politics and diplomacy—particularly squeezed between France and Britain.

Presidents Washington, Adams, Jefferson and Madison all suffered significant historical reverses because of their inability to resist French and British power and interests. Only when the Treaty of Ghent put an end to the War of 1812—thanks to Gallatin’s negotiating skill—did America achieve genuine independence.

I must have been personally sensitive to this trans-Atlantic significance of Gallatin’s story—I was raised in the United States but spent most of my adult life living in Europe, principally Paris and London, until I returned to the U.S. in 2004.

Shortly after my return to America, I was recruited as president of the French-American Foundation in New York. During the 250th anniversary year of the birth of Lafayette, in 2007, I saw how much of a contribution could be made to French-American relations by celebrating such a symbolic historical milestone. Then, in late 2008, walking past Gallatin’s statue in front of the Treasury set me to wondering whether a similar opportunity for rapprochement and remembrance did not exist for Switzerland.

It turned out that Gallatin’s 250th birthday anniversary would occur on January 29, 2011. So I suggested to the Swiss diplomats I knew that they capitalize on this occasion—and that I write the first new biography of Gallatin to appear in the United States in a generation.

Gallatin’s achievements, including the Louisiana Purchase and the Treaty of Ghent, constitute his practical legacy and are of great import in historical terms. But his life and work resulted also in a philosophical legacy—one that has enduring, indeed contemporary, relevance.

As a politician, Gallatin was consistently an advocate of budgetary responsibility and fiscal discipline. He hated debt—part of his Geneva heritage—and, in his first seven years as Secretary of the Treasury, he paid off nearly half the national debt of the United States.

Both as a legislator and as Secretary of the Treasury, Gallatin consistently took an interest in education and in infrastructure. His interest in education was later evidenced also by his co-founding New York University.

Gallatin believed in government that not only refuses to burden future generations but, in fact, invests for the long-term in people and infrastructure. He sought to make the new country a better place for its future generations—a philosophical legacy of great policy significance in our time.

Another aspect of Gallatin’s philosophical legacy arises from his career in diplomacy: he negotiated in a multi-polar world in which the United States often did not have an advantage over its adversaries. Many of Gallatin’s most successful negotiations resulted from an awareness of the limits of power—also a philosophical legacy of great policy significance in our time.

Although Gallatin participated in creating the circumstances in which America became free to assume its manifest destiny, he privately deplored aspects of the Jacksonian America that such virtually unbridled freedom made possible.

And now, in the 21st century, many thoughtful Americans are wondering whether those Jacksonian values—resolving differences through conflict, assuming that resources are unlimited, pursuing American exceptionalism—are relevant or, indeed, even appropriate to our present and future challenges.

Albert Gallatin, James Earle Frazer, 1947. (AgnosticPreachersKid, Wikimedia Commons.)

I wrote this book for the reader—I wanted the reader to be able to participate in a good story, and for Albert Gallatin to come alive in the pages.

But I was also aware that reading a book—even a book as short, as concise as this one—is a journey that different travelers, different readers, take at their own pace and in their own fashion.

So the Introduction is a roadmap—and yet one with room for surprises and unexpected detours... You can start the book at the beginning of chapter one and not get lost—but if you read the Introduction, you will feel quite sure of where you are throughout the rest of the book.

I begin the Introduction with an abbreviated life of Albert Gallatin, so that you have all the highlights and accomplishments of his life in chronological order, from his birth in Geneva to his death in New York 88 years later—all in less than three pages.

Gallatin’s life and legacy shed a new light on an early America rooted in Europe, an America that was one country among many in a complex world. Only after Gallatin had successfully negotiated the end of the War of 1812 did the United States develop on its own. And by that time the European foundations of the United States had already solidified.

So in the Introduction I lay out the inspiration for this book and examine “The Quandary of Gallatin’s Obscurity”—a haunting question throughout the research and writing.

The Introduction also explains my goal of helping Albert Gallatin’s human story come alive to “a new audience in a new era.” I describe my impressions of who he was, with his strengths and weaknesses, qualities and limitations, successes and failures.

The Introduction ends with a glimpse of the architecture of the book. The nine chapters, organized in three parts, follow Gallatin’s rise, his achievements at the pinnacle of power, and his role as a senior statesmen. But, in a fortuitous pattern, within each of the three parts, there is a similar sequence: he progresses, then has to overcome difficulties, then progresses still further. He does that all three times!

And even covering all this, the Introduction is only six pages long.

Gallatin believed in government that not only refuses to burden future generations but, in fact, invests for the long-term in people and infrastructure. He sought to make the growing country a better place for its future generations.

I will hope that, on both sides of the Atlantic, Gallatin: America’s Swiss Founding Father may serve, at many different levels, to strengthen the sense of shared heritage and shared destiny between the United States and Europe.

My book will prove to have lasting value if it causes the American readers to understand how much they and their country owe to continental Europe. The “Idea that is America” did not appear ex nihilo. The inspiration and the energy that made it possible for the United States to come into being and to succeed thereafter arose from European sources.

One quarter of a millennium after his birth, the Swiss too had largely forgotten Albert Gallatin, and even in Geneva. So I am delighted that my book, and the surrounding Gallatin250 project that I suggested to Swiss diplomacy, have helped revive his memory and increase the focus on his legacy in the land of his birth.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!