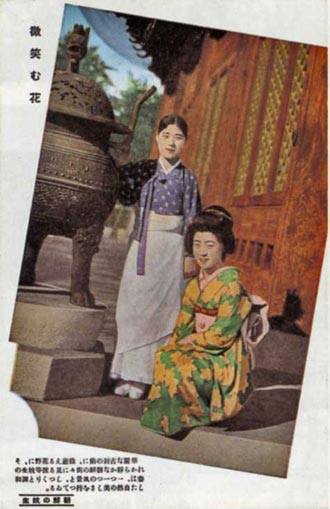

Primitive Selves offers a different take on the history of Japanese colonial rule in Korea. Whereas most studies focus on specific policies—such as economic exploitation, compulsory education, assimilation directives, military mobilization, mechanisms of social control, and suppression of nationalist resistance—designed to erase indicators of an independent Korean national identity, this book examines this imperial relationship from the perspective of culture.I argue that, alongside the brutality of Japanese colonialism in Korea, there was a parallel—if contradictory—impulse to document, preserve, and exhibit selected aspects of Korean folkloric culture and performance art.I contend that the attraction many Japanese felt toward Koreana was an expression of an anti-modern ambivalence, a nostalgic longing for a primordial, elemental lifestyle abandoned in the rush to modernize.Because colonial ideology and ethnological science posited the ancient ethnic kinship of the two peoples, for Japanese, gazing on Koreans was like looking in a mirror through a time warp.The Japanese gaze on Koreana, moreover, transformed Koreans’ sense of the importance of their own cultural traits and expressive forms, rendering them into emblems of nationality worthy of official recognition by the post-liberation Korean states.Individual chapters make these points by focusing on Japanese verbal and photographic ethnographies of Koreans, official curatorial endeavors to preserve and display Koreana, and the prevalence of Korean music, dance, and kisaeng iconography in imperial Japanese mass media culture (which prefigured the “K-Wave” of early 21st century).While it is certainly not my intent to “correct” the narrative of Japanese cruelty in colonial Korea, I do present abundant evidence that prominent Japanese were entranced by Korean arts and culture. This fascination indicates a degree of self-reflection—even self-loathing—among Japanese who were not so enchanted with their own modernity.