Paula Lupkin

Manhood Factories: YMCA Architecture and the Making of Modern Urban Culture

University of Minnesota Press

312 pages, 10 3/4 x 8 1/2 inches

ISBN 978 0816648351

ISBN 978 0816648344

Although it engages directly with the fields of architectural history, gender studies, and urban history this book is really for anyone who has ever gone swimming, or played a game of pick-up basketball, or worked out at a YMCA.

It is also for anyone who has walked on by the local YMCA without taking much notice of the building. In other words, it is really for everyone: a call for understanding the role of architecture in shaping our everyday lives.

My goal in writing Manhood Factories was to draw attention to the meaning and importance of urban buildings we all take for granted. Manhood Factories invites people to pay attention to seemingly unremarkable structures, like the YMCA. The unassuming facades of these buildings masked the organization’s program to mold a modern, corporate, yet moral urban society through recreation and leisure.

The history of architecture is more broadly significant if we study the warp and the weft, the big monuments and small buildings together, as the urban fabric of the city.

The American Young Men’s Christian Association, which began as a Protestant evangelical voluntary association in the 1850s, built hundreds of buildings in the years between the Civil War and the Great Depression. These YMCA buildings were more than a place for young men to play; they were a successful attempt to infuse traditional Protestant values of hard work and self-restraint into an environment that was increasingly defined by an ethic of consumption and the rise of corporate culture.

Y buildings were our first community centers. Before the YMCA started to construct clubhouses, there were few respectable public places to spend the increasingly structured “leisure” time available to urbanites. This religious group legitimized and rationalized leisure, providing an alternative to the saloon and the theater that was to influence dozens of other private and public agencies, including the YWCA, the settlement houses, and municipal reform groups.

The processes by which YMCA buildings were made and used articulated complex ideas about religion, gender, race, and class. Manhood Factories traces the evolution of Y buildings from “Christian clubhouse” in the 1870s to hotel and community center in the 1920s, focusing on fundraising, design, construction, programming, marketing, and use. These activities shaped not only the lives of YMCA members, but also the larger public culture and public space of the modern American city.

Manhood Factories is the first book to take YMCA architecture as its subject and its scope is large. This is not the story of a few key buildings, but an account of a national and even international movement.

It was in many ways the size of the enterprise that attracted me to the project. Why, and how, did the YMCA build so much? How did the YMCA become a building? And why did they all look alike?

Traditionally, scholars of the built environment have enforced a strict hierarchy of high and low. In architectural history, the field in which I was trained, the subjects of study are exemplary, even extraordinary buildings designed by famous architects. There are a few Y buildings designed by big names, but I was interested in the phenomenon as a whole, rather than the greatest hits. Vernacular architecture studies focus on common buildings with no named designer, but typically these are rural barns and houses. Manhood Factories addresses the space in between; what I call the middle ground.

Neither high nor low, the middle ground is the common landscape of American cities. Middle ground buildings are usually designed by architects, but they aren’t famous ones. The appearance of middle ground buildings isn’t distinctive; in fact it is often standardized and indistinguishable from one example to the next. They are often seen as the background to the great monuments that have been the object of study.

Manhood Factories was my opportunity to put buildings like the YMCA, present in every town in nearly identical form, in the foreground. Following in the path of vernacular architecture studies, my claim is that every YMCA building in every town is interesting and can tell us something about the people that made and used it.

The story of the Y suggests that the history of architecture is more broadly significant if we study the warp and the weft, the big monuments and small buildings together, as the urban fabric of the city.

Focusing on the processes that, in the words of sociologist Henri Lefebvre, produce space, my “middle ground” approach to the study of YMCA buildings addresses traditional art historical issues of style and precedent, but also places tremendous importance on the social, economic, political, and religious systems that gave rise to a national building movement.

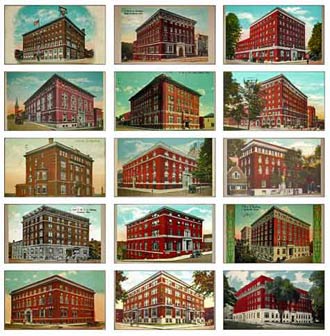

A selection of postcards from the Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection depicting buildings designed by specialist architects Shattuck and Hussey, 1904-1916.

One of the most intriguing visual elements of Manhood Factories is the extensive reproduction of postcards from the more than 10,000 items preserved in the Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection at Springfield College.

Postcards are perhaps the richest source I encountered in my research because they offer so many layers of information. From a purely documentary standpoint, they serve as record of the appearance of Y buildings. Too often these buildings have been demolished and postcards are a quick and accessible snapshot of a building’s form and immediate context. Taken together, they provide a catalog of YMCA buildings that is unmatched in its completeness.

The importance of these postcards, however, goes far beyond simple documentation. Placed side by side, as they are arranged in the book, the postcards highlight the impact of standardization on the organization’s architectural identity. Seeing building after building in the same size and same style really drives home the idea of the YMCA as a building “type” that helped to define Main Street America.

First introduced in the late nineteenth century and legalized by the postal service in 1901, correspondence cards with images printed on one side were a national craze in the first two decades of the twentieth century. They were a quick, cheap, and easy way to communicate in an age of fast mail service and still incomplete telephone systems. Billions were sold each year, and special postcard shops opened to meet demand.

These little 3 x 5 cards, with image on one side, and often, with writing, dates, and addresses on the other, also have value as a source of information about the diffusion and reception of the YMCA building across the United States. They are really unparalleled sources in their capacity to reveal how people learned about the YMCA, and how they understood its buildings.

YMCAs and local boosters printed cards as a symbol of pride, and they were sent all around the country as proof of the community’s progressive and moral character. Pen pals exchanged views of YMCA buildings in their cities, traveling salesmen and young men sent home reassuring cards from the YMCA to their wives and mothers, who collected them into albums or displayed them on the mantelpiece. The choice of a YMCA card had particular meaning for these correspondents, a fact made clear in many of the messages that were written on the verso side.

In this study, which is heavily drawn from materials published by the YMCA itself, the exchange of postcards offered refreshing and necessary insight into the popular reception of the YMCA. It helped to explain how and why the idea of the YMCA building, invented by New Yorkers, found traction and acceptance throughout the rest of the country. New technologies, like cheap color printing and railroad mail service, made it possible for everyday people to learn about the YMCA, to interpret it to their friends, and, through comparison to other cities, to come to understand the role of its buildings in the modern development of their hometown. Through the collection and distribution of postcards ordinary people gained agency in making these buildings meaningful, and I was thrilled to be able to include them in the book.

Pen pals exchanged views of YMCA buildings in their cities, traveling salesmen and young men sent home reassuring cards from the YMCA to their wives and mothers, who collected them into albums or displayed them on mantelpieces.

Manhood Factories is not simply a study of the place where young men played basketball. I wanted to account for how Americans negotiated the social, economic, and spatial transformations modernity wrought upon the American city.

The book contributes to gender studies by providing a badly-needed history of masculine space. It also sheds light on the role of religion in the rise of corporate culture, east-west technology transfer in the early twentieth century, the cultural dynamic between metropolitan and provincial centers in Gilded Age America, and the rationalization of leisure in the age of efficiency and productivity.

Most of all the book demonstrates the importance of the built environment in our broader understanding of American history. Usually relegated to a relatively obscure position as a subfield of art history, the history of building, and buildings, has broader significance.

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!