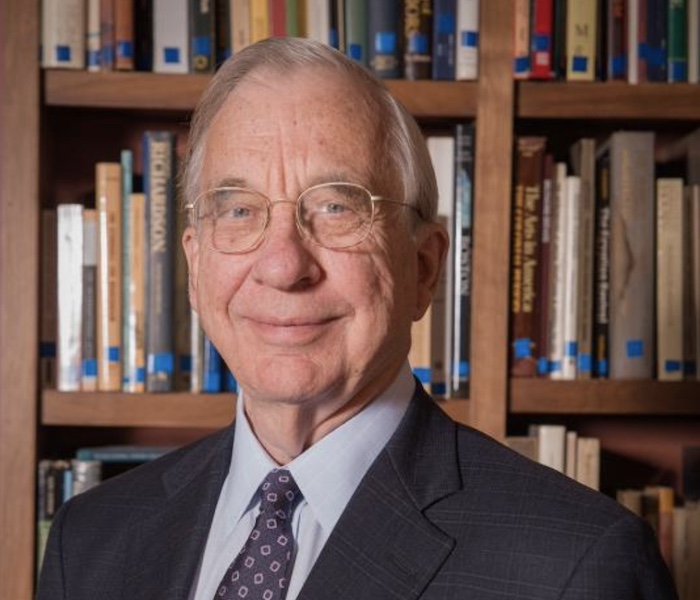

Stephen F. Cohen

The Victims Return: Survivors of the Gulag After Stalin

PublishingWorks

224 pages, 5½ x 8½ inches

ISBN 978 1933002408

The story of survivors of the Jewish Holocaust is widely known. The story of surviving victims of Stalin’s 25-year terror is virtually unknown in the West—and even in Russia itself. The Victims Return tells that story. I focus on a wide array of survivors—including many I knew personally in Moscow in the 1970s and 1980s.

Despite the monstrous crimes recounted in the book, some 50% of Russians surveyed today nonetheless consider Stalin to have been 'a great leader.' I try to explain why this has happened—and what it may mean for Russia’s future. It is not due to Putin’s rule, as the US media regularly asserts.

While I focus on individuals, The Victims Return has a wide angle or broad context.

The book begins with a short overview of Stalin’s mass terror, from 1929 to 1953, and then follows the saga of survivors from their liberation from the Gulag, under Khrushchev in the 1950s, through their attempts to salvage what remained of their shattered professional and personal lives during the years and even decades ahead.

The book also tells the story of what the poet Anna Akhmatova called “the two Russias”—the struggle between the returning victims and the people who had participated in their victimization. Since millions of Soviet citizens were involved on both sides, the book is both political and social history, as well as human saga.

I came upon this little-known story almost by chance—though Russians who knew me said it was my “fate” to write it. And I came upon it not in books or archive documents, but in barely visible realms of Russian life.

Doing scholarly research several months a year in Moscow in the 1970s, I found myself living, through mutual Russian friends, among a large number of Gulag survivors. They, and through them many other terror-era victims, began telling me their stories and especially accounts of their liberation and return to society.

Though it took me thirty years to finally publish the book, I knew even then I had to write it. That’s why The Victims Return, though it also relies on considerable formal research, is substantially autobiographical: I knew personally, and often well, many of the victims I write about. The reviewer for The New Yorker called the book a “memoir”—but it is far from that in the full sense.

Photograph of an NKVD execution squad in 1936. (FromDavid King’s Ordinary Citizens, reproduced in the book on page 45.)

Anna Larina (the widow of Nikolai Bukharin, who was executed in 1938), with their son Yuri, whom she had not seen in nineteen years, and her two younger children, Nadya and Misha, by her second husband, at her place of Siberian exile, 1956. The photographs reproduced on page 50 show Anna Larina’s aging during her years in the Gulag, and Yuri’s in the orphanage.

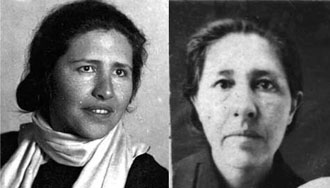

Left, Olga Shatunovskaya before her arrest, in 1936; right, in a Magadan camp, 1945. After her release in the early 1950s, Shatunovskaya became a member of Khrushchev’s inner political circle and, in that capability, helped to free millions of other victims from labor camps and exile.

A 1980 photo of the author with Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko.

I hope that your “browsing reader” glances at the Prologue, the pages one through six. One informed reader said this must be the best short overview of Stalin’s terror ever published.

Having read the horrors described in those few pages may well make one want to know what later happened to the victims that survived them.

In three photo album inserts, I have included striking photos, showing the faces of some names that will be known to more than a few American readers—the widow of Nikolai Bukharin, Anna Larina, and her children—as well as less-well-known others, before, during, and after the years of their victimization.

The faces of the victims need to be seen.

Several compelling photographs of Olga Shatunovskaya are reproduced in the book.

Many of the photos in the book are my own, and thus quite personal.

In the pages eight and nine I explain how this author, who grew up in Kentucky far from all of that, ended up living among Stalin’s victims in Moscow and eventually writing their story. If nothing else, my own “fate” in this regard reminds us how unexpected our lives can be.

The faces of the victims need to be seen.

The Victims Return is about one of the great tragedies of the 20th century and one of its greatest human sagas. But it is also a book about Russia today.

Readers may be surprised to discover that despite the monstrous crimes recounted in the book, some 50% of Russians surveyed today nonetheless consider Stalin to have been “a great leader.”

As a result, yet another debate is underway in Russia over Stalin’s long rule and its present-day relevance—the third controversy since the despot died in 1953 (the first was under Khrushchev, the second under Gorbachev).

In the Epilogue, I try to explain why this has happened—and what it may mean for Russia’s future. And it is not due to Putin’s rule, as the US media regularly asserts. The “significance” of that will be clear to American readers.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!