Lynn M. Morgan

Icons of Life: A Cultural History of Human Embryos

University of California Press

328 pages, 9 x 6 inches

ISBN 978 0520260443

ISBN 978 0520260436

Icons of Life explains how we came to think of embryos as tiny, unborn versions of our selves.

Today embryos and fetuses are veritable little persons; they star in their own videos, are featured in magazines, provide employment, and prompt legislation. How did they become such animated, lifelike, volitional little things?

There was a time, not long ago, when even well-educated adults would hardly have been able to imagine what a human embryo looked like. And they certainly did not grant embryos or fetuses much moral or political status.

In this book, I argue that our embryological world view is not based simply on an accumulation of facts, but on a rendition of those facts that portrays embryos as independent entities—and that masks the way in which fetal images are produced.

Icons of Life describes a little-known embryo collecting project funded by the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1913.

Anatomists based at Johns Hopkins began to collect embryos and to encourage their colleagues to save the contents of the uterus when their pregnant patients miscarried, aborted, or died. Early pregnancy testing did not yet exist, so some of the youngest specimens in the collection came from elective hysterectomies deliberately timed to coincide with the earliest stages of an undiagnosed pregnancy. By 1944, the Carnegie Human Embryo Collection had grown to nearly 10,000 specimens.

Scientists’ descriptions of those specimens shaped much of what we now know about embryological development.

Ironically, those specimens came to symbolize the beginnings of human life. Yet even many of today’s iconic images of embryonic and fetal “life” actually depict dead specimens.

Meanwhile, until now, the strange story of human embryo collecting has remained largely hidden.

Even many of today’s iconic images of embryonic and fetal 'life' actually depict dead specimens.

It was a beautiful day in June on the campus of Mount Holyoke College. I had planned to go strawberry picking, but I found myself instead in the basement of the biology building looking at row after row of dead fetuses. I counted 87 formalin-filled jars of decrepit human fetal specimens, long neglected on a storeroom shelf. I left the building a bit dazed, but I wanted to learn how and why so many human specimens had found their way to those shelves, next to the fetal pigs and pickled snake. Later I learned that Wilhelm His, the famous 19th century German embryologist, had often referred to human embryos as “the fruit.”

The Mount Holyoke collection was a link between the past—when embryo specimens were prized scientific objects—and the present, when encounters with dead fetal specimens are regarded as distasteful and macabre. I later learned that Mount Holyoke’s fetal collection was a small outpost of widespread embryo collecting projects popular among American anatomists, zoologists, and doctors from the 1910s to the 1940s.

This vast collecting enterprise has now been largely forgotten, yet it is relevant to contemporary debates because it shows that embryological knowledge has always been steeped in social meaning. Embryologists studied embryo morphology in exacting detail, but the knowledge they produced was heavily inflected by non-embryological controversies.

The book discusses a few examples. Embryos were featured during the Scopes trial in the 1920s, when the embryo’s “caudal appendage”—otherwise known as its tail—was described in the popular press to prove the similarity between humans and monkeys. Western anatomists gathered hundreds of fetuses in China in the late 1910s, in hopes of finding racial differences embodied in embryological development. When early 20th century embryologists spoke publicly about the embryos, they spoke not about abortion or contraception—topics that were considered largely irrelevant to embryology—but about the biological basis of race, the doctrine of prenatal impressions, and the theory of evolution.

Like people everywhere, the participants in these controversies projected their cultural and historical concerns onto their understandings of embryonic life. In other words, they saw what they wanted to see. Icons of Life argues that there is not a pre-social or purely scientific way to “know” embryos: cultural understandings of embryos always reflect social concerns.

Early 20th century embryologists were confident they had the right to collect thousands of miscarried human embryos for scientific study—even if that meant performing a hysterectomy on a pregnant woman. Their cavalier attitude may seem disturbing or illegal today—our discomfort just shows how drastically embryo meanings have changed over time.

Nowadays, embryos and fetuses are everywhere, but dead specimens have fallen out of fashion. They’re too macabre. They have been replaced by glamorous, computer-enhanced embryonic and fetal figures beckoning to us from plasma flat screens and sumptuous coffee-table books. Few of us would imagine that these images are sometimes produced using the exact same decades-old specimens from the Carnegie Human Embryo Collection.

It isn’t easy to “read” these images as either pro-life or pro-choice, because contemporary embryos and fetuses perform complex political work, functioning often simultaneously as education, entertainment, art, and propaganda.

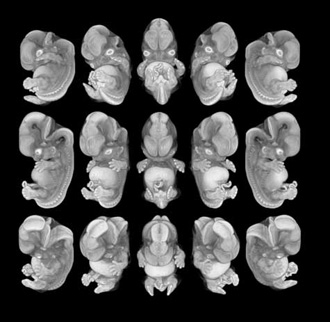

Magnetic resonance image of a 50-day human embryo. (Courtesy of Bradley R. Smith, School of Art and Design, University of Michigan.)

