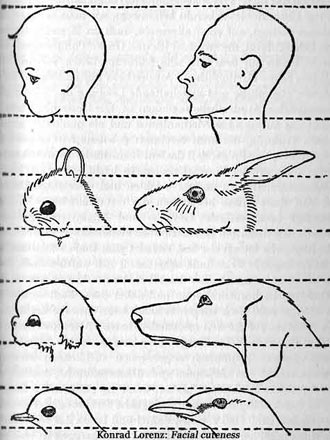

Supernormal Stimuli explains how our once-helpful instincts get hijacked in our garish modern world. Instincts for food, sex, or territorial protection evolved for life on the savannahs 10,000 years ago—not today’s world of densely populated cities, technological innovations, and pollution.Nobel Prize-winning ethologist Niko Tinbergen biologists coined the term “supernormal stimuli” in the 1940s to describe imitations that appeal to primitive instincts and exert a stronger pull than the real thing. In his experiments, song birds abandon their pale blue eggs dappled with gray to hop on black polka-dot Day-Glo blue plaster eggs so large they constantly slide off and have to hop back on.Tinbergen and his students eventually constructed supernormal stimuli for all basic animal instincts—comically unrealistic dummies which an animal will try to mate with or fight with in preference to a real individual if color, shape or markings push their buttons.These behaviors look funny to us... or sad—the reflexive instincts of “dumb” animals. But then there’s a jolt of recognition: just how different are they from our behavior? In Supernormal Stimuli, I apply this concept to explain most areas of modern human woe.Animals encounter supernormal stimuli mostly when an experimenter builds them. We make our own, from candy to pornography, from stuffed animals to atomic bombs. We’ve reversed the relationship between instinct and object to manufacture a glut of things which gratify our basic desires with often-dangerous results.The “good news” in this is that the concept of supernormal stimuli itself—this image of the bird on the day-glo blue egg—can help us realize where we’re going wrong and help our huge brains to kick in and exercise self-control.We need to “trust our instincts” less and trust our intellect more. Recognizing a supernormal stimulus when we see one is the most important step.

.png)