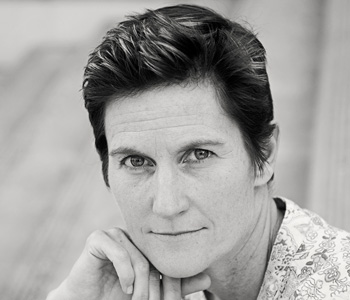

Leigh Eric Schmidt

Heaven’s Bride: The Unprintable Life of Ida C. Craddock, American Mystic, Scholar, Sexologist, Martyr, and Madwoman

Basic Books

350 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0465002986

Heaven’s Bride tells for the first time the story of Ida C. Craddock’s life, death, and afterlife.

A woman “very clever but queer,” as one contemporary described her, Craddock was a late nineteenth-century eccentric—by turns, a secular freethinker, a bookish intellectual, a religious visionary, a civil-liberties advocate, and a psychoanalytic case history. Deemed a grave danger to the public morals for her candor about sexuality, she had six of her marriage reform pamphlets suppressed as obscene literature.

Craddock’s legal problems began when she offered a spirited defense of belly dancing, first introduced to American audiences at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893, and thereafter she was persona non grata to the great vice-crusader Anthony Comstock, the most powerful censor of the day, who saw such performances as abominations. Arrested and tried repeatedly for her blasphemous obscenity, she had become by the end of her life a celebrated martyr among early free-speech activists. Emma Goldman, no stranger herself to iconic status, would later recall Craddock as “one of the bravest champions of women’s emancipation” in an epoch that had many daring campaigners from Victoria Woodhull to Margaret Sanger.

After her death, though, Craddock lived on as mystical madwoman more than lionized liberal, and that reckoning had everything to do with the career trajectory of one of America’s leading civil-liberties lawyers, Theodore Schroeder. He came to know of Craddock’s case through the Free Speech League, an important precursor of the American Civil Liberties Union, but his attraction to her had much more to do with sex (and religion) than with the Constitution. One of America’s most devoted (if not most subtle) Freudians, Schroeder turned Ida C into his own Anna O.

Heaven’s Bride crafts this multilayered story from the reams of manuscripts that Craddock cannily secured, against all odds, from the censor’s fire. “I am poet of the Body and I am poet of the Soul,” Walt Whitman had proclaimed in Leaves of Grass, “The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell are with me.” Craddock, as much as anyone of her era, lived amid those doubled pains and pleasures—as yoga priestess, suppressed sexologist, thwarted scholar, ecstatic mystic, and denounced madwoman.

Craddock’s unmooring from her own Protestant upbringing provides a parable of a larger cultural transformation: the disruption of evangelical Christianity’s power to define the nation’s sexual taboos, artistic limits, and sacred canon.

The retrieval of Craddock’s life from the vaults of vice suppression offers an entryway into major religious, cultural, and political issues of her day—and, often enough, of our own as well.

Foremost among these is the religious and moral character of the United States. No less an authority than the Supreme Court could declare in a decision in 1892 that everywhere in American life there was “a clear recognition of the same truth”: namely, “that this is a Christian nation.” The ideal of a Christian America still holds sway with a significant portion of the American public—but, as a cultural standard, it was first seriously unsettled by religious and secular challenges posed during Craddock’s lifetime.

Craddock’s unmooring from her own Protestant upbringing provides a parable of a larger cultural transformation: the disruption of evangelical Christianity’s power to define the nation’s sexual taboos, artistic limits, and sacred canon.

As Craddock drifted away from her natal Protestant faith, she courted both secular activism and spiritual variety. A leader of the American Secular Union, Craddock pushed that group’s most uncompromising demands for church-state separation, including the purging of prayer and Bible reading from public schools. She also pressed for a universal “sexual enlightenment” on medical, legal, and educational grounds that looked very much apiece with a secular agenda of advancing scientific knowledge against outworn superstition.

Those initiatives, though, were only half her program. Unlike the secular revolutions of sexuality that Alfred Kinsey and Hugh Hefner subsequently tendered, Craddock was part of a larger circle of nineteenth-century marital innovators who imagined a sexual revolution in specifically sacred terms. Seeing no need to blot out all religion, Craddock and her compeers yoked sexual enlightenment to spirituality, the marriage bed to the passions of mystical experience.

