Berenson, Edward

Heroes of Empire: Five Charismatic Men and the Conquest of Africa

University of California Press

370 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0520234277

Heroes of Empire tells the story of five colonial figures, two British and three French, who made imperial conquest exciting, even exhilarating, for millions of ordinary citizens.

Most British and French people never set foot in their country’s imperial possessions, nor did they have any economic interests there. But between 1870 and 1914, imperialism became a hugely popular phenomenon. The press gave it top billing, advertisers embraced its “exotic” imagery, and above all, people looked up to the charismatic heroes whose adventures seemed to turn overseas expansion as a series of extraordinary, personal quests.

The heroes in question include Henry Morton Stanley, famous for uttering, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” and infamous for his ruthless Congolese exploits; Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, the “pacific conqueror” who has admirers in Africa to this day; Charles (Chinese) Gordon, one of four “Eminent Victorians” that the Bloomsbury writer Lytton Strachey saw as archetypes of the age; Hubert Lyautey, the dashing soldier-scholar who conquered Morocco for France; and Jean-Baptiste Marchand, the French “hero of Fashoda” whose band of 150 men briefly stood up to an Anglo-Egyptian army 25,000 strong.

Ordinary British and French men and women remained indifferent to empire. But that disinterest did not extend to those who braved the scarcely imaginable dangers of unknown places and 'savage' people. Ordinary citizens concentrated on heroes.

There are two main contexts for this book, the first of which has to do with Barack Obama and charisma.

I began work on this book when the then junior senator burst onto the political scene. This inexperienced politician, a young man just two years into an uneventful Senate career, seemed to pack a political punch unrelated to any institutional power or recognized accomplishments. His political oomph appeared to come from out of nowhere, though many associated it with his apparently dazzling personality.

Obama immediately caught the media’s attention, and on TV in particular, he appeared to posses that indefinable something, that “it,” identified by the great German sociologist Max Weber as “charisma.”

Charisma, Weber wrote, was a kind of gift, an inexplicable force that makes those who possess it different from other people, magical in a way, and all the more powerful for the impossibility of putting one’s finger on its source.

Obama rode to the presidency partly on the strength of his charismatic aura, and a great many of his followers attributed near magical abilities to him. Once in the White House, he would quickly turn the country around—or so some of Obama’s supporters thought.

Even without the economic crisis, the new president would inevitably have disappointed his most ardent followers—and the journalists and media figures once smitten as well. When the reality hit hard, media and public alike abandoned Obama as suddenly as they had embraced him two years earlier. His charisma drained away, just as Weber would have predicted. The sociologist wrote that charismatic authority is fragile; to persist, it needs constant validation from supporters.

The President’s seesaw of adulation and condemnation helps explain the so-called “enthusiasm gap” between disillusioned Democrats and highly charged Republicans. The latter have been stirred by a charismatic Tea Party movement and leaders like Sarah Palin, who suddenly enjoy considerable influence and power. Palin’s authority resides in the media-enhanced aura that surrounds her, rather than political achievement and experience.

As I began to write about European explorers and conquerors of Africa, it occurred to me that they too possessed charismatic power, the ability to attract legions of followers and wield enormous political influence—without necessarily accomplishing anything of note.

Henry Morton Stanley didn’t actually “find” Livingstone—who was never really lost. And Stanley’s final African journey, the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, proved an abject failure. Emin, like Livingstone before him, refused to be “rescued.” In both cases Stanley’s expeditions needlessly cost hundreds of African and European lives.

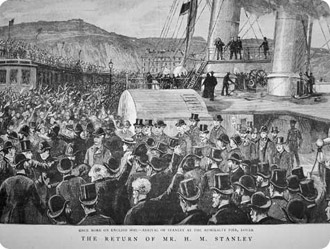

But none of that mattered at the time. Stanley returned from the Emin Pasha expedition the most famous man in England. The public acclaim surrounding him was such that even the British prime minister had to take seriously what Stanley said. Queen Victoria, meanwhile, decided to make Stanley a knight.

The other context for Heroes of Empire is historiographical.

Historians of empire have traditionally argued that the majority of people in Britain and France took little interest in the details of overseas expansion—the geographical boundaries in question, the supposed economic advantages, the putative political gains, the strategic objectives involved.