The first time I visited Carnegie embryo collection, I had just finished reading Bobbie Ann Mason’s 1993 novel, Feather Crowns. Mason tells the story of a hardworking farm wife named Christianna Wheeler, who gave birth to quintuplets in rural Kentucky in 1900. Strangers descended on the homestead to gawk at the tiny babies, who succumbed one by one to fever, insufficient milk, opium-laced soothing syrup, and “being handled too much.”

The undertaker convinced the grieving Wheelers to have the bodies embalmed and sealed in a glass case. Several months later the Wheelers, broke and desperate for cash, agreed to accompany the corpses on a carnival tour. They traveled through the South, enduring the stares of coldhearted curiosity seekers who paid a dime to witness their misfortune. One night, the Wheelers stole away and boarded a train to Washington, where they donated the quints’ bodies to the Institute of Man, which kept, in Mason’s words, “a restricted collection, for research students and medical specialists.”

I had just finished the book, and with the Wheelers’ ordeal fresh in my mind I walked into the National Museum of Health and Medicine in the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. The embryos were not on public display, so I was escorted upstairs while I pondered how much space they must need to house 10,000-plus jars of formaldehyde. Imagine my confusion, then, when my guide ushered me into a large windowless room and pointed across rows of filing cabinets. “Here,” she said, “is the collection.”

The embryo collection consisted not of whole, wet-tissue specimens as I had imagined, but of sectioned specimens. Each embryo had been painstakingly cut into thin slices, or sections, each of which was stained and mounted on a slide for viewing through a microscope. The filing cabinets were filled with small wooden boxes, each containing several glass slides. “Here are the saggitals, over here we have the coronals, and these are the transverse sections,” my guide explained.

Because I was not trained as an anatomist, I struggled to keep up with the unfamiliar terminology. She pointed out a separate aisle of “comparative” (that is, non-human) embryo specimens, including guinea pigs, macaques, and opossums. The embryologists may have found it easy, as one of them said in 1918, to see “life in a dead section,” but I did not. I found all the information disorienting, especially in that windowless room after a late night of reading, and by lunchtime I was looking forward to a break.

I had lunch with two anatomical curators for the museum. They asked about my project, and we talked about attitudes toward miscarriage and infant death in the late 19th century. As I urged them to read Feather Crowns and gave a quick plot summary, I saw them exchange a knowing glance across the table.

“Would you like to see the quints?” one of them asked.

It turned out that Mason had been inspired to write Feather Crowns by an actual event that took place not far from where she grew up. On April 29, 1896, five boys—named Matthew, Mark, Luke, John and Paul—were born to Mrs. Elizabeth Lyon in Mayfield, Kentucky. The “Mayfield quints,” as they were known, did not live long; the smallest one died on May 4 and the last one just ten days later. Their mother told a reporter, “My babies were all fully developed, but they just starved to death—that and the crowd. You never saw the like of the people.”

The real Elizabeth Lyon had indeed taken the embalmed bodies on a carnival tour, but instead of running off to Washington she had taken the quints’ corpses home to Kentucky, where no one could blame her for becoming a bit unhinged. She reportedly stored them in the barn and under her bed until, old and destitute, she sold them to the Army Medical Museum for considerably less than the asking price. They were on display for several years but have now been retired to a drawer, just downstairs from the dead embryos.

There is not a pre-social or purely scientific way to 'know' embryos: cultural understandings of embryos always reflect social concerns.

The Carnegie Human Embryo Collection was designed to provide basic descriptive information about human gestational development at a time when most Americans hardly knew what embryos looked like.

The embryo collectors changed all that. With their plaster models, scientific articles, and museum exhibits, the information they produced taught us to see in embryos an image of “ourselves unborn.”

And we accepted it, because we have a cultural penchant for imbuing biological events with social significance. The embryo collectors helped to solidify the biologically based origin story we tell ourselves about how we come to be.

It was an embryo-production project—an intensely gendered, often patronizing, and sometimes colonialist project that separated women’s lives, bodies, and futures from the embryo and fetal subjects that appear so independent today.

Human development is now construed as a natural process about the “facts of life,” rather than as the historical outcome of a scientific project to produce embryos and cast them as biological entities, while rendering pregnant women virtually invisible.

As new constituencies claim the right to tell conflicting stories about embryos, Icons of Life poses the question: how do we know what embryos mean?

The cultural history of embryo collecting helps to explain who authored the seemingly self-standing embryos that reside at the center of so many contemporary debates.

.jpg)

We don't put paywalls. We don't distract you with ads. We don't sell your data.

Please help to keep this running!