That maneuver, however baffling it sounded to secular liberals, carried a silver lining for them in their opposition to Christian statecraft and moral crusading: Sex, like religion, was made an intimate affair of personal satisfaction and individual liberty, a private matter of the heart. Human sexuality, once redeemed by spiritual association, could shed the veil of censorship and don the halo of free expression.

Craddock also had to negotiate her way through a rapidly changing intellectual landscape. At once scholar and seeker, she occupied an ambiguous position amid a series of newly demarcated fields of inquiry, including comparative religions, psychology, folklore, and sexology.

Unlike William James at Harvard, Morris Jastrow at the University of Pennsylvania, or G. Stanley Hall at Clark University, Craddock never inhabited an ivory tower that raised her to the level of reputable academic observer. Instead, as a love-steeped mystic, adrift and exposed, she herself became the object of scientific scrutiny.

A skilled shape-shifter, Craddock always remained hard to pin down as a specimen, but that elusiveness seemed only to intensify the desire to categorize her. Was she merely one more case history who could be pigeonholed by the new psychological and neurological sciences—an erotomaniac, nymphomaniac, or hysteric, a victim of an insane delusion of one diagnostic type or another? Or, was she a latter-day visionary, a weirdly American Teresa of Avila, “the madwoman,” as Hélène Cixous put it, “who knew more than all the men”?

The scales were inevitably weighted against her. She would lobby hard, and unsuccessfully, to open the liberal arts at the University of Pennsylvania to women. Thanks, in part, to that early frustration of her collegiate ambitions, Craddock had to make her way as an untethered amateur in a world increasingly controlled by professionals and specialists.

Kept on the intellectual margins, Craddock often delighted in her own unconventionality, well aware that her very extremity allowed her to dramatize one cultural struggle after another: How much muscle would evangelical Protestantism have to define and enforce the norms of American literary, sexual, and religious expression? Would women be able to claim academic standing, spiritual authority, and social equality in American public life? Was visionary experience an empowering capacity or a debilitating clinical symptom? Was the erotic redeemable, a grace rather than a curse, a spiritual yearning as much an animal appetite? Those large questions are the durable refrains of Craddock’s story.

If a reader were just dipping into the book, I hope that he or she might first browse the fourth chapter.

Against all odds, Craddock went about her work as a marital advisor and sex expert. She recorded notes on those she counseled, and these cases offer a startlingly frank and often painful look into the distress of her clients. Here is an example:

Eunice Parsons, a young nurse newly engaged in the summer of 1902, was worried about her fiancé, a piano-tuner, and had sought out Craddock for a lesson on married sexual relations. The couple had recently had “some frank talks,” and it turned out her betrothed, “a very pure-minded man,” was of the opinion that “people should have intercourse only for childbearing.” Parsons, taken aback, objected, “Suppose I don’t want any children; what then? Are we never to have intercourse?” As their discussion turned into a quarrel, her intended life-partner reproached her for being too passionate, and now she wondered if their apparent sexual incompatibility made it necessary for them to call off the wedding.

“I have made up my mind never to marry any man until he can look at the sex relation as a pure act and a sacred act,” Eunice vowed. Her would-be husband, however prudish he sounded, held the stronger hand in this dispute: Most marital advice literature of the period, religious or not, refused to disjoin the pleasure of sex from the purpose of procreation and would have seen this particular stand-off as a worrying reversal of the usual relation of male desire and female modesty. Parsons, fortified by Craddock’s teachings, nonetheless pressed her fiancé to reconsider his views and even convinced him to go in for a lesson himself.

Meeting with Craddock could not have been comfortable for the young man, a resolute virgin. For her pedagogy to be effective, Craddock thought it essential to explore the sexual history of her clients with a battery of diagnostic questions, including blunt inquiries about masturbation (yes, he had done that “to some extent when a boy”) and erotic dreams (yes, he had experienced a few).