This view is surely correct. But it doesn’t follow, as historians once thought—although less so nowadays—that the lion’s share of British and French men and women remained indifferent to empire.

The broad public in both countries may have been disinterested in the politics and economics of imperialism, even scorning them at times. That disinterest did not extend to those who braved the scarcely imaginable dangers of unknown places and “savage” people, who revealed traits of character and personality widely admired in each society.

The political leaders and administrators, who constituted what the historians Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher called the “official mind” of imperialism, may have focused on policy. But ordinary citizens concentrated on heroes.

An image from the Illustrated London News, 3 May 1890.

My hope is that the book’s opening paragraph will do what a lead paragraph is supposed to do: make browsers want to read on.

I open with the young French army captain, Marchand, tugging a dismantled steamboat across the forbidding, malarial landscape of Central Africa. He is en route to Fashoda, a “wretched” no-man’s-land on the Upper Nile.

For reasons nearly unfathomable today, Fashoda loomed large in the 1890s as a strategic imperial key to the entire African continent. Marchand never stood a chance of preventing the powerful, mechanized Anglo-Egyptian army from taking Fashoda. But the Frenchman’s stubborn effort to claim the broken-down fort made him his country’s most celebrated fin-de-siécle hero.

Marchand was said to embody the best of what it meant to be French. How and why the captain’s hopeless cause and subsequent “glorious defeat” made him so popular is what my book is all about.

It isn’t every day that an independent African state pays homage to the European who had once subjected its people to colonial rule. But Congo’s rulers are so unpopular and Brazza’s reputation as a humane leader so durable that the Congolese government wanted to bask in the aura that still surrounds the explorer’s name.

I don’t think history needs to be “relevant” to our contemporary concerns, but if it is, so much the better.

Heroes of Empire shows how the mass media personalizes major events and phenomena and often makes one individual stand in for large and complex social, political, and/or cultural forces.

Doing so oversimplifies the forces in question and exaggerates the power and import of the individual or individuals in question.

In the late 19th century, the French penny press often made the explorer and “pacific conqueror” Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza the embodiment of its so-called “civilizing mission,” its putative effort to improve the lives of colonized peoples. Nowadays, media outlets often make Sarah Palin or Sharon Angle synonymous with the Tea Party—thus erasing much of its complexity, diversity, and political independence. In the wake of 9/11, journalists all too commonly distilled the world’s disparate radical Islamic movements into the person of Osama Bin Laden.

In the epilogue to my book, I turn to the important issue of historical memory, to the question of why we remember certain individuals and events and not others. Naturally, I use as examples the five charismatic figures around whom I organized the book.

Very few people nowadays remember Chinese Gordon, Jean-Baptiste Marchand and Hubert Lyautey. Gordon belongs to a Victorian era for which little more than a pinch of nostalgia remains. Marchand might have remained famous had Britain and France gone to war over Fashoda, as they nearly did. But when the two countries became allies in 1914 and again in 1944, the old colonial animosities of the nineteenth century largely withered away. As for Lyautey, who conquered and ruled Morocco between 1904 and 1925, his memory vanished in France’s bloody Algerian War of 1954-62. The horrors of that conflict diverted attention away from France’s other North African territories, Morocco and Tunisia.

While Gordon, Marchand and Lyautey have largely disappeared from view, both Stanley and Brazza have retained our attention.

Almost everyone knows Stanley’s absurdly laconic greeting, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Popular writers and biographers continue to focus attention on him. Adam Hochschild made Stanley the number 2 villain of his excellent and widely read book about the evils of Belgian colonialism, King Leopold’s Ghost (1998). Jim Jeal’s revisionist biography of the explorer (2007) has evoked a great deal of comment and controversy over the past couple of years. So have the photographer Guy Tillim’s celebrated pictures of a toppled Stanley statue lying facedown in an abandoned Kinshasa lot.

As for Brazza, his memory returned to the news in 2006 when the Republic of Congo (aka Congo-Brazzaville) erected a $10 million memorial to the French explorer and founder of France’s colony there.

It isn’t every day that an independent African state pays homage to the European who had once subjected its people to colonial rule. But Congo’s rulers are so unpopular and Brazza’s reputation as a humane leader so durable that the Congolese government wanted to bask in the aura that still surrounds the explorer’s name.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!