The piano-tuner tried to shift the tenor of the exchange through religious argument and scriptural citation: “Quoted the Bible very earnestly,” Craddock wrote in her case notes, “about there being a war between the spirit and the flesh, to prove his contention that coition should take place only for child-bearing; say once every few years; . . . marriage was intended for the replenishment of the earth.”

Unfortunately for him, Craddock wanted nothing more than to have their sex-talk turn spiritual, and soon she was explaining how in her understanding of the divine “God was feminine as well as masculine.” “I told him to think of his wife’s yoni as containing a chapel, into which he was to enter to worship—not worship the woman, but worship God,” Craddock instructed. That lesson left him red-faced; he kept sputtering “his one idea of no coition except for child-bearing” and even insisted that his fiancée’s physical affections were supposed to be purely maternal in expression. Eunice need only dote on their prospective children, not satisfy (let alone incite) his sexual desires. “Well, well,” Craddock concluded, “if he doesn’t manage to rid himself of his idée fixe, he’ll find himself minus his sweetheart before long.”

Only at the insistence of his betrothed did the piano-tuner return for three more lessons. He bristled at his fiancée’s newly acquired “independence of thought and action” in pushing him into this disagreeable situation, but criticizing a woman for “thinking for herself” was a non-starter with Craddock who greeted this male presumption only with barbs. Forced quickly into retreat on that point, he found himself losing ground on the main argument as well, finally acknowledging that sex for non-procreative purposes could be “pure and holy and perhaps ‘normal’ after all.”

By the close of the fourth session Craddock had gone a long way toward saving the engagement. If the piano-tuner remained wary of Eunice’s alliance with Ida, he at least had begun displaying a new appreciation for his lover’s sexual appetites and was ready to reconsider his own religious asceticism.

A skilled shape-shifter, Craddock always remained hard to pin down as a specimen, but that elusiveness seemed only to intensify the desire to categorize her. Was she merely one more case history who could be pigeonholed by the new psychological and neurological sciences—an erotomaniac, nymphomaniac, or hysteric, a victim of an insane delusion of one diagnostic type or another? Or, was she a latter-day visionary, a weirdly American Teresa of Avila, 'the madwoman,' as Helene Cixous put it, 'who knew more than all the men'?

The advent of a secular sex revolution would render the spiritual sex revolution of nineteenth-century reformers like Craddock an increasingly bygone inheritance. “No Gods, No Masters” had been Margaret Sanger’s slogan for the Woman Rebel, and a substantial portion of the twentieth-century movement for sexual emancipation would march forward under such secular banners.

In 1979, when one of Craddock’s long suppressed pamphlets was finally republished, the reviewer for the New York Times tellingly remarked: “If one excised from Ida C. Craddock’s widely banned ‘Right Marital Living’ its pious obeisance to religion, the plain and mostly accurate talk about orgasm and the ‘marital embrace’ would fit easily into a contemporary sex manual.”

Craddock’s cultural world—one in which metaphysical speculators and spiritual drifters were in the front ranks on sex-reform and civil-liberty causes—now sounded unimaginably foreign. If Craddock were to tally with the post-Kinsey, Masters and Johnson era of scientific sexology, her religion would need to be pared away.

Not that sex had been successfully secularized by 1979. This was the very year, after all, in which Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority, appearing, to the political left, poised to become the new Anthony Comstock. (And if not Falwell, then Donald Wildmon, who had two years earlier founded the National Federation for Decency, with its strong anti-obscenity agenda.)

With the rise of the Moral Majority and allied organizations, secular liberals were hard-pressed to envisage any form of religious piety as the handmaiden of sexual emancipation. Strict constructions of church-state separation and personal privacy—“Get Your Bible Off My Body” and “Focus on Your Own Damn Family”—seemed, once again, imperative for the protection of a liberal civil society.

In appealing to both secular principle and religious vision, the social reformers who had championed the companionate equality of marriage partners, the importance of female passion and sexual pleasure, the liberalization of divorce laws, and the rights of reproductive control, had now become ghostly anomalies. But Craddock and other “disreputables” had much to say about the joined privacy of religion and sex.